The two pillars

On 9 October, the OECD secretary general published his report to the G20 finance ministers (see bit.ly/33n6sGw) in advance of their meeting on 17 October. The report included an update on progress on the Programme of Work adopted by the Inclusive Framework in May 2019 to address tax challenges arising from the increasing digitalisation of the economy (‘BEPS 2.0’, as to which see our article ‘BEPS 2.0: reshaping the architecture of international tax’, Tax Journal, 7 June 2019). This programme of work built on a policy note issued in January 2019 which provided for two ‘pillars’ to be developed with a view to reaching a global consensus-based solution by the end of 2020. Pillar one provided for a new allocation of taxing rights through new nexus and profit allocation rules and pillar two, the ‘GloBE’ proposal, sought to introduce measures to ensure a minimum level of tax. In an attempt to reconcile differences of opinion, alongside the report to the G20 finance ministers, the OECD Secretariat has published a proposal for a ‘unified approach’ under pillar one (‘the proposal’, see bit.ly/2IBrnxH).

The proposal, out for consultation until 12 November, does not yet represent consensus among the 134 Inclusive Framework members. However, it is hoped that this will break the deadlock between the three competing pillar one approaches outlined in the January 2019 policy note and help move the negotiations forward. Pillar two has not been forgotten: a consultation will be published on this in November, and work continues in the background but, for now, the spotlight is on pillar one.

The proposal highlights the commonalities between the three proposals (which, you may recall, were focused around user participation, marketing intangibles and significant economic presence). More importantly, it seeks to bridge the gaps between them, acknowledging that without doing so it will not be possible to deliver a consensus solution within the specified timeframe. The theme of the entire paper is trying to find a solution that countries can agree on. This is a colossal undertaking, but the OECD is well-equipped for the task and intent on forging a way forward. The proposal emphasises that ‘the future of multilateral tax cooperation’, ‘the intense political pressure to tax highly digitalised MNEs’ and ‘fundamental features of the international tax system’ all hang in the balance. The proposal cautions that ‘the stakes are very high’.

Who is affected?

The focus of the proposal is on large consumer-facing businesses. One possibility for defining ‘large’ might be by reference to revenue thresholds, with the €750m country by country reporting global threshold cited as an option. The BEPS Action 13 report indicated that such a threshold would exclude approximately 85 to 90% of MNE groups (see bit.ly/1Iij6tW).

The concept of ‘consumer-facing’ businesses intentionally extends beyond big tech companies but rather looks more generally towards those enterprises likely to derive meaningful value from interaction with consumers in market jurisdictions. This does not mean that B2B businesses are out. Although the focus will certainly be on B2C businesses, where a B2B business involves sales of consumer products through intermediaries, this is likely to be brought into scope. However, the focus on consumers does mean that there will be certain sectors with less engagement with the market where this rationale does not apply. The proposal indicates that extractive industries and commodities businesses are likely to be carved out on this basis. Financial services may follow suit, but discussions on this continue.

A new nexus rule

One of the commonalities between the three original proposals was the need to move beyond nexus based on physical presence. A test proposed in the Programme of Work was whether a multinational has a ‘sustained and significant involvement in the economy of a market jurisdiction’. The proposal suggests that this would be largely based on sales, noting that the simplest way to operate such a nexus rule would be to define a revenue threshold (which could be adapted to the size of the market to ensure smaller economies can benefit) as the primary indicator of sustained and significant involvement in the market. Another possibility, floated in the OECD webcast held on 9 October, would be to look at a time threshold; for example, whether the business had more than one year of activity in the market (presumably a nod to the ‘sustained’ aspect of the new nexus rule).

The proposal makes a point of highlighting that the new nexus rule will be a standalone concept, separate from permanent establishment (PE) concepts, on the basis that there is no desire to disturb existing bilateral treaty provisions and in an attempt to limit any unintended spillover effects. However, regardless of whether drafted as a self-standing treaty provision or as an amendment to the PE concept, the interaction between the two rules will have to be carefully crafted to prevent entities being subject to double taxation. The OECD is alive to this: one of the ‘pending key questions’ still to be explored is how the existing mechanisms for eliminating double taxation under both domestic law and treaties could operate under the unified approach.

New profit allocation rules

Having determined there is a new taxing right that can apply to non-residents with no physical presence in a jurisdiction, a new rule must also be created to allocate profit to this new nexus concept, as traditional income allocation rules would allocate no profit to it, rendering it redundant! The proposal therefore seeks to create a new profit allocation rule and the OECD is clearly taking a pragmatic approach to this. This does not necessarily involve finding the fairest solution, or even the best or most logically pure, but the key is to find a solution that all jurisdictions will get behind.

To do this, the OECD has proposed an ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ approach. Richard Collier of the OECD has emphasised that there is no appetite to sweep away the arm’s length principle (the ALP), and the proposal advocates keeping the ALP where it works well, but then supplementing it with a formulaic approach around the pressure points where disputes are prone to arise. This recognises the level of dissatisfaction, especially amongst developing countries, around the current complexity of the ALP as a tool for determining residual profits and the need for a simpler, ‘administrable’ solution in order to reduce disputes and minimise compliance costs.

A three-tier approach

So, how would this work? The proposal involves a three-tier profit allocation mechanism consisting of:

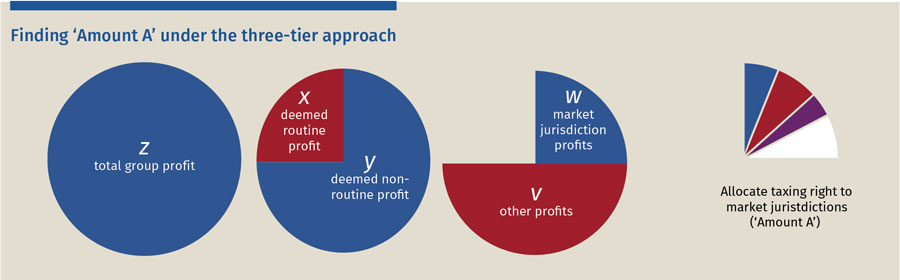

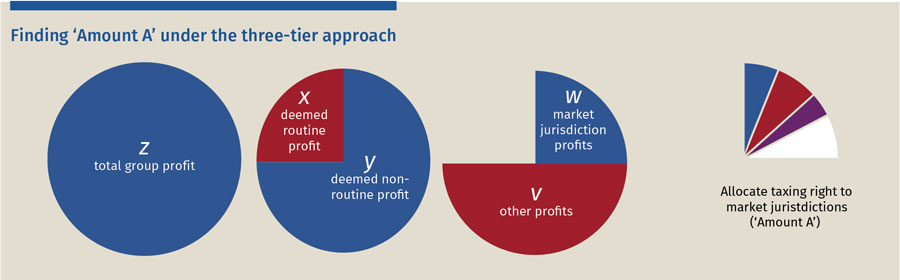

Amount A represents the ‘new taxing right’. You start by identifying the total group profit (‘z’ in the diagram below). This is likely to be based on consolidated financial statements under GAAP or IFRS, although there are still questions around whether this should be separated by business line or region.

The next step is calculating the routine profit where activities are performed (‘x’). This could be determined in a number of ways. To the extent that there is a desire to preserve the ALP where it works well, arguably there is a role for this here, but a simplified approach would be to agree a fixed percentage to be deducted. A slightly more nuanced version would use different percentages for different industries. The use of proxies is intended to simplify the calculation of amount A; the proposal insists that this is not intended to alter the remuneration for routine activities as calculated under the existing transfer pricing framework. It does, however, indicate a move away from the ‘significant economic presence’ option, in that the unified approach only seeks to re-allocate non-routine profits, whereas the significant economic presence proposal looked at re-allocating both routine and non-routine profits.

The amount that is left after deducting the routine profit (‘y’, being z-x) would then be split between the portion that is attributable to market jurisdictions (‘w’) and the portion that is attributable to other factors, such as trade intangibles (‘v’). The former amount (‘w’) would then be allocated between the markets that meet the new nexus rules through a formula based on sales. This is effectively amount A, i.e. the deemed residual profit that is subject to the new taxing right (see diagram above).

Amounts B and C are not about the new taxing right. Rather, these refer back to a traditional nexus with the market jurisdiction. The idea is that activities in the market jurisdiction would still be taxable under existing rules, including the ALP and looking at the activities of any PE in the market jurisdiction. However, it is hoped that having a fixed return reflecting an assumed baseline activity, amount B, could reduce the number of disputes relating to distribution functions.

Amount C is said to be designed to provide a mechanism to ease disputes. It is intended to allow additional profit in excess of amount B where there are more functions in the market jurisdiction than is assumed in the baseline. Any such amount must be supported by the application of the ALP. Although the OECD claims this is there to address the certainty agenda, in some ways it detracts from the formulaic certainty provided by amount B by re-opening the door to the uncertainties in the ALP. Perhaps we should also be wary of amount C’s application of the ALP leading to the use of a ‘bright line’ test resonating with the US case of DHL Inc and Subsidiaries v Commissioner (TCM 1998/461) which sought to determine whether local advertising/marketing/promotion (AMP) expenditure exceeded some measure of normality, which has led to significant litigation, for example in India. Again, the OECD is braced for this kind of issue, indicating that ‘robust measures’ to resolve disputes and prevent double taxation form an important part of this proposal. The consultation document invites respondents to share their experiences of unilateral and multilateral APAs, ICAP as well as mandatory binding MAP arbitration. Effective dispute resolution (and prevention) mechanisms will be fundamental to the success of the proposal, not only in preventing double taxation as between amounts A, B and C, but also between the new taxing right and existing rules.

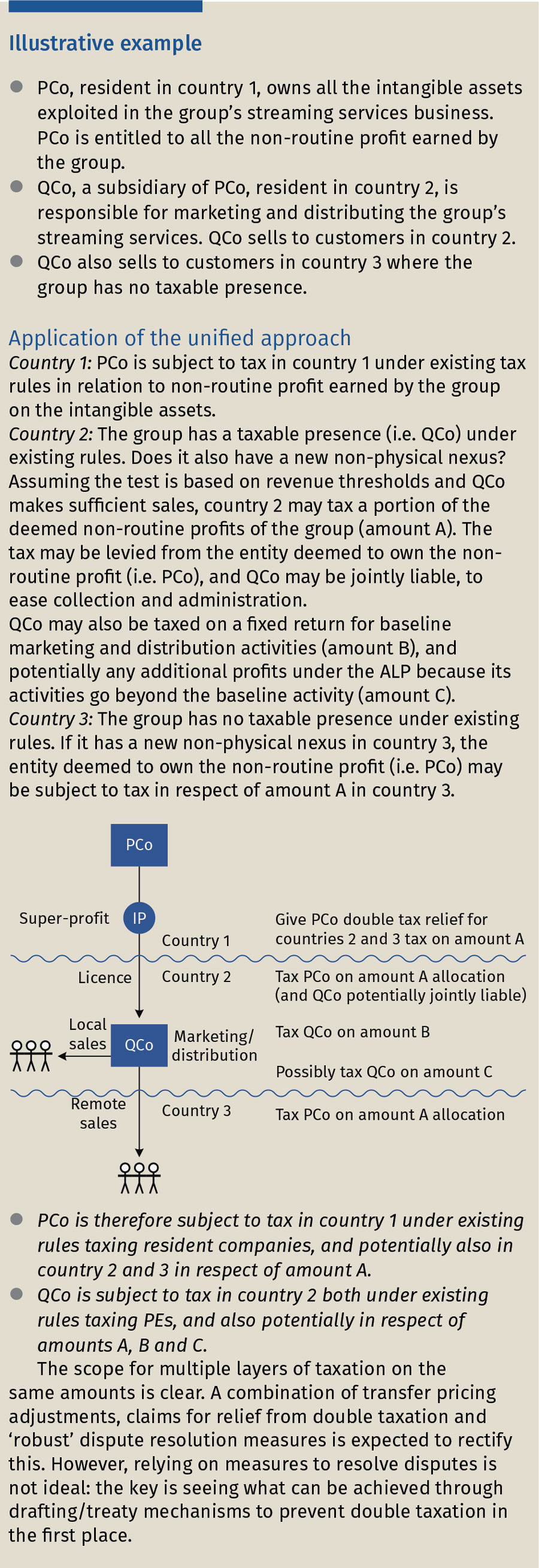

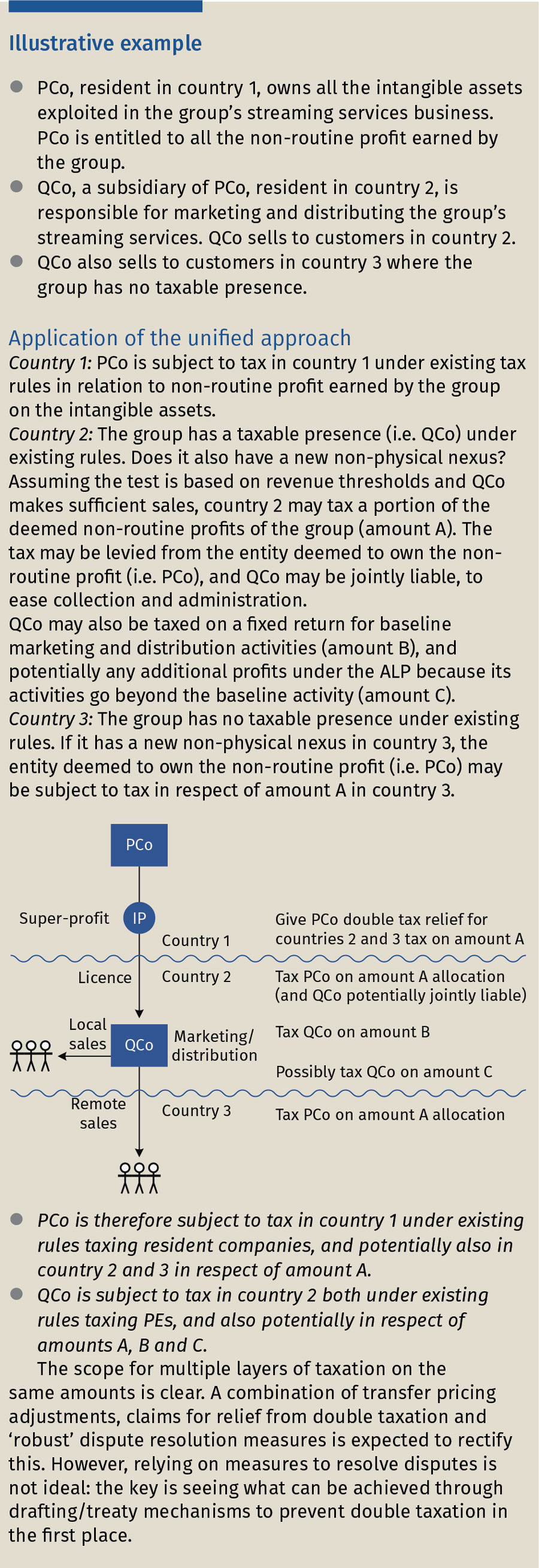

The proposal includes an example, illustrated in the box (below), which demonstrates that (i) each of amounts A, B and C, can arise in the jurisdiction where a group does have a taxable presence in the market jurisdiction and (ii) double taxation may arise as between the traditional taxing jurisdictions and the market jurisdictions in respect of amount A.

Implementation

Assuming the 134 members of the Inclusive Framework agree to this outline of the architecture for a unified approach to pillar one, how can it be achieved? Even though the new taxing right will be separate from the PE concept and so may not require changes to article 5 (permanent establishments) of the OECD Model Tax Convention, other changes to treaties, e.g. article 7 (business profits), will undoubtedly be required to allocate taxing rights over a non-resident’s business profits where there is no physical presence in the relevant jurisdiction. With the OECD of the view that changes to treaties would need to be ‘implemented simultaneously by all jurisdictions, to ensure a level playing field’, a second multilateral instrument (MLI 2.0?) seems inevitable.

Other thorny issues arise around enforcement and collection where amount A is assigned to an entity with no physical presence in a jurisdiction. Withholding tax is suggested as an option here. Another practical issue will be identifying which entity within the MNE group is treated as ‘owning’ the taxable profits in market jurisdictions under amount A and how would this interact with existing domestic and treaty relieving provisions.

Conclusion

There will be winners and losers under these proposals. The OECD report to finance ministers notes that pillar two would yield a ‘significant increase of corporate income tax revenue globally’ indicating that there will be a shift from income not being taxed to being taxed. This implies that there is still (despite the multitude of measures already introduced under BEPS) an issue with stateless income or with intangibles being held in tax havens. However, only a ‘modest’ increase in tax revenue is expected under pillar one. The shift here being from investment hubs (where analysis indicates there are high levels of residual profit) to market jurisdictions, particularly low and middle-income economies. However, the expectation is that larger market jurisdictions will benefit more in absolute terms. And this is crucial. There is an acknowledgement that there is no point pressing on with these proposals if the major players, such as the US and the EU will not agree. Pascal Saint-Amans, director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration has said that the US is on board and ‘that is the game-changer’.

Equally, with emerging economies and developing countries making up a large, and vocal, proportion of the Inclusive Framework, their interests cannot be ignored. This is why the proposal favours simplicity over fairness. The aim is to make the system simple to administer and the OECD’s pragmatic approach seems to be working. With the number of countries in the Inclusive Framework gradually rising, more and more countries are joining this attempt to reach global consensus.

There are, of course, a number of essential points that still need to be agreed, in terms of rates and thresholds and definitions. The Inclusive Framework members will be watching the impact assessments with a keen eye when it comes to fleshing out these points, particularly when it comes to setting rates, as these will be the crunch points that will make or break the proposals.

It has been suggested that the OECD proposals do not go far enough and that the OECD is ‘canonising gradualism’. Saint-Amans addressed these comments directly, indicating that this may indeed be what the OECD is doing given ‘we are not writing books for the shelves’. This is not an academic exercise looking at what the OECD thinks the world should do ‘in ideal circumstances’. Rather, his aim is to see how the rules can be changed so that ‘we have a better system, which is agreed by everybody and which changes things in practice’. As the saying goes, you can’t turn a tanker with a speedboat turn. And this is indeed a gargantuan tanker to turn. For some, it seems progress is not being made fast enough: the day after the OECD Secretariat’s proposal was published, Austria passed its unilateral digital advertising tax. It is measures like this that the OECD is striving to avoid. Asa Johansson, head of the OECD’s structural policies surveillance division, economics department, flagged that inaction by the OECD could lead to a further increase in tax uncertainty and a deterioration in the business and investment environment. Stabilising the system and improving certainty are the guiding principles behind the proposal.

And, whatever the critics may say, progress is being made on a grand scale. Huge shifts in thinking have already taken place. Formulary apportionment, previously rejected when floated in relation to the original BEPS project, is now front and centre of the proposals. The acceptance of nexus without physical presence marks a move towards destination-based tax, something discussed by economists in the 1990s but without ever gaining traction. And yet here we are. The tanker is turning.

The two pillars

On 9 October, the OECD secretary general published his report to the G20 finance ministers (see bit.ly/33n6sGw) in advance of their meeting on 17 October. The report included an update on progress on the Programme of Work adopted by the Inclusive Framework in May 2019 to address tax challenges arising from the increasing digitalisation of the economy (‘BEPS 2.0’, as to which see our article ‘BEPS 2.0: reshaping the architecture of international tax’, Tax Journal, 7 June 2019). This programme of work built on a policy note issued in January 2019 which provided for two ‘pillars’ to be developed with a view to reaching a global consensus-based solution by the end of 2020. Pillar one provided for a new allocation of taxing rights through new nexus and profit allocation rules and pillar two, the ‘GloBE’ proposal, sought to introduce measures to ensure a minimum level of tax. In an attempt to reconcile differences of opinion, alongside the report to the G20 finance ministers, the OECD Secretariat has published a proposal for a ‘unified approach’ under pillar one (‘the proposal’, see bit.ly/2IBrnxH).

The proposal, out for consultation until 12 November, does not yet represent consensus among the 134 Inclusive Framework members. However, it is hoped that this will break the deadlock between the three competing pillar one approaches outlined in the January 2019 policy note and help move the negotiations forward. Pillar two has not been forgotten: a consultation will be published on this in November, and work continues in the background but, for now, the spotlight is on pillar one.

The proposal highlights the commonalities between the three proposals (which, you may recall, were focused around user participation, marketing intangibles and significant economic presence). More importantly, it seeks to bridge the gaps between them, acknowledging that without doing so it will not be possible to deliver a consensus solution within the specified timeframe. The theme of the entire paper is trying to find a solution that countries can agree on. This is a colossal undertaking, but the OECD is well-equipped for the task and intent on forging a way forward. The proposal emphasises that ‘the future of multilateral tax cooperation’, ‘the intense political pressure to tax highly digitalised MNEs’ and ‘fundamental features of the international tax system’ all hang in the balance. The proposal cautions that ‘the stakes are very high’.

Who is affected?

The focus of the proposal is on large consumer-facing businesses. One possibility for defining ‘large’ might be by reference to revenue thresholds, with the €750m country by country reporting global threshold cited as an option. The BEPS Action 13 report indicated that such a threshold would exclude approximately 85 to 90% of MNE groups (see bit.ly/1Iij6tW).

The concept of ‘consumer-facing’ businesses intentionally extends beyond big tech companies but rather looks more generally towards those enterprises likely to derive meaningful value from interaction with consumers in market jurisdictions. This does not mean that B2B businesses are out. Although the focus will certainly be on B2C businesses, where a B2B business involves sales of consumer products through intermediaries, this is likely to be brought into scope. However, the focus on consumers does mean that there will be certain sectors with less engagement with the market where this rationale does not apply. The proposal indicates that extractive industries and commodities businesses are likely to be carved out on this basis. Financial services may follow suit, but discussions on this continue.

A new nexus rule

One of the commonalities between the three original proposals was the need to move beyond nexus based on physical presence. A test proposed in the Programme of Work was whether a multinational has a ‘sustained and significant involvement in the economy of a market jurisdiction’. The proposal suggests that this would be largely based on sales, noting that the simplest way to operate such a nexus rule would be to define a revenue threshold (which could be adapted to the size of the market to ensure smaller economies can benefit) as the primary indicator of sustained and significant involvement in the market. Another possibility, floated in the OECD webcast held on 9 October, would be to look at a time threshold; for example, whether the business had more than one year of activity in the market (presumably a nod to the ‘sustained’ aspect of the new nexus rule).

The proposal makes a point of highlighting that the new nexus rule will be a standalone concept, separate from permanent establishment (PE) concepts, on the basis that there is no desire to disturb existing bilateral treaty provisions and in an attempt to limit any unintended spillover effects. However, regardless of whether drafted as a self-standing treaty provision or as an amendment to the PE concept, the interaction between the two rules will have to be carefully crafted to prevent entities being subject to double taxation. The OECD is alive to this: one of the ‘pending key questions’ still to be explored is how the existing mechanisms for eliminating double taxation under both domestic law and treaties could operate under the unified approach.

New profit allocation rules

Having determined there is a new taxing right that can apply to non-residents with no physical presence in a jurisdiction, a new rule must also be created to allocate profit to this new nexus concept, as traditional income allocation rules would allocate no profit to it, rendering it redundant! The proposal therefore seeks to create a new profit allocation rule and the OECD is clearly taking a pragmatic approach to this. This does not necessarily involve finding the fairest solution, or even the best or most logically pure, but the key is to find a solution that all jurisdictions will get behind.

To do this, the OECD has proposed an ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ approach. Richard Collier of the OECD has emphasised that there is no appetite to sweep away the arm’s length principle (the ALP), and the proposal advocates keeping the ALP where it works well, but then supplementing it with a formulaic approach around the pressure points where disputes are prone to arise. This recognises the level of dissatisfaction, especially amongst developing countries, around the current complexity of the ALP as a tool for determining residual profits and the need for a simpler, ‘administrable’ solution in order to reduce disputes and minimise compliance costs.

A three-tier approach

So, how would this work? The proposal involves a three-tier profit allocation mechanism consisting of:

Amount A represents the ‘new taxing right’. You start by identifying the total group profit (‘z’ in the diagram below). This is likely to be based on consolidated financial statements under GAAP or IFRS, although there are still questions around whether this should be separated by business line or region.

The next step is calculating the routine profit where activities are performed (‘x’). This could be determined in a number of ways. To the extent that there is a desire to preserve the ALP where it works well, arguably there is a role for this here, but a simplified approach would be to agree a fixed percentage to be deducted. A slightly more nuanced version would use different percentages for different industries. The use of proxies is intended to simplify the calculation of amount A; the proposal insists that this is not intended to alter the remuneration for routine activities as calculated under the existing transfer pricing framework. It does, however, indicate a move away from the ‘significant economic presence’ option, in that the unified approach only seeks to re-allocate non-routine profits, whereas the significant economic presence proposal looked at re-allocating both routine and non-routine profits.

The amount that is left after deducting the routine profit (‘y’, being z-x) would then be split between the portion that is attributable to market jurisdictions (‘w’) and the portion that is attributable to other factors, such as trade intangibles (‘v’). The former amount (‘w’) would then be allocated between the markets that meet the new nexus rules through a formula based on sales. This is effectively amount A, i.e. the deemed residual profit that is subject to the new taxing right (see diagram above).

Amounts B and C are not about the new taxing right. Rather, these refer back to a traditional nexus with the market jurisdiction. The idea is that activities in the market jurisdiction would still be taxable under existing rules, including the ALP and looking at the activities of any PE in the market jurisdiction. However, it is hoped that having a fixed return reflecting an assumed baseline activity, amount B, could reduce the number of disputes relating to distribution functions.

Amount C is said to be designed to provide a mechanism to ease disputes. It is intended to allow additional profit in excess of amount B where there are more functions in the market jurisdiction than is assumed in the baseline. Any such amount must be supported by the application of the ALP. Although the OECD claims this is there to address the certainty agenda, in some ways it detracts from the formulaic certainty provided by amount B by re-opening the door to the uncertainties in the ALP. Perhaps we should also be wary of amount C’s application of the ALP leading to the use of a ‘bright line’ test resonating with the US case of DHL Inc and Subsidiaries v Commissioner (TCM 1998/461) which sought to determine whether local advertising/marketing/promotion (AMP) expenditure exceeded some measure of normality, which has led to significant litigation, for example in India. Again, the OECD is braced for this kind of issue, indicating that ‘robust measures’ to resolve disputes and prevent double taxation form an important part of this proposal. The consultation document invites respondents to share their experiences of unilateral and multilateral APAs, ICAP as well as mandatory binding MAP arbitration. Effective dispute resolution (and prevention) mechanisms will be fundamental to the success of the proposal, not only in preventing double taxation as between amounts A, B and C, but also between the new taxing right and existing rules.

The proposal includes an example, illustrated in the box (below), which demonstrates that (i) each of amounts A, B and C, can arise in the jurisdiction where a group does have a taxable presence in the market jurisdiction and (ii) double taxation may arise as between the traditional taxing jurisdictions and the market jurisdictions in respect of amount A.

Implementation

Assuming the 134 members of the Inclusive Framework agree to this outline of the architecture for a unified approach to pillar one, how can it be achieved? Even though the new taxing right will be separate from the PE concept and so may not require changes to article 5 (permanent establishments) of the OECD Model Tax Convention, other changes to treaties, e.g. article 7 (business profits), will undoubtedly be required to allocate taxing rights over a non-resident’s business profits where there is no physical presence in the relevant jurisdiction. With the OECD of the view that changes to treaties would need to be ‘implemented simultaneously by all jurisdictions, to ensure a level playing field’, a second multilateral instrument (MLI 2.0?) seems inevitable.

Other thorny issues arise around enforcement and collection where amount A is assigned to an entity with no physical presence in a jurisdiction. Withholding tax is suggested as an option here. Another practical issue will be identifying which entity within the MNE group is treated as ‘owning’ the taxable profits in market jurisdictions under amount A and how would this interact with existing domestic and treaty relieving provisions.

Conclusion

There will be winners and losers under these proposals. The OECD report to finance ministers notes that pillar two would yield a ‘significant increase of corporate income tax revenue globally’ indicating that there will be a shift from income not being taxed to being taxed. This implies that there is still (despite the multitude of measures already introduced under BEPS) an issue with stateless income or with intangibles being held in tax havens. However, only a ‘modest’ increase in tax revenue is expected under pillar one. The shift here being from investment hubs (where analysis indicates there are high levels of residual profit) to market jurisdictions, particularly low and middle-income economies. However, the expectation is that larger market jurisdictions will benefit more in absolute terms. And this is crucial. There is an acknowledgement that there is no point pressing on with these proposals if the major players, such as the US and the EU will not agree. Pascal Saint-Amans, director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration has said that the US is on board and ‘that is the game-changer’.

Equally, with emerging economies and developing countries making up a large, and vocal, proportion of the Inclusive Framework, their interests cannot be ignored. This is why the proposal favours simplicity over fairness. The aim is to make the system simple to administer and the OECD’s pragmatic approach seems to be working. With the number of countries in the Inclusive Framework gradually rising, more and more countries are joining this attempt to reach global consensus.

There are, of course, a number of essential points that still need to be agreed, in terms of rates and thresholds and definitions. The Inclusive Framework members will be watching the impact assessments with a keen eye when it comes to fleshing out these points, particularly when it comes to setting rates, as these will be the crunch points that will make or break the proposals.

It has been suggested that the OECD proposals do not go far enough and that the OECD is ‘canonising gradualism’. Saint-Amans addressed these comments directly, indicating that this may indeed be what the OECD is doing given ‘we are not writing books for the shelves’. This is not an academic exercise looking at what the OECD thinks the world should do ‘in ideal circumstances’. Rather, his aim is to see how the rules can be changed so that ‘we have a better system, which is agreed by everybody and which changes things in practice’. As the saying goes, you can’t turn a tanker with a speedboat turn. And this is indeed a gargantuan tanker to turn. For some, it seems progress is not being made fast enough: the day after the OECD Secretariat’s proposal was published, Austria passed its unilateral digital advertising tax. It is measures like this that the OECD is striving to avoid. Asa Johansson, head of the OECD’s structural policies surveillance division, economics department, flagged that inaction by the OECD could lead to a further increase in tax uncertainty and a deterioration in the business and investment environment. Stabilising the system and improving certainty are the guiding principles behind the proposal.

And, whatever the critics may say, progress is being made on a grand scale. Huge shifts in thinking have already taken place. Formulary apportionment, previously rejected when floated in relation to the original BEPS project, is now front and centre of the proposals. The acceptance of nexus without physical presence marks a move towards destination-based tax, something discussed by economists in the 1990s but without ever gaining traction. And yet here we are. The tanker is turning.