The Office of Tax Simplification has carried out the first wide-ranging simplification review of the UK’s VAT system. In its report, the OTS’s core recommendations include: that the government should examine the current approach to the level and design of the VAT registration threshold, with a view to setting out a future direction of travel for the threshold, including consideration of the potential benefits of a smoothing mechanism; that HMRC should maintain a programme for further improving the clarity of its guidance and its responsiveness to requests for rulings in areas of uncertainty; and that HM Treasury and HMRC should undertake a comprehensive review of the reduced rate, zero-rate and exemption schedules. The OTS’s recommendations are for improving the day to day administration of the tax, including a less uncertain penalty system. Areas of technical difficulty which the OTS considers include the partial exemption regime, the capital goods scheme, the option to tax and other special schemes.

The key findings and recommendations in the OTS report on the UK’s VAT system, together with the chancellor’s responses, by Nigel Mellor (The Office of Tax Simplification).

On 7 November 2017, the Office of Tax Simplification laid before Parliament its latest report entitled Value added tax: routes to simplification.

The OTS is a small team of independent, expert advisers who undertake detailed research into tax complexity issues typically on behalf of ministers but it can undertake reviews at its own instigation.

This is the first major review of the VAT system in over 40 years and it is the product of a 12-month review of the workings of the UK VAT system. The OTS held over 80 meetings with various stakeholders during the course of its research. These ranged from private individuals through to some of the largest corporations, professional bodies, trade associations as well as HM Treasury and HMRC.

The review was first announced in the chancellor’s Autumn Statement and the terms of reference were published on 8 December 2016. The OTS was asked to consider whether the VAT system is working appropriately in today’s economy and to identify simplification opportunities. In total, the report contains 23 recommendations, of which eight are described as core recommendations and 15 as additional recommendations.

In February 2017, an interim report was published together with a call for evidence. The interim report identified the VAT threshold, multiple rates, partial exemption, the option to tax and the capital goods scheme as areas commonly considered to be those creating the greatest complexity. In addition, apart from these technical issues, the interim report also said that the administration of the tax would be reviewed to identify what are frequently described as friction points in the administration of the tax. The report can be broken down into three main areas; namely,

The UK’s £85,000 VAT registration threshold is the highest threshold in both the EU, where the average is £20,000, and the OECD. The high threshold is often itself seen as a tax simplification measure, as many businesses can operate without needing to be registered for VAT; for example, many largely labour-based business owners told us that they are content to operate on the basis of a turnover below the threshold. However, as the report explains in detail, there is clear evidence, from academic analysis of HMRC data and from submissions to this review, that the high level of the threshold is having a distortionary impact on business growth and activity.

Bunching

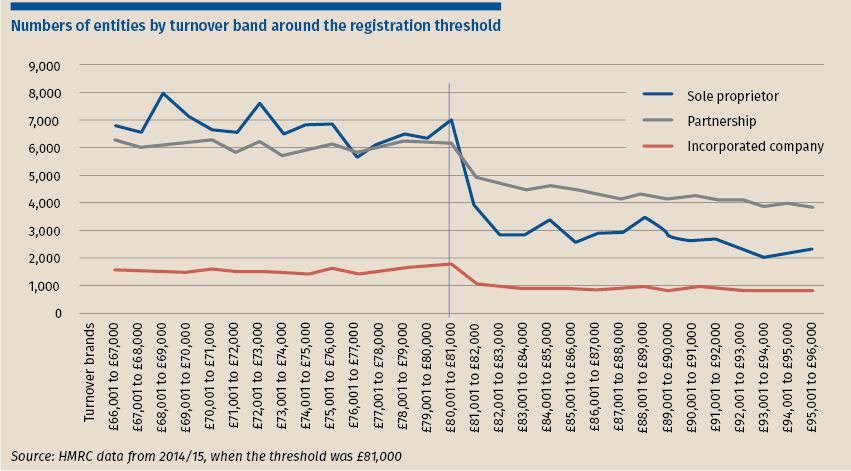

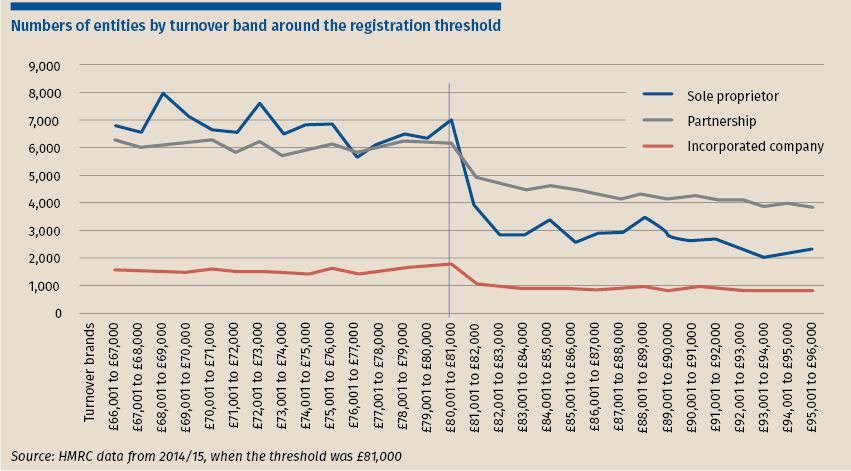

There is currently significant ‘bunching’ of businesses whose turnover is just below the threshold (see chart below), particularly businesses with lower levels of inputs relative to supplies to consumers – such as labour-intensive businesses, and businesses operated by sole proprietors – for whom this bunching effect has the appearance of a cliff edge.

The bunching in front of the threshold and the very significant fall-off in business numbers immediately after it, reflects the significance to a business of crossing the threshold, as when this happens all of a businesses’ supplies to customers potentially increase its sale price by up to 20%.

Evidently, many businesses will not be able to pass this increase on to customers, especially when competing with unregistered businesses. Meanwhile, others fear the administrative impact of VAT registration.

Bunching arises in two main ways. Firstly, some businesses limit expansion: for example, by not taking on an extra employee, or an extra contract, or closing their doors for a period, to keep their turnover below the threshold. Secondly, some businesses deliberately suppress their recorded takings and then report a turnover below the threshold.

More broadly, the fact that many taxpayers are spending time considering these issues and the impact on their business, and adapting their behaviour to avoid either the economic or administrative consequences of entering the VAT system, is itself an undesirable complexity in terms of the ‘user experience’ of VAT as well as being potentially economically distortive.

The OTS has considered the impact of either raising or lowering the threshold, both by small or larger amounts.

What would the impact be of making smaller changes to the threshold?

Freezing the threshold is one option (and is being adopted by the government, for the time being at least, while consulting in this area). If the government had maintained the existing threshold in 2017/18 (rather than increasing it in line with inflation as has become the norm), 4,000 extra businesses would potentially have been required to register in that year, with an increase in revenue to the public purse of approximately £10m and a consequent increase in the administrative costs of those businesses. (If the freeze were continued into future years, the numbers brought into VAT and the revenues involved would continue to grow.)

Reducing the threshold a little would mean that a few thousand additional businesses would be required to register, increasing their tax compliance costs.

Either freezing or slightly reducing the threshold would have limited impact on competitive distortions however, because only a small number of businesses would be affected relative to the overall UK business population, and the behavioural consequence might only be to shift the point at which bunching occurs.

Increasing the threshold by a small amount, say £2,000, would mean that approximately 12,000 to 15,000 fewer businesses would be required to register. This would produce some administrative savings for those businesses, but again have limited impact on competitive distortions. Tax revenue would be reduced by between £30m to £50m in the first year, increasing over time. As with small reductions, the behavioural consequence might only be to shift the point where bunching occurs.

However, the revenue and administrative impacts would, clearly, be greater if the threshold were raised or lowered by a more substantial amount.

What if significant changes were made to the threshold?

Raising the threshold significantly, for example to £500,000, would potentially impact around 800,000 businesses. Of those, between 400,000 and 600,000 businesses might choose to deregister, while 200,000–400,000 might choose to remain voluntarily registered. This would simplify the tax obligations for businesses that chose to deregister, reduce VAT-related competitive distortions between registered and unregistered small businesses, and reduce the administrative burden on those businesses.

However, raising the threshold to such a high level would cut the funds available for public services by between £3bn and £6bn a year. It would also have potential behavioural consequences. For example, the presence of many more unregistered businesses in the marketplace could well encourage some of them to operate in the hidden economy, reducing their compliance with, and payment of, other taxes. Competitive distortions would also be shifted upwards so medium-sized businesses would be in competition with many more unregistered businesses in total, some of which would be of substantial size.

Reducing the threshold from £85,000 to £43,000, for example, would impact between 400,000 and 600,000 businesses. This would reduce the unregistered business population and competitive distortions, and make it harder for businesses seeking to evade VAT to remain undiscovered. It would also raise between £1bn and £1.5bn a year.

However, it would increase compliance costs for a large number of businesses and involve additional costs for HMRC in managing this increased population of registered businesses.

It should be noted that significant changes to the VAT threshold would have implications going much wider than the simplification of VAT, including impacts on economic growth and productivity, on pricing, and the impact of VAT on those in different income brackets.

Potential smoothing mechanisms

Given that any threshold creates an incentive to operate below it, the OTS also considered ways in which the distortive effect of a threshold might be reduced by introducing some form of smoothing mechanism.

Options considered included:

Any such mechanism could be considered to increase the overall complexity of the system, but it could also offer businesses a way to pass more easily across the threshold and have a positive impact on economic growth and productivity.

Developing a workable mechanism that balances the risk of fraud, revenue loss and potential complexity against the benefits of smoothing entry to the VAT system and reducing business burdens is challenging, but the OTS considers there is merit in examining this for the future.

Core recommendation 1: The government should examine the current approach to the level and design of the VAT registration threshold, with a view to setting out a future direction of travel for the threshold, including consideration of the potential benefits of a smoothing mechanism.

The chancellor’s response: ‘I am grateful for the research and analysis conducted by the OTS on the issues and impacts around raising or lowering the VAT registration threshold, and note in particular the distortive impact that the current threshold appears to have on business behaviour. I agree with your recommendation to examine the VAT registration threshold but I am minded to keep it at its current level of £85,000 whilst we consider the issues raised.’

Practical administrative issues are often the most important to users of the tax system and many contributors identified areas where improvements could make life easier for businesses.

Guidance and rulings

Businesses benefit from certainty when making decisions about the VAT treatment of goods and services they supply, and/or when dealing with one-off events such as a complex restructuring. If they get the VAT treatment wrong, then they and their customers may be exposed to additional costs.

A range of concerns were raised with us about the comprehensiveness of parts of HMRC guidance and its response to requests for rulings. In particular, this included examples provided to us where HMRC has referred taxpayers back to the guidance that they have already found to be insufficient. The report also points out that a number of other common law countries have now started to publish suitably anonymised rulings. These rulings are generally binding on the revenue authority and feedback from many stakeholders was that publication of such generic rulings would be welcomed.

Core recommendation 2: HMRC should maintain a programme for further improving the clarity of its guidance and its responsiveness to requests for rulings in areas of uncertainty.

The chancellor’s response: ‘I appreciate that practical administrative issues are of importance to businesses working within the VAT system, and that those businesses benefit from clear guidance and rulings. The government is committed to simplifying the tax system and, where there is uncertainty, making relevant information readily accessible. I am keen to ensure that progress in this area continues.’

Voluntary disclosures and penalties

Clearly, errors can occur even in the best-managed businesses. HMRC recognises this and encourages businesses to voluntarily disclose errors found. The current voluntary disclosure procedures allow for small inaccuracies to be adjusted on a subsequent return by the business. However, although small inaccuracies can be adjusted in this way, businesses are still required to notify HMRC about the inaccuracy for penalty consideration purposes even though very few such voluntary disclosures lead to a penalty in practice. This was identified by many businesses as creating uncertainty.

Core recommendation 3: HMRC should consider ways of reducing the uncertainty and administrative costs for business relating to potential penalties when inaccuracies are voluntarily disclosed.

The chancellor’s response: ‘Your report highlights the administrative costs and uncertainty for business when voluntarily disclosing inaccuracies. I have therefore asked officials in HMRC to consider ways of addressing these issues in future.’

Appeals and ADR

As with penalties, disputes between businesses and HMRC are a significant friction point and the OTS considers that more can be done to alleviate this. Many respondents to our review regarded the statutory review process as being a rubber-stamping exercise, generally upholding the original decision. During the course of the review the OTS came to the conclusion that this is not a fair criticism of HMRC but nevertheless this perception exists and should not be ignored. Consequently, ways to address this issue were suggested in the report. In a similar vein, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is increasingly being used as a way of resolving tax disputes between businesses and HMRC. ADR was fairly widely praised as a useful way to resolve disputes but many respondents shared concerns about the cost of the process. Consequently, this issue is addressed in the report and ways of easing the friction are recommended.

Multiple rates

Goods or services are standard rated by default. The law then provides various exceptions under which goods and services may be subject to a reduced rate or zero-rated, or may be exempt from VAT. Certain sectors, for example charities, may also have non-business income which is outside the scope of the tax.

These VAT rates, their scope and any changes to them, are limited to an extent by the framework of EU law, at least for as long as the UK remains within the EU. Although the UK can replace reduced or zero-rates with the standard rate, it is not able to enlarge the scope of those lower rates outside of EU law, and if any supplies are removed from the scope of zero-rates this treatment could not then be reinstated.

The boundaries between these treatments are often a cause of complexity, and are administratively burdensome. The scale of this is now such that the OTS considers that it is time for a comprehensive review of these issues. This should be aimed at simplifying the rates structure, and considering ways to frame them so they can better adapt to changes in government objectives, the market and technology. Such work will also provide a useful basis for the consideration of potential approaches in this area post Brexit.

Core recommendation 4: HMT and HMRC should undertake a comprehensive review of the reduced rate, zero-rate and exemption schedules, working with the support of the OTS.

The chancellor’s response: ‘The government’s ability to amend the scope of the various rates and exemptions is limited to some extent by EU law at present. It is clear that the current rates, structure is the root cause of much of the complexity in the VAT system, imposing administrative burdens on businesses and often confusing customers. I agree that there is merit in a review of the current system of VAT rates and reliefs in the longer term, and HMRC and HM Treasury officials will continue to engage with the OTS on this subject.’

Partial exemption

The partial exemption regime has evolved over 40 years and is now capturing many businesses that would not originally have been affected by it. This is mainly because the de minimis limits, intended to ensure smaller businesses did not find themselves with small amounts of irrecoverable input tax, have not been increased for decades.

In addition, businesses that need HMRC approval for a method for calculating how much tax they can recover have expressed significant concerns about the time required – sometimes up to two years – to obtain approval of proposed methods.

Core recommendation 5: The government should consider increasing the partial exemption de minimis limits in line with inflation, and explore alternative ways of removing the need for businesses incurring insignificant amounts of input tax to carry out partial exemption calculations.

Core recommendation 6: HMRC should consider further ways to simplify partial exemption calculations and to improve the process of making and agreeing special method applications.

Capital goods scheme

Input tax recovery is generally determined by the use to which the expenditure is to be put at the time it is incurred. The capital goods scheme (CGS) aims to ensure that input tax recovery on major items of expenditure reflects the use of an asset for taxable or exempt purposes over time, by calculating a recovery percentage once a year.

The assets that fall within the CGS are:

Each year after the purchase or first use of the asset, the business must consider whether the proportions of its taxable and exempt use have changed.

Take, for example, a business that purchases a building and intends to use it for the purposes of its fully taxable activities. On this basis, the business is entitled to fully recover the input tax that it has incurred. After a few years, the business changes and it decides to lease part of the building to another business. In the absence of an option to tax, the leasing activity would give rise to an exempt supply. At this point, the business has potentially over-claimed the input tax that it has incurred.

The CGS acts as a means of remedying this. It operates over a period of five years (for computers, boats and aircraft) or ten years (for land and property).

However, there are several issues with the scheme. The first is that the threshold for land and buildings has not been raised since the introduction of the CGS in 1990, with the result that many more transactions are now in the scheme than was originally anticipated. In addition, the scheme also includes extensions and refurbishment of existing buildings, so some taxpayers have multiple CGS calculations running for varying amounts of time. The time and administration required for relatively small adjustments is significant for business.

Another issue is that the threshold for computers was introduced at a time when single items of computer equipment were of high value. Changes in technology and the value of computer systems means that it is now rare for a single piece of equipment to breach the threshold.

Core recommendation 7: The government should consider whether capital goods scheme categories other than for land and property are needed, and review the land and property threshold.

The chancellor’s response in relation to recommendations 5, 6 and 7: ‘Your report raises concerns about the existing partial exemption regime and capital goods scheme. I would encourage the OTS to continue to engage with HMRC and HM Treasury officials in these areas.’

Option to tax

Supplies of commercial land and buildings (other than of those less than three years old) are by default exempt from VAT. The option to tax provides businesses with the ability to change what would otherwise be an exempt supply of commercial land or buildings to a taxable supply, thus enabling input tax recovery on costs associated with that supply.

Opting to tax is a relatively simple process, but it can take some time for HMRC to acknowledge receipt of the option. Businesses sometimes believe an option is automatically in place if the owner or previous owner has opted, not realising that each person has to make their own decision to opt their interest in the land or buildings. As there is no universal record of who has opted in relation to what property interests, uncertainty about whether a piece of land or a building has been opted can cause difficulties when the land or building is being sold.

Core recommendation 8: HMRC should review the current requirements for record keeping and the audit trail for options to tax, and the extent to which this might be handled online.

Brexit

The terms of reference for this review stated that it would not ‘focus on issues likely to be significant in the context of the government’s consideration of Brexit, such as the treatment of financial services, statistical reporting and EU cross-border VAT rules. However, it will actively bear the Brexit context in mind in looking at opportunities to simplify VAT for the future’.

It is too early at this stage of the Brexit process to gauge the extent or timing of its impact on VAT. However, in the longer term, Brexit may offer opportunities to consider areas that might otherwise have been difficult to simplify.

Some respondents made the case for including VAT on financial services within the scope of this report. However, the OTS considers the simplification of this important part of the VAT system would be better dealt with once the shape of Brexit negotiations and the legislative implications of Brexit become clearer, and the resulting pressure on parliamentary time eases.

In addition to the core recommendations, the OTS has made 15 additional recommendations which are set out below together with an indication as to whether they are short term or longer term objectives (see table below).

The Office of Tax Simplification has carried out the first wide-ranging simplification review of the UK’s VAT system. In its report, the OTS’s core recommendations include: that the government should examine the current approach to the level and design of the VAT registration threshold, with a view to setting out a future direction of travel for the threshold, including consideration of the potential benefits of a smoothing mechanism; that HMRC should maintain a programme for further improving the clarity of its guidance and its responsiveness to requests for rulings in areas of uncertainty; and that HM Treasury and HMRC should undertake a comprehensive review of the reduced rate, zero-rate and exemption schedules. The OTS’s recommendations are for improving the day to day administration of the tax, including a less uncertain penalty system. Areas of technical difficulty which the OTS considers include the partial exemption regime, the capital goods scheme, the option to tax and other special schemes.

The key findings and recommendations in the OTS report on the UK’s VAT system, together with the chancellor’s responses, by Nigel Mellor (The Office of Tax Simplification).

On 7 November 2017, the Office of Tax Simplification laid before Parliament its latest report entitled Value added tax: routes to simplification.

The OTS is a small team of independent, expert advisers who undertake detailed research into tax complexity issues typically on behalf of ministers but it can undertake reviews at its own instigation.

This is the first major review of the VAT system in over 40 years and it is the product of a 12-month review of the workings of the UK VAT system. The OTS held over 80 meetings with various stakeholders during the course of its research. These ranged from private individuals through to some of the largest corporations, professional bodies, trade associations as well as HM Treasury and HMRC.

The review was first announced in the chancellor’s Autumn Statement and the terms of reference were published on 8 December 2016. The OTS was asked to consider whether the VAT system is working appropriately in today’s economy and to identify simplification opportunities. In total, the report contains 23 recommendations, of which eight are described as core recommendations and 15 as additional recommendations.

In February 2017, an interim report was published together with a call for evidence. The interim report identified the VAT threshold, multiple rates, partial exemption, the option to tax and the capital goods scheme as areas commonly considered to be those creating the greatest complexity. In addition, apart from these technical issues, the interim report also said that the administration of the tax would be reviewed to identify what are frequently described as friction points in the administration of the tax. The report can be broken down into three main areas; namely,

The UK’s £85,000 VAT registration threshold is the highest threshold in both the EU, where the average is £20,000, and the OECD. The high threshold is often itself seen as a tax simplification measure, as many businesses can operate without needing to be registered for VAT; for example, many largely labour-based business owners told us that they are content to operate on the basis of a turnover below the threshold. However, as the report explains in detail, there is clear evidence, from academic analysis of HMRC data and from submissions to this review, that the high level of the threshold is having a distortionary impact on business growth and activity.

Bunching

There is currently significant ‘bunching’ of businesses whose turnover is just below the threshold (see chart below), particularly businesses with lower levels of inputs relative to supplies to consumers – such as labour-intensive businesses, and businesses operated by sole proprietors – for whom this bunching effect has the appearance of a cliff edge.

The bunching in front of the threshold and the very significant fall-off in business numbers immediately after it, reflects the significance to a business of crossing the threshold, as when this happens all of a businesses’ supplies to customers potentially increase its sale price by up to 20%.

Evidently, many businesses will not be able to pass this increase on to customers, especially when competing with unregistered businesses. Meanwhile, others fear the administrative impact of VAT registration.

Bunching arises in two main ways. Firstly, some businesses limit expansion: for example, by not taking on an extra employee, or an extra contract, or closing their doors for a period, to keep their turnover below the threshold. Secondly, some businesses deliberately suppress their recorded takings and then report a turnover below the threshold.

More broadly, the fact that many taxpayers are spending time considering these issues and the impact on their business, and adapting their behaviour to avoid either the economic or administrative consequences of entering the VAT system, is itself an undesirable complexity in terms of the ‘user experience’ of VAT as well as being potentially economically distortive.

The OTS has considered the impact of either raising or lowering the threshold, both by small or larger amounts.

What would the impact be of making smaller changes to the threshold?

Freezing the threshold is one option (and is being adopted by the government, for the time being at least, while consulting in this area). If the government had maintained the existing threshold in 2017/18 (rather than increasing it in line with inflation as has become the norm), 4,000 extra businesses would potentially have been required to register in that year, with an increase in revenue to the public purse of approximately £10m and a consequent increase in the administrative costs of those businesses. (If the freeze were continued into future years, the numbers brought into VAT and the revenues involved would continue to grow.)

Reducing the threshold a little would mean that a few thousand additional businesses would be required to register, increasing their tax compliance costs.

Either freezing or slightly reducing the threshold would have limited impact on competitive distortions however, because only a small number of businesses would be affected relative to the overall UK business population, and the behavioural consequence might only be to shift the point at which bunching occurs.

Increasing the threshold by a small amount, say £2,000, would mean that approximately 12,000 to 15,000 fewer businesses would be required to register. This would produce some administrative savings for those businesses, but again have limited impact on competitive distortions. Tax revenue would be reduced by between £30m to £50m in the first year, increasing over time. As with small reductions, the behavioural consequence might only be to shift the point where bunching occurs.

However, the revenue and administrative impacts would, clearly, be greater if the threshold were raised or lowered by a more substantial amount.

What if significant changes were made to the threshold?

Raising the threshold significantly, for example to £500,000, would potentially impact around 800,000 businesses. Of those, between 400,000 and 600,000 businesses might choose to deregister, while 200,000–400,000 might choose to remain voluntarily registered. This would simplify the tax obligations for businesses that chose to deregister, reduce VAT-related competitive distortions between registered and unregistered small businesses, and reduce the administrative burden on those businesses.

However, raising the threshold to such a high level would cut the funds available for public services by between £3bn and £6bn a year. It would also have potential behavioural consequences. For example, the presence of many more unregistered businesses in the marketplace could well encourage some of them to operate in the hidden economy, reducing their compliance with, and payment of, other taxes. Competitive distortions would also be shifted upwards so medium-sized businesses would be in competition with many more unregistered businesses in total, some of which would be of substantial size.

Reducing the threshold from £85,000 to £43,000, for example, would impact between 400,000 and 600,000 businesses. This would reduce the unregistered business population and competitive distortions, and make it harder for businesses seeking to evade VAT to remain undiscovered. It would also raise between £1bn and £1.5bn a year.

However, it would increase compliance costs for a large number of businesses and involve additional costs for HMRC in managing this increased population of registered businesses.

It should be noted that significant changes to the VAT threshold would have implications going much wider than the simplification of VAT, including impacts on economic growth and productivity, on pricing, and the impact of VAT on those in different income brackets.

Potential smoothing mechanisms

Given that any threshold creates an incentive to operate below it, the OTS also considered ways in which the distortive effect of a threshold might be reduced by introducing some form of smoothing mechanism.

Options considered included:

Any such mechanism could be considered to increase the overall complexity of the system, but it could also offer businesses a way to pass more easily across the threshold and have a positive impact on economic growth and productivity.

Developing a workable mechanism that balances the risk of fraud, revenue loss and potential complexity against the benefits of smoothing entry to the VAT system and reducing business burdens is challenging, but the OTS considers there is merit in examining this for the future.

Core recommendation 1: The government should examine the current approach to the level and design of the VAT registration threshold, with a view to setting out a future direction of travel for the threshold, including consideration of the potential benefits of a smoothing mechanism.

The chancellor’s response: ‘I am grateful for the research and analysis conducted by the OTS on the issues and impacts around raising or lowering the VAT registration threshold, and note in particular the distortive impact that the current threshold appears to have on business behaviour. I agree with your recommendation to examine the VAT registration threshold but I am minded to keep it at its current level of £85,000 whilst we consider the issues raised.’

Practical administrative issues are often the most important to users of the tax system and many contributors identified areas where improvements could make life easier for businesses.

Guidance and rulings

Businesses benefit from certainty when making decisions about the VAT treatment of goods and services they supply, and/or when dealing with one-off events such as a complex restructuring. If they get the VAT treatment wrong, then they and their customers may be exposed to additional costs.

A range of concerns were raised with us about the comprehensiveness of parts of HMRC guidance and its response to requests for rulings. In particular, this included examples provided to us where HMRC has referred taxpayers back to the guidance that they have already found to be insufficient. The report also points out that a number of other common law countries have now started to publish suitably anonymised rulings. These rulings are generally binding on the revenue authority and feedback from many stakeholders was that publication of such generic rulings would be welcomed.

Core recommendation 2: HMRC should maintain a programme for further improving the clarity of its guidance and its responsiveness to requests for rulings in areas of uncertainty.

The chancellor’s response: ‘I appreciate that practical administrative issues are of importance to businesses working within the VAT system, and that those businesses benefit from clear guidance and rulings. The government is committed to simplifying the tax system and, where there is uncertainty, making relevant information readily accessible. I am keen to ensure that progress in this area continues.’

Voluntary disclosures and penalties

Clearly, errors can occur even in the best-managed businesses. HMRC recognises this and encourages businesses to voluntarily disclose errors found. The current voluntary disclosure procedures allow for small inaccuracies to be adjusted on a subsequent return by the business. However, although small inaccuracies can be adjusted in this way, businesses are still required to notify HMRC about the inaccuracy for penalty consideration purposes even though very few such voluntary disclosures lead to a penalty in practice. This was identified by many businesses as creating uncertainty.

Core recommendation 3: HMRC should consider ways of reducing the uncertainty and administrative costs for business relating to potential penalties when inaccuracies are voluntarily disclosed.

The chancellor’s response: ‘Your report highlights the administrative costs and uncertainty for business when voluntarily disclosing inaccuracies. I have therefore asked officials in HMRC to consider ways of addressing these issues in future.’

Appeals and ADR

As with penalties, disputes between businesses and HMRC are a significant friction point and the OTS considers that more can be done to alleviate this. Many respondents to our review regarded the statutory review process as being a rubber-stamping exercise, generally upholding the original decision. During the course of the review the OTS came to the conclusion that this is not a fair criticism of HMRC but nevertheless this perception exists and should not be ignored. Consequently, ways to address this issue were suggested in the report. In a similar vein, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is increasingly being used as a way of resolving tax disputes between businesses and HMRC. ADR was fairly widely praised as a useful way to resolve disputes but many respondents shared concerns about the cost of the process. Consequently, this issue is addressed in the report and ways of easing the friction are recommended.

Multiple rates

Goods or services are standard rated by default. The law then provides various exceptions under which goods and services may be subject to a reduced rate or zero-rated, or may be exempt from VAT. Certain sectors, for example charities, may also have non-business income which is outside the scope of the tax.

These VAT rates, their scope and any changes to them, are limited to an extent by the framework of EU law, at least for as long as the UK remains within the EU. Although the UK can replace reduced or zero-rates with the standard rate, it is not able to enlarge the scope of those lower rates outside of EU law, and if any supplies are removed from the scope of zero-rates this treatment could not then be reinstated.

The boundaries between these treatments are often a cause of complexity, and are administratively burdensome. The scale of this is now such that the OTS considers that it is time for a comprehensive review of these issues. This should be aimed at simplifying the rates structure, and considering ways to frame them so they can better adapt to changes in government objectives, the market and technology. Such work will also provide a useful basis for the consideration of potential approaches in this area post Brexit.

Core recommendation 4: HMT and HMRC should undertake a comprehensive review of the reduced rate, zero-rate and exemption schedules, working with the support of the OTS.

The chancellor’s response: ‘The government’s ability to amend the scope of the various rates and exemptions is limited to some extent by EU law at present. It is clear that the current rates, structure is the root cause of much of the complexity in the VAT system, imposing administrative burdens on businesses and often confusing customers. I agree that there is merit in a review of the current system of VAT rates and reliefs in the longer term, and HMRC and HM Treasury officials will continue to engage with the OTS on this subject.’

Partial exemption

The partial exemption regime has evolved over 40 years and is now capturing many businesses that would not originally have been affected by it. This is mainly because the de minimis limits, intended to ensure smaller businesses did not find themselves with small amounts of irrecoverable input tax, have not been increased for decades.

In addition, businesses that need HMRC approval for a method for calculating how much tax they can recover have expressed significant concerns about the time required – sometimes up to two years – to obtain approval of proposed methods.

Core recommendation 5: The government should consider increasing the partial exemption de minimis limits in line with inflation, and explore alternative ways of removing the need for businesses incurring insignificant amounts of input tax to carry out partial exemption calculations.

Core recommendation 6: HMRC should consider further ways to simplify partial exemption calculations and to improve the process of making and agreeing special method applications.

Capital goods scheme

Input tax recovery is generally determined by the use to which the expenditure is to be put at the time it is incurred. The capital goods scheme (CGS) aims to ensure that input tax recovery on major items of expenditure reflects the use of an asset for taxable or exempt purposes over time, by calculating a recovery percentage once a year.

The assets that fall within the CGS are:

Each year after the purchase or first use of the asset, the business must consider whether the proportions of its taxable and exempt use have changed.

Take, for example, a business that purchases a building and intends to use it for the purposes of its fully taxable activities. On this basis, the business is entitled to fully recover the input tax that it has incurred. After a few years, the business changes and it decides to lease part of the building to another business. In the absence of an option to tax, the leasing activity would give rise to an exempt supply. At this point, the business has potentially over-claimed the input tax that it has incurred.

The CGS acts as a means of remedying this. It operates over a period of five years (for computers, boats and aircraft) or ten years (for land and property).

However, there are several issues with the scheme. The first is that the threshold for land and buildings has not been raised since the introduction of the CGS in 1990, with the result that many more transactions are now in the scheme than was originally anticipated. In addition, the scheme also includes extensions and refurbishment of existing buildings, so some taxpayers have multiple CGS calculations running for varying amounts of time. The time and administration required for relatively small adjustments is significant for business.

Another issue is that the threshold for computers was introduced at a time when single items of computer equipment were of high value. Changes in technology and the value of computer systems means that it is now rare for a single piece of equipment to breach the threshold.

Core recommendation 7: The government should consider whether capital goods scheme categories other than for land and property are needed, and review the land and property threshold.

The chancellor’s response in relation to recommendations 5, 6 and 7: ‘Your report raises concerns about the existing partial exemption regime and capital goods scheme. I would encourage the OTS to continue to engage with HMRC and HM Treasury officials in these areas.’

Option to tax

Supplies of commercial land and buildings (other than of those less than three years old) are by default exempt from VAT. The option to tax provides businesses with the ability to change what would otherwise be an exempt supply of commercial land or buildings to a taxable supply, thus enabling input tax recovery on costs associated with that supply.

Opting to tax is a relatively simple process, but it can take some time for HMRC to acknowledge receipt of the option. Businesses sometimes believe an option is automatically in place if the owner or previous owner has opted, not realising that each person has to make their own decision to opt their interest in the land or buildings. As there is no universal record of who has opted in relation to what property interests, uncertainty about whether a piece of land or a building has been opted can cause difficulties when the land or building is being sold.

Core recommendation 8: HMRC should review the current requirements for record keeping and the audit trail for options to tax, and the extent to which this might be handled online.

Brexit

The terms of reference for this review stated that it would not ‘focus on issues likely to be significant in the context of the government’s consideration of Brexit, such as the treatment of financial services, statistical reporting and EU cross-border VAT rules. However, it will actively bear the Brexit context in mind in looking at opportunities to simplify VAT for the future’.

It is too early at this stage of the Brexit process to gauge the extent or timing of its impact on VAT. However, in the longer term, Brexit may offer opportunities to consider areas that might otherwise have been difficult to simplify.

Some respondents made the case for including VAT on financial services within the scope of this report. However, the OTS considers the simplification of this important part of the VAT system would be better dealt with once the shape of Brexit negotiations and the legislative implications of Brexit become clearer, and the resulting pressure on parliamentary time eases.

In addition to the core recommendations, the OTS has made 15 additional recommendations which are set out below together with an indication as to whether they are short term or longer term objectives (see table below).