Inflationary pressures, increased tax rates on profit extraction and an overall tax burden taking us back to 1950.

As the dust settles on the government’s decision to increase NICs from April next year – and its conversion into the health and social care levy from 2023 – it is helpful to reflect on the wider implications for business and the tax system.

It is also important to consider the impact of this tax rise alongside the already announced increase in corporation tax to 25% from April 2023, the outlook for UK tax policy more generally and wider economic factors.

Specifically, the NIC increase has implications for:

Profit extraction from companies: Both the corporation tax increase announced in March, and higher NIC, up the overall tax rate on profits earned in a company and then extracted by the owner.

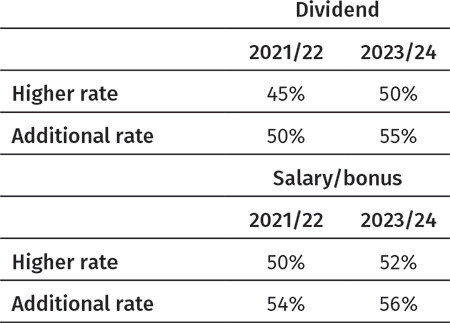

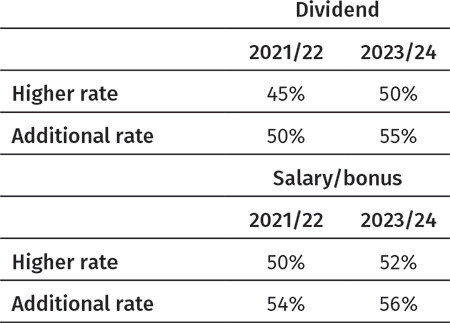

For both higher rate and additional rate taxpayers, taking dividends as opposed to a bonus will continue to be the best policy after April 2023, but it is very marginal. The wider point is that the tax rates are pretty high. The overall effective tax rates on profits being extracted from a company currently and after April 2023 (when the corporation tax rate goes up) are as follows:

These look pretty unattractive tax rates. Broadly the tax rates on profits taken by dividend goes up by 5% (which is mainly the corporation tax increase) and the tax rate on salary or bonuses increases, which is the NIC increase. You can’t just add the tax rate increases together, as the individual gets some tax relief on the corporation tax and employer’s NIC tax increases.

What it means is retaining money in a company is increasingly attractive, rather than withdrawing the profit. Also, if you want to take money out, then better to take a bigger dividend before 6 April 2022. After that, the additional dividend tax is £1,250 per £100,000 of dividend taken.

However you look at it, the increase in NIC is inflationary. Given the concerns over the outlook for inflation, this makes increasing NIC a very surprising approach to take.

The increase in employer’s NIC is certainly an employer cost. The question on the increase in employees’ NIC is whether, given the tightness of the labour market, it is passed onto the employer. It certainly seems very difficult to see how, at the moment, employers can pass their increase onto their employees. Therefore, if employers wish to protect their margins then they must pass the increase on to customers.

Consider a business where their wages to sales percentage is 50% (a typical service business metric). In that scenario, if the business is to maintain that percentage then sales will need to increase by 2.5%. If the business is selling to non-VAT registered customers (for example, hospitality), then sales prices need to increase by 3%.

The position will vary from business to business but given that there is already cost push inflation, then this NIC increase is only going to add to it.

The alternative is for businesses to try to reduce the size of their workforce to absorb the increase in wage costs. That suggests more automation, and this has already seemed the answer for many businesses given the loss of cheaper labour from Eastern Europe as a result of Brexit.

So, for many businesses the answer might be to try to increase prices in the short term and look to reduce labour input in the longer term. However, businesses that are labour intensive and do not have control of their pricing are in a difficult position. It seems ironic that the best example of a business in that position is a care home (their customers are typically local authorities who set the market price for fees).

A further point here is that there is considerable political pressure to increase low wages and promises to increase the minimum wage are likely to feature in the next election manifestos. Life does not look like it will get any easier for labour intensive businesses and it seems quite likely that the health and social care levy will increase further in future.

Whilst measuring the tax burden as a proportion of GDP is an imperfect measure, it does give a basis for comparison over time. The widely quoted figures are that the corporation tax rise announced in March amounted to taking us back to the position of the tax burden in 1969. The health and social care levy announcement takes us back another 19 years to 1950.

Given the hard graft my father’s generation had to put in to reduce that tax burden, it seems depressing how quickly both the tax burden and national debt have increased. In the end, the debt burden ends up on our productive capacity and the danger is that it is seen as too easy to keep increasing the tax burden on business.

The other part of this measure that is interesting from a tax policy perspective is that, rather than being announced as part of a Budget or a spending review, it was introduced as a standalone measure by the prime minister and the health secretary – more like a US tax measure, and perhaps marking the shape of things to come.

Inflationary pressures, increased tax rates on profit extraction and an overall tax burden taking us back to 1950.

As the dust settles on the government’s decision to increase NICs from April next year – and its conversion into the health and social care levy from 2023 – it is helpful to reflect on the wider implications for business and the tax system.

It is also important to consider the impact of this tax rise alongside the already announced increase in corporation tax to 25% from April 2023, the outlook for UK tax policy more generally and wider economic factors.

Specifically, the NIC increase has implications for:

Profit extraction from companies: Both the corporation tax increase announced in March, and higher NIC, up the overall tax rate on profits earned in a company and then extracted by the owner.

For both higher rate and additional rate taxpayers, taking dividends as opposed to a bonus will continue to be the best policy after April 2023, but it is very marginal. The wider point is that the tax rates are pretty high. The overall effective tax rates on profits being extracted from a company currently and after April 2023 (when the corporation tax rate goes up) are as follows:

These look pretty unattractive tax rates. Broadly the tax rates on profits taken by dividend goes up by 5% (which is mainly the corporation tax increase) and the tax rate on salary or bonuses increases, which is the NIC increase. You can’t just add the tax rate increases together, as the individual gets some tax relief on the corporation tax and employer’s NIC tax increases.

What it means is retaining money in a company is increasingly attractive, rather than withdrawing the profit. Also, if you want to take money out, then better to take a bigger dividend before 6 April 2022. After that, the additional dividend tax is £1,250 per £100,000 of dividend taken.

However you look at it, the increase in NIC is inflationary. Given the concerns over the outlook for inflation, this makes increasing NIC a very surprising approach to take.

The increase in employer’s NIC is certainly an employer cost. The question on the increase in employees’ NIC is whether, given the tightness of the labour market, it is passed onto the employer. It certainly seems very difficult to see how, at the moment, employers can pass their increase onto their employees. Therefore, if employers wish to protect their margins then they must pass the increase on to customers.

Consider a business where their wages to sales percentage is 50% (a typical service business metric). In that scenario, if the business is to maintain that percentage then sales will need to increase by 2.5%. If the business is selling to non-VAT registered customers (for example, hospitality), then sales prices need to increase by 3%.

The position will vary from business to business but given that there is already cost push inflation, then this NIC increase is only going to add to it.

The alternative is for businesses to try to reduce the size of their workforce to absorb the increase in wage costs. That suggests more automation, and this has already seemed the answer for many businesses given the loss of cheaper labour from Eastern Europe as a result of Brexit.

So, for many businesses the answer might be to try to increase prices in the short term and look to reduce labour input in the longer term. However, businesses that are labour intensive and do not have control of their pricing are in a difficult position. It seems ironic that the best example of a business in that position is a care home (their customers are typically local authorities who set the market price for fees).

A further point here is that there is considerable political pressure to increase low wages and promises to increase the minimum wage are likely to feature in the next election manifestos. Life does not look like it will get any easier for labour intensive businesses and it seems quite likely that the health and social care levy will increase further in future.

Whilst measuring the tax burden as a proportion of GDP is an imperfect measure, it does give a basis for comparison over time. The widely quoted figures are that the corporation tax rise announced in March amounted to taking us back to the position of the tax burden in 1969. The health and social care levy announcement takes us back another 19 years to 1950.

Given the hard graft my father’s generation had to put in to reduce that tax burden, it seems depressing how quickly both the tax burden and national debt have increased. In the end, the debt burden ends up on our productive capacity and the danger is that it is seen as too easy to keep increasing the tax burden on business.

The other part of this measure that is interesting from a tax policy perspective is that, rather than being announced as part of a Budget or a spending review, it was introduced as a standalone measure by the prime minister and the health secretary – more like a US tax measure, and perhaps marking the shape of things to come.