While but a slip of a lad, statistically speaking, Rishi Sunak is very nearly the most prolific chancellor of the post-war era. Given Sunak’s sudden promotion a month ahead of his first Budget last year, only Hugh Dalton comes close to matching Sunak’s run-rate (so far) of one Budget for every 192 days in office. Ironically, Hugh Dalton’s career as chancellor was cut short when he inadvertently leaked his own Budget and had to resign; what in those days was a sacking offence, in our times has become standard practice. Arguably, if we include the numerous ‘mini-Budgets’ where Sunak has visited the Magic Money Tree over the past year, he outstrips even Mr Dalton. In any case, he will be due a second 2021 Budget in the Autumn.

The underlying message of the Budget was ‘trust me, I’m still a fiscal conservative’, with the chancellor stressing that his current predilection for shovelling public money out the door of 1 Horse Guards Road is just a temporary condition and that he will return to fiscal probity just as soon as he can. Where politicians have a reputation for claiming that cakes can be had at the same time as they are eaten, Sunak is promising as much cake as we need now, but pointing out that we will have to bake a new cake to replace it, and we will have to buy the ingredients for that when the time comes.

In policy terms that means a combination of:

Pretty much, though the chancellor was visibly thrilled to unveil an innovative ‘super-deduction’ which he pitched as a way of boosting business investment and unlocking cash reserves. For the rest, the measures he has taken are as trailed in the extensive pre-Budget briefing campaign. What gives them their newsworthiness is how they jar with the historical trends of UK tax policy (i.e. the first announced increase in the corporation tax headline rate since 1973).

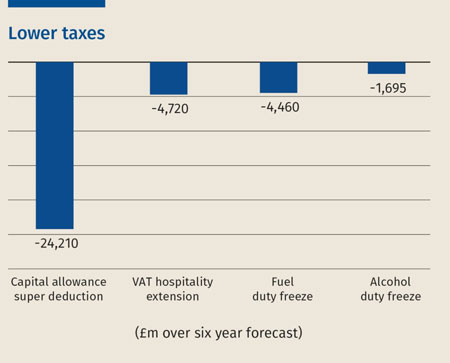

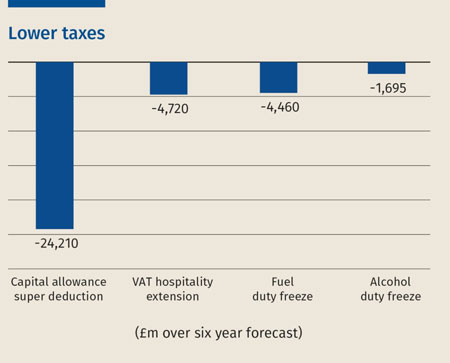

Essentially, the chancellor has recommitted to his flagship covid support measures. That sees employees and the self-employed continuing to receive support beyond March and, indeed, beyond the end of the current covid roadmap period. Similar extensions have been applied to the universal credit uplift, the business rates holiday and the reduced VAT rate for the hospitality sector. In other words, all those who are dependent on government cake, and were worried that it might be withdrawn at the end of this month can rest easy for a bit longer. Also, the chancellor has chosen to take the cake away in stages, with business rates, furlough (from the employer perspective), stamp duty land tax and VAT all being reduced in stages. This replaces one cliff edge with two smaller steps, tempering the risk for those falling on the wrong side of a critical date, but at the expense of an extra layer of complexity.

A theme in the Budget speech was the need to support regrowth and recovery. With that in mind, the chancellor unveiled a combination of additional grants (for example, for businesses reopening after the lockdown) and tax incentives.

The tax incentives include:

The grants will be timed to focus on sectors as they open up, with a particular focus on hospitality, personal care, culture and the arts.

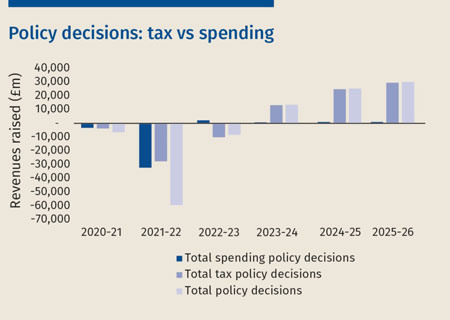

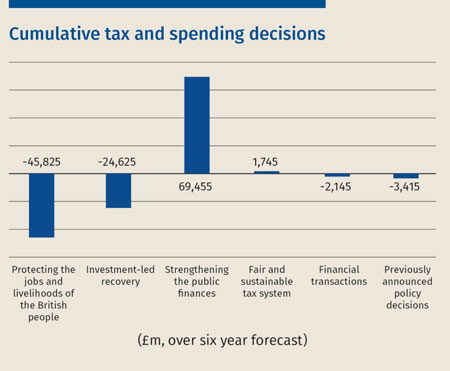

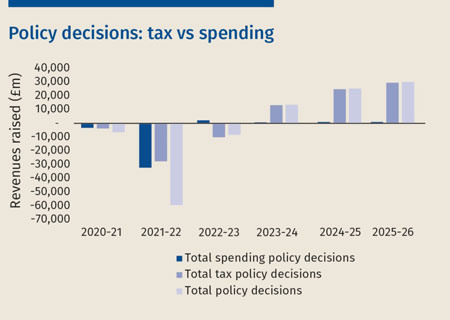

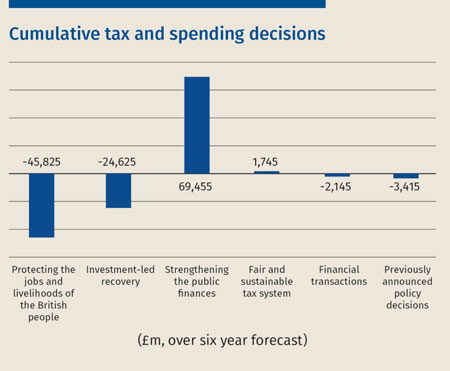

Well, it’s not cheap. By the time you add the spending announced on 3 March to the existing covid commitments, you won’t be getting much change out of £410bn. That is why the spending spree is followed by a period of tax increases. And as for this Budget itself and its six-year horizon, it was basically three years of spending (to the tune of approximately £70bn) followed by three years of tax rises (to generate broadly the same amount). Of course, the impact of the tax rises lasts beyond the six-year horizon, so the net effect is an increase in tax take each additional year by about £30bn, almost two thirds of the amount the chancellor was rumoured to be targeting.

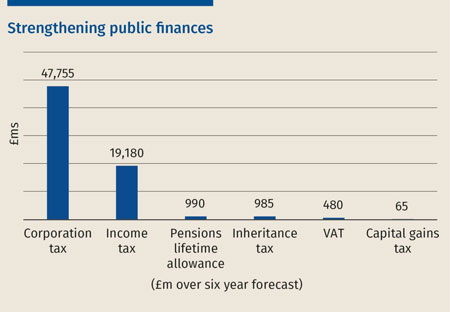

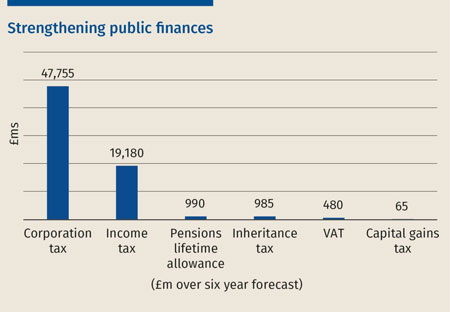

Indeed, it is not often you get to see an actual historical turning point, but that’s what we have here. After decades of reductions, the announcement that the headline corporation tax rate is going to increase from 19% to 25% in April 2023 comes with a jolt. You have to go all the way back to 1973 to see the last increase. The chancellor is now measuring the UK’s tax rate against the G7, which the UK will still be below, rather than the previous measure of choice, being the G20 with its lowest non-UK rate being 20%, or indeed the OECD, whose average the new UK rate will exceed.

To be clear, though, this isn’t quite an across-the-board tax increase for companies. The new 25% rate will apply to profits over £250,000, with the 19% rate applied for all those with profits at or below £50,000. In the middle, the chancellor is reintroducing marginal rate relief that was abolished in 2015 when the main corporation tax rate dropped to 20%, being the reduced rate at that time. Those with sufficiently long memories will realise that having the lower 19% rate taper away from £50,000 is much less generous than the taper that applied for the last 20 years and started at £300,000 and ran all the way up to £1,500,000. It seems that this chancellor believes that the low rate really should apply to small enterprises, rather than the small and medium-sized enterprises.

This is the largest tax rise in the Budget, generating north of £17bn per annum by the end of the Parliament, almost 60% of the total revenue raised.

One challenge of heralding an increase in the corporation tax rate is that capital investment can be stifled, as businesses wait to spend when they can get relief at the higher tax rate. This is perhaps the rationale for the super deduction, with 130% of relief at 19% being worth approximately the same as 100% of the relief at 25%. Of course, in practice, the ability to write off all the investment in one year, above the £1m limit of the annual investment allowance (which is due to drop to £200,000), is an incentive on its own, but this extra deduction removes the potential reason to wait.

Finally, in relation to the rate change, the extension of the loss carry back provisions to three years will of course mean that losses that might otherwise be set off against future profits taxed at the new 25% rate may well be used up against past profits suffering tax at 19%. Indeed, across the Budget scorecard, the Treasury predicts that this relaxation will actually raise £100m – not bad for a measure that is a giveaway.

On other taxes, Sunak has stuck to the ‘triple lock’ promise that he will not raise the rates of income tax, national insurance or VAT. Instead, he will be pausing the Coalition-inspired trend toward higher income tax personal allowances and also freezing thresholds in other taxes. He was too late to change the allowances for 2021/22, so the allowances will be frozen at that new level for four years, up to and including 2025/26. This creates what is known technically as ‘fiscal drag’ which allows people to drift more quickly into the higher tax brackets as their incomes or turnover rise.

This was a favourite of Gordon Brown’s and raises some significant revenue. Taken together, the effects of fiscal drag across income tax allowances, the VAT and IHT thresholds, the pensions lifetime allowance and the CGT annual exempt allowance will get the chancellor almost £22bn in additional revenue – and all without raising a single tax rate.

Whilst some of these might be justified on principle (rises in the level of personal allowance are not without controversy, as they do not help those on the lowest incomes who will already be below that level and having more people within the tax system can promote engagement), there has been speculation about whether other reliefs would be changed further. For example, the Office of Tax Simplification had suggested a radical reduction in the level of the CGT annual exempt amount and the UK’s VAT threshold remains the highest in Europe. At the moment, although these are not increasing, their current level seems to be protected.

The old concept of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ doesn’t have much currency in the current situation. To the extent that the chancellor’s largesse has saved the UK economy from complete collapse, everyone is a ‘winner’. To the extent that tax increases and fiscal drag are going to extract more cash from UK individuals and companies, everyone is a ‘loser’.

What is clear is that across a range of taxes the chancellor has left money on the table that he could otherwise have collected. To the extent that each untaxed pound is a ‘win’ there are winners here.

Only to the extent that collective angst prior to the Budget had built up an expectation that there could be moves to increase the CGT rate, the introduction of a new online sales tax and potential changes in taxation of the self-employed or personal service companies. These are not in this Budget but we could see them reappear in less than three weeks’ time.

Onwards to the Finance Bill, as usual. However, we do have an innovation this year in that a dedicated day of consultation has been ordained for 23 March. These consultations will be announced via a command paper with the somewhat less than snappy title of Tax policies and consultations (Spring 2021). This will include the publication of the report on the responses to the government’s consultation on business rates. In addition to the core business of dealing with an increasingly anachronistic tax (where the contribution different sectors make now bears little or no relation to their ability to pay), this may give us a clearer idea of where government thinking is headed on online sales taxes and on rebalancing the retail sector between brick-and-mortar and online. More likely, we will have to wait for the Autumn Budget for some real decisions. Other summaries of responses to consultation to be released will include the social investment tax relief extension.

This consultations day may also provide us with ideas of where the chancellor is expecting to find the additional funds that he needs to deal with the debts that have built up under covid. We have gone from the crash-bang-wallop of a Budget to the three-movement symphony of Budget, Finance Bill and consultations day.

The chancellor spoke in his Budget about being honest with the British people and this Budget was pretty much what he had led us to expect. Yes, it was harsher on businesses, with a 25% corporation tax rate being at the top end of (or beyond) expectations, but it also delivered on the support that he promised in the short term. The real question is now whether this is enough or whether we will hear more plans for tax increases on consultations day in three weeks’ time. Until then, we may have but half the picture.

While but a slip of a lad, statistically speaking, Rishi Sunak is very nearly the most prolific chancellor of the post-war era. Given Sunak’s sudden promotion a month ahead of his first Budget last year, only Hugh Dalton comes close to matching Sunak’s run-rate (so far) of one Budget for every 192 days in office. Ironically, Hugh Dalton’s career as chancellor was cut short when he inadvertently leaked his own Budget and had to resign; what in those days was a sacking offence, in our times has become standard practice. Arguably, if we include the numerous ‘mini-Budgets’ where Sunak has visited the Magic Money Tree over the past year, he outstrips even Mr Dalton. In any case, he will be due a second 2021 Budget in the Autumn.

The underlying message of the Budget was ‘trust me, I’m still a fiscal conservative’, with the chancellor stressing that his current predilection for shovelling public money out the door of 1 Horse Guards Road is just a temporary condition and that he will return to fiscal probity just as soon as he can. Where politicians have a reputation for claiming that cakes can be had at the same time as they are eaten, Sunak is promising as much cake as we need now, but pointing out that we will have to bake a new cake to replace it, and we will have to buy the ingredients for that when the time comes.

In policy terms that means a combination of:

Pretty much, though the chancellor was visibly thrilled to unveil an innovative ‘super-deduction’ which he pitched as a way of boosting business investment and unlocking cash reserves. For the rest, the measures he has taken are as trailed in the extensive pre-Budget briefing campaign. What gives them their newsworthiness is how they jar with the historical trends of UK tax policy (i.e. the first announced increase in the corporation tax headline rate since 1973).

Essentially, the chancellor has recommitted to his flagship covid support measures. That sees employees and the self-employed continuing to receive support beyond March and, indeed, beyond the end of the current covid roadmap period. Similar extensions have been applied to the universal credit uplift, the business rates holiday and the reduced VAT rate for the hospitality sector. In other words, all those who are dependent on government cake, and were worried that it might be withdrawn at the end of this month can rest easy for a bit longer. Also, the chancellor has chosen to take the cake away in stages, with business rates, furlough (from the employer perspective), stamp duty land tax and VAT all being reduced in stages. This replaces one cliff edge with two smaller steps, tempering the risk for those falling on the wrong side of a critical date, but at the expense of an extra layer of complexity.

A theme in the Budget speech was the need to support regrowth and recovery. With that in mind, the chancellor unveiled a combination of additional grants (for example, for businesses reopening after the lockdown) and tax incentives.

The tax incentives include:

The grants will be timed to focus on sectors as they open up, with a particular focus on hospitality, personal care, culture and the arts.

Well, it’s not cheap. By the time you add the spending announced on 3 March to the existing covid commitments, you won’t be getting much change out of £410bn. That is why the spending spree is followed by a period of tax increases. And as for this Budget itself and its six-year horizon, it was basically three years of spending (to the tune of approximately £70bn) followed by three years of tax rises (to generate broadly the same amount). Of course, the impact of the tax rises lasts beyond the six-year horizon, so the net effect is an increase in tax take each additional year by about £30bn, almost two thirds of the amount the chancellor was rumoured to be targeting.

Indeed, it is not often you get to see an actual historical turning point, but that’s what we have here. After decades of reductions, the announcement that the headline corporation tax rate is going to increase from 19% to 25% in April 2023 comes with a jolt. You have to go all the way back to 1973 to see the last increase. The chancellor is now measuring the UK’s tax rate against the G7, which the UK will still be below, rather than the previous measure of choice, being the G20 with its lowest non-UK rate being 20%, or indeed the OECD, whose average the new UK rate will exceed.

To be clear, though, this isn’t quite an across-the-board tax increase for companies. The new 25% rate will apply to profits over £250,000, with the 19% rate applied for all those with profits at or below £50,000. In the middle, the chancellor is reintroducing marginal rate relief that was abolished in 2015 when the main corporation tax rate dropped to 20%, being the reduced rate at that time. Those with sufficiently long memories will realise that having the lower 19% rate taper away from £50,000 is much less generous than the taper that applied for the last 20 years and started at £300,000 and ran all the way up to £1,500,000. It seems that this chancellor believes that the low rate really should apply to small enterprises, rather than the small and medium-sized enterprises.

This is the largest tax rise in the Budget, generating north of £17bn per annum by the end of the Parliament, almost 60% of the total revenue raised.

One challenge of heralding an increase in the corporation tax rate is that capital investment can be stifled, as businesses wait to spend when they can get relief at the higher tax rate. This is perhaps the rationale for the super deduction, with 130% of relief at 19% being worth approximately the same as 100% of the relief at 25%. Of course, in practice, the ability to write off all the investment in one year, above the £1m limit of the annual investment allowance (which is due to drop to £200,000), is an incentive on its own, but this extra deduction removes the potential reason to wait.

Finally, in relation to the rate change, the extension of the loss carry back provisions to three years will of course mean that losses that might otherwise be set off against future profits taxed at the new 25% rate may well be used up against past profits suffering tax at 19%. Indeed, across the Budget scorecard, the Treasury predicts that this relaxation will actually raise £100m – not bad for a measure that is a giveaway.

On other taxes, Sunak has stuck to the ‘triple lock’ promise that he will not raise the rates of income tax, national insurance or VAT. Instead, he will be pausing the Coalition-inspired trend toward higher income tax personal allowances and also freezing thresholds in other taxes. He was too late to change the allowances for 2021/22, so the allowances will be frozen at that new level for four years, up to and including 2025/26. This creates what is known technically as ‘fiscal drag’ which allows people to drift more quickly into the higher tax brackets as their incomes or turnover rise.

This was a favourite of Gordon Brown’s and raises some significant revenue. Taken together, the effects of fiscal drag across income tax allowances, the VAT and IHT thresholds, the pensions lifetime allowance and the CGT annual exempt allowance will get the chancellor almost £22bn in additional revenue – and all without raising a single tax rate.

Whilst some of these might be justified on principle (rises in the level of personal allowance are not without controversy, as they do not help those on the lowest incomes who will already be below that level and having more people within the tax system can promote engagement), there has been speculation about whether other reliefs would be changed further. For example, the Office of Tax Simplification had suggested a radical reduction in the level of the CGT annual exempt amount and the UK’s VAT threshold remains the highest in Europe. At the moment, although these are not increasing, their current level seems to be protected.

The old concept of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ doesn’t have much currency in the current situation. To the extent that the chancellor’s largesse has saved the UK economy from complete collapse, everyone is a ‘winner’. To the extent that tax increases and fiscal drag are going to extract more cash from UK individuals and companies, everyone is a ‘loser’.

What is clear is that across a range of taxes the chancellor has left money on the table that he could otherwise have collected. To the extent that each untaxed pound is a ‘win’ there are winners here.

Only to the extent that collective angst prior to the Budget had built up an expectation that there could be moves to increase the CGT rate, the introduction of a new online sales tax and potential changes in taxation of the self-employed or personal service companies. These are not in this Budget but we could see them reappear in less than three weeks’ time.

Onwards to the Finance Bill, as usual. However, we do have an innovation this year in that a dedicated day of consultation has been ordained for 23 March. These consultations will be announced via a command paper with the somewhat less than snappy title of Tax policies and consultations (Spring 2021). This will include the publication of the report on the responses to the government’s consultation on business rates. In addition to the core business of dealing with an increasingly anachronistic tax (where the contribution different sectors make now bears little or no relation to their ability to pay), this may give us a clearer idea of where government thinking is headed on online sales taxes and on rebalancing the retail sector between brick-and-mortar and online. More likely, we will have to wait for the Autumn Budget for some real decisions. Other summaries of responses to consultation to be released will include the social investment tax relief extension.

This consultations day may also provide us with ideas of where the chancellor is expecting to find the additional funds that he needs to deal with the debts that have built up under covid. We have gone from the crash-bang-wallop of a Budget to the three-movement symphony of Budget, Finance Bill and consultations day.

The chancellor spoke in his Budget about being honest with the British people and this Budget was pretty much what he had led us to expect. Yes, it was harsher on businesses, with a 25% corporation tax rate being at the top end of (or beyond) expectations, but it also delivered on the support that he promised in the short term. The real question is now whether this is enough or whether we will hear more plans for tax increases on consultations day in three weeks’ time. Until then, we may have but half the picture.