‘Unique’ is an almost uniquely overused word, when what is often meant is ‘unusual’ or ‘uncommon’. But this year’s Scottish Budget was indeed unique, revealed as it was for the first time prior to the UK Budget for the forthcoming tax year.

It was delivered, unexpectedly, by Kate Forbes MSP, due to circumstances into which we will go no further. But previous Scottish Budgets have also had unique elements, such as the first divergence from UK income tax rates and thresholds as compared to the rest of the UK; and the introduction within land and buildings transaction tax of various significant differences from its equivalents in the rest of the UK.

The timing of the Scottish Budget followed from the delay to the UK Budget caused by Brexit and the December election; and the wish of the Scottish government is that approval for the Scottish Budget is obtained by 5 March, nearly a week before the UK Budget is delivered on 11 March.

It has thus been necessary for the Scottish government to bring forward proposals based on estimates of what will be in the block grant (which will be crucial for spending plans), and presumably assumptions on what may or may not be done with non-devolved taxes (changes which could also affect the block grant and which in other years would certainly influence tax proposals for Scotland).

While the Scottish proposals are in no sense provisional for this reason (although see below), UK developments could lead to in-year adjustments and perhaps even revisiting the tax proposals (but this seems extremely unlikely).

After the genuinely unique aspects had been overcome, the Scottish Budget then followed a fairly familiar pattern. At least potentially, the divergence between income tax rates for Scottish taxpayers on earned and property income increased a little further, with higher earners set to pay a bit more (and lower earners a very small amount less), compared to the rest of the UK.

However, for the first time the extent of this divergence is not clear from the Scottish Budget, as that will depend entirely on what happens in the UK Budget on 11 March. There was a somewhat unexpected tweak (in other words, an increase) to land and buildings transaction tax, this time directed at one aspect of high value commercial property rather than residential property. The cans labelled aggregates levy, air departure tax and VAT assignment were kicked down the road again.

The Scottish Budget still seems to be an exercise dominated by announcements around projected spending, rather than raising the funds to finance that spending: in a crude measure, from the full Scottish Budget document, only 15 out of more than 250 pages are actually devoted to tax. At least to the same extent as last year, Budget proposals are subject to the vagaries of the Scottish government not having an absolute majority, although the Scottish Parliament was subjected to apocalyptic warnings of what would happen if the Budget was not passed as presented – with the truncated available timescale a factor in that potential apocalypse.

But past years have brought compromises and thus changes to original Scottish Budget proposals. So, announcements made on 6 February will not represent the end of the story for Scottish taxpayers for 2020/21. With that warning, further details on the Scottish Budget are as follows.

Income tax

In a partially devolved tax system, it is always worth a reminder that the most significant of taxes, income tax, is itself only partially devolved. Thus, the Scottish Parliament can set rates and thresholds as they affect only earned and property income; other rules, structures and reliefs (including the personal allowance), as well as the rates affecting dividend and other investment income, remain controlled by Westminster.

The same applies to that ‘income tax by any other name’, national insurance contributions. Scottish taxpayers will have to wait for the UK Budget as well as confirmation of these Budget proposals, before having a good idea of the tax inroads to their income for 2020/21.

With that said, the Scottish Budget proposals continue trends set in recent years, becoming slightly more progressive in economic terms in the process. The proposals maintained a structure of five rates for earned and property income above the personal allowance (that rate structure having been confirmed as intended to remain in place for the remainder of this Parliamentary term).

The personal allowance itself could be changed in the UK Budget, although it was stated after last year’s significant rise in that allowance that the level would remain unchanged for this tax year, before reverting to inflationary rises in subsequent years. That announcement is referred to in the Scottish Budget and the assumption is made that it will be confirmed in the March UK Budget. Of course, the announcement was made by a different chancellor, under a different prime minister and before both a general election and Brexit. Things change, to put it mildly.

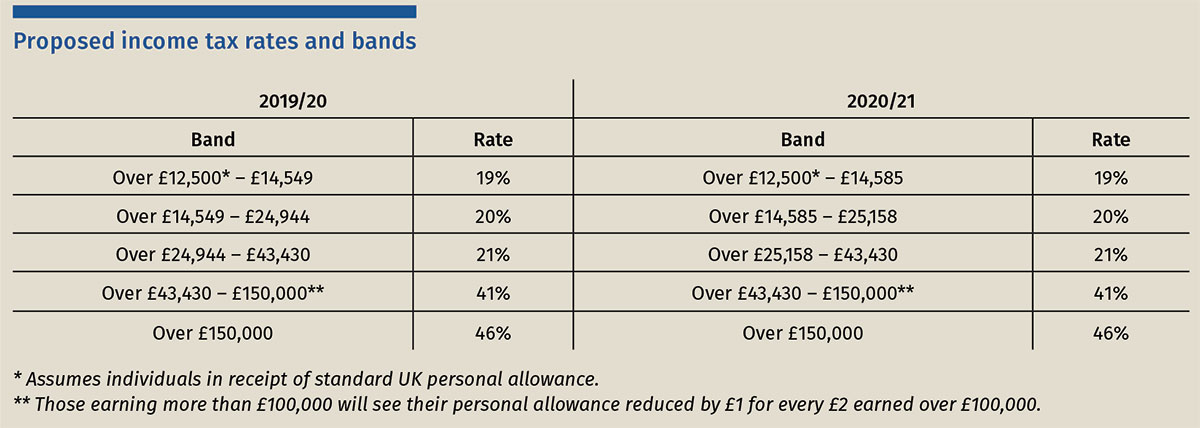

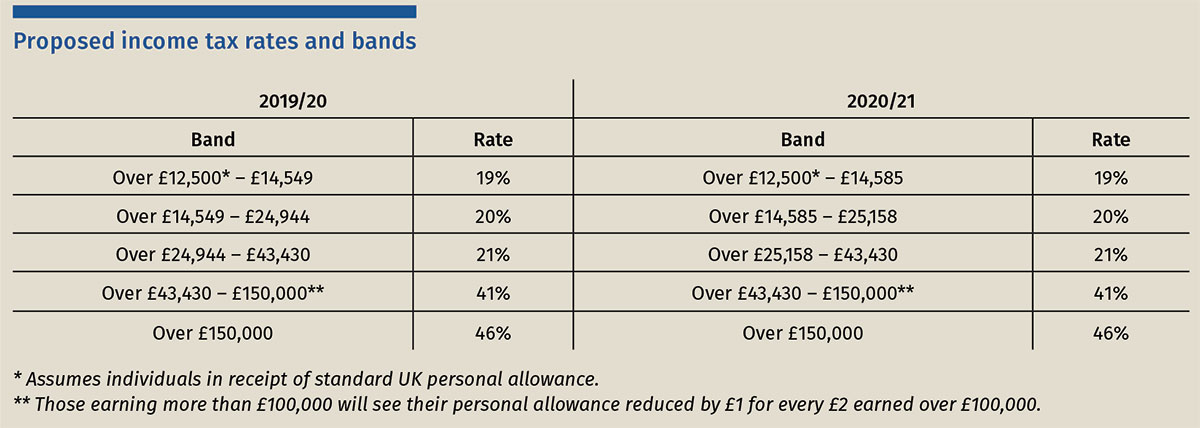

The proposals are for an inflationary rise in the first two rate bands for Scottish taxpayers, but a freeze in the two rate bands above that. (The Budget paperwork refers to an inflationary rise in the thresholds, but the very small numerical change in the first threshold confirms that the inflation percentage has been applied to the band of income subject to each rate.) See the table above for the proposed new rates and thresholds, compared with the current year’s equivalents.

Comparisons, it is sometimes said, are odious. Inevitably, new Scottish income tax rates are compared with previous ones; and with those in the rest of the UK. The first exercise is meaningful, as one is dealing with known facts; and the Budget papers confirm the inevitable with any rise to thresholds, that 90% of Scottish taxpayers would pay less Scottish income tax if their income were to remain unchanged between 2019/20 and 2020/21.

The second comparison made asserts that 56% of Scottish taxpayers will pay less than their counterparts elsewhere in the UK, with 44% paying more. But until the UK Budget is revealed, that comparison is provisional and may look, frankly, a little meaningless in a few weeks’ time.

There is a reference to a presumption that the UK higher rate threshold will also be frozen (at £50,000) for 2020/21, based on previous announcements. Putting aside the necessary uncertainty, the £21 less tax that the Scottish taxpayer earning £20,000 will pay looks a little scrawny compared to the £1,541 extra tax to be paid by the Scottish taxpayer earning £50,000, when both are compared to their rest of the UK counterparts.

The current structure of NICs brings a reduction in the applicable rate when earned income exceeds the UK higher rate threshold. That, combined with the fact that the Scottish higher rate is 41%, means that some Scottish taxpayers face total deductions of 53% on the slice of their income between the Scottish higher rate threshold and that set for the rest of the UK.

Another year with a frozen Scottish higher rate threshold may mean that the amount subject to that high marginal rate may rise again. If Scottish taxpayers can afford it, pension contributions and charitable donations from that slice of income will look particularly attractive.

Land and buildings transaction tax

From 7 February 2020, the rates of LBTT for non-residential leases will change.

For any lease with an effective date on or after 7 February 2020, a new 2% LBTT band will apply to the amount of any rental net present value (NPV) exceeding £2m. This represents a significant increase in the LBTT bill for commercial tenants compared to the old rates.

It also means that leases of Scottish commercial property will bear a higher tax cost than equivalent leases entered into in England and Northern Ireland where the higher rate kicks in at £5m (so a potential difference of up to £30,000 on a single lease).

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Tax Rates and Tax Bands) (Scotland) Amendment Order, SSI 2020/24, effecting the changes was laid before Parliament on 6 February after the Budget announcement.

Example 1: A ten year office lease with a (VAT inclusive) rent of £1m per year will have an LBTT NPV of £8,316,605. Under the old rates of LBTT, the tax would be £81,666. Under the new rates of LBTT, the tax will be £144,832. At the current SDLT rates, the tax is £114,382.

Transitional rules

There is a limited transitional rule, which shelters leases contracted for before 6 February 2020. Interestingly, the SSI appears silent on the nature of the contract (so there is no requirement for contracts to be unconditional, for example). There is also no reference to variations of contracts.

Example 2: Bernie owns two office units, which he intends to lease. For unit one he concluded an agreement for lease with Pete on 5 February 2020. For unit 2, he concluded an agreement for lease with Joe on 6 February 2020, after hearing the Budget announcement. Pete will be subject to LBTT at the old rates, but Joe will be subject to LBTT at the new rates.

However, while the transitional rule in the SSI is straightforward, the interaction with the LBTT/SDLT transitional rules are potentially quite complex and practitioners and taxpayers should be wary of potential hidden bear traps.

Example 3: Donald Jnr enters as a tenant under a commercial lease granted in 2012. He enters into missives for a lease variation to extend the term for a further five years on 7 February 2020. Under the LBTT/SDLT transitional rules, this is treated as the grant of a new lease for LBTT purposes and the extension will be subject to the new higher rates.

Example 4: Eric is a tenant under a commercial lease granted in 2016. He enters in to missives for a lease variation to extend the term for a further five years on 7 February 2020. For LBTT purposes, this is not treated as the grant of a new lease, and the change in term is just reflected in his three yearly returns. The old rates will continue to apply.

Example 5: Tiffany takes an assignation of a hotel lease from an operating company. The lease was originally granted in 2017 by the operating company’s parent, which owns the land. Group relief was claimed on the grant of the lease. The assignation of the lease is treated as the grant of a new lease to Tiffany by the assignor. Therefore, the new rates of LBTT will apply.

Other points to note

The higher rates should not affect existing leases which are already subject to LBTT and are required to submit three yearly/assignation/termination returns. Those leases will retain their original effective dates. Therefore, the old rates will continue to apply.

While residential leases are exempt from LBTT, practitioners should be wary of quasi-residential and mixed property leases and single transactions which involve a lease over six or more dwellings. Those are subject to LBTT and therefore, potentially, to the new rates.

New reliefs

The full Budget document referred to two reliefs, the introduction of which has been anticipated for some time. These are a relief for the ‘seeding’ of properties into a property authorised investment fund (PAIF) or co-owned authorised contractual scheme (CoACS); and a relief for when units in CoACS are exchanged. Uncertainty around Brexit was again blamed for the introduction of those reliefs having stalled. The Scottish government now plans to publish a consultation on draft legislation in 2020/21.

Additional dwelling supplement

While no changes were announced to this much resented impost, the following intriguing (if rather hesitant) promise was made: ‘following the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee’s consideration in 2019, the Scottish government is undertaking work to consider the range of views in relation to the operation of the ADS.’ There seems no prospect of slaughter for this cash cow, but perhaps some veterinary work is in line for its many ills.

Scottish landfill tax

Scottish landfill tax (SLfT) is a devolved tax on the disposal of waste to landfill, intended to serve as a financial incentive to minimise waste and create a more circular economy. Although not featured in the Budget speech, the fuller Budget paper does announce the Scottish government’s intention to increase both the standard and lower rates of SLfT in 2020/21 to £94.15 per tonne and £3 per tonne respectively. This increase ensures consistency with the planned changes to landfill tax rates in the rest of the UK. Following an earlier announcement that full enforcement of the ban on the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) should be delayed until 2025, the Scottish government is currently exploring the role that SLfT can play in reducing the practice and a further announcement can be expected in 2020/21.

Aggregates levy

From filling holes to making holes, the aggregates levy is a UK tax paid on the commercial exploitation of sand, gravel and rock. The Scottish Parliament was given legislative power to legislate for aggregates levy in 2016 but to date, no time line has been put forward as to when devolution will take place. The delay continues, pending the results of a comprehensive review of the levy currently being undertaken by the UK government, which follows the conclusion of long-standing litigation. The Scottish government confirms it will continue to work with the UK government and stakeholders in anticipation of the eventual devolution of the levy.

Air departure tax: no closer to taking off

Absent from the Scottish Budget statement and briefly mentioned in the Budget paper is the air passenger duty (APD); a tax devolved to the Scottish government by the Scotland Act 2016 which was due to be introduced with effect from April 2018. The Scottish government’s original intention was to reduce the rebranded ‘air departure tax’ by 50% before abolishing it completely, and also to introduce some exemptions for internal flights, known as the Highlands and Islands (H&I) exemption. The proposed reduction to 50%, which has since been scrapped due to contradiction with underlying environmental policy, was widely welcomed by the tourism bodies and the airline industry. However, a delay in introduction beyond April 2020 was announced on 23 April 2019, due to issues with the H&I exemption and this has been confirmed in the Scottish Budget 2020. In the meantime, APD remains in force in Scotland and is collected by the UK government.

VAT assignment

Roman statesman and lawyer Cicero once claimed that ‘brevity is the best recommendation of speech’. With that in mind, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Byzantine topic of VAT assignment did not feature in the Budget statement given by Kate Forbes MSP. Instead, for the second year in a row, announcements regarding VAT assignment were relegated to the Scottish government’s Budget paper.

What, you may ask, is VAT assignment? The Scotland Act 2016 provides for 10 pence of the standard rate of VAT and 2.5 pence of the reduced rate to be assigned to the Scottish government. The block grant will be reduced accordingly. Notably, there will be no ability to influence the rate of VAT.

VAT assignment remains in a transitional phase where VAT revenue is forecast and calculated, but it has no impact on the Scottish government’s budget.

Once both the Scottish and UK governments are happy that the assignment methodology works properly, the assignment of VAT receipts to Scotland will begin in earnest. At present, work to finalise the model which sets out that assignment methodology is ongoing. It will be discussed through the Joint Exchequer Committee.

Tax legislation process

Procedures for legislative changes to the Scottish tax system have been subject to criticism and a perceived need for a more systematic approach. Although not part of the Scottish Budget as such, the opportunity was taken to publish the interim report of the Devolved Taxes Legislation Working Group, which was established following the final report of the Budget Process Review Group in June 2017.

The working group’s report invites consultation on a number of matters, including the case for a new legislative process for tax, which might involve a regular Finance or Tax Bill; and current or adjusted use of secondary legislation. Responses are invited by 20 March.

‘Unique’ is an almost uniquely overused word, when what is often meant is ‘unusual’ or ‘uncommon’. But this year’s Scottish Budget was indeed unique, revealed as it was for the first time prior to the UK Budget for the forthcoming tax year.

It was delivered, unexpectedly, by Kate Forbes MSP, due to circumstances into which we will go no further. But previous Scottish Budgets have also had unique elements, such as the first divergence from UK income tax rates and thresholds as compared to the rest of the UK; and the introduction within land and buildings transaction tax of various significant differences from its equivalents in the rest of the UK.

The timing of the Scottish Budget followed from the delay to the UK Budget caused by Brexit and the December election; and the wish of the Scottish government is that approval for the Scottish Budget is obtained by 5 March, nearly a week before the UK Budget is delivered on 11 March.

It has thus been necessary for the Scottish government to bring forward proposals based on estimates of what will be in the block grant (which will be crucial for spending plans), and presumably assumptions on what may or may not be done with non-devolved taxes (changes which could also affect the block grant and which in other years would certainly influence tax proposals for Scotland).

While the Scottish proposals are in no sense provisional for this reason (although see below), UK developments could lead to in-year adjustments and perhaps even revisiting the tax proposals (but this seems extremely unlikely).

After the genuinely unique aspects had been overcome, the Scottish Budget then followed a fairly familiar pattern. At least potentially, the divergence between income tax rates for Scottish taxpayers on earned and property income increased a little further, with higher earners set to pay a bit more (and lower earners a very small amount less), compared to the rest of the UK.

However, for the first time the extent of this divergence is not clear from the Scottish Budget, as that will depend entirely on what happens in the UK Budget on 11 March. There was a somewhat unexpected tweak (in other words, an increase) to land and buildings transaction tax, this time directed at one aspect of high value commercial property rather than residential property. The cans labelled aggregates levy, air departure tax and VAT assignment were kicked down the road again.

The Scottish Budget still seems to be an exercise dominated by announcements around projected spending, rather than raising the funds to finance that spending: in a crude measure, from the full Scottish Budget document, only 15 out of more than 250 pages are actually devoted to tax. At least to the same extent as last year, Budget proposals are subject to the vagaries of the Scottish government not having an absolute majority, although the Scottish Parliament was subjected to apocalyptic warnings of what would happen if the Budget was not passed as presented – with the truncated available timescale a factor in that potential apocalypse.

But past years have brought compromises and thus changes to original Scottish Budget proposals. So, announcements made on 6 February will not represent the end of the story for Scottish taxpayers for 2020/21. With that warning, further details on the Scottish Budget are as follows.

Income tax

In a partially devolved tax system, it is always worth a reminder that the most significant of taxes, income tax, is itself only partially devolved. Thus, the Scottish Parliament can set rates and thresholds as they affect only earned and property income; other rules, structures and reliefs (including the personal allowance), as well as the rates affecting dividend and other investment income, remain controlled by Westminster.

The same applies to that ‘income tax by any other name’, national insurance contributions. Scottish taxpayers will have to wait for the UK Budget as well as confirmation of these Budget proposals, before having a good idea of the tax inroads to their income for 2020/21.

With that said, the Scottish Budget proposals continue trends set in recent years, becoming slightly more progressive in economic terms in the process. The proposals maintained a structure of five rates for earned and property income above the personal allowance (that rate structure having been confirmed as intended to remain in place for the remainder of this Parliamentary term).

The personal allowance itself could be changed in the UK Budget, although it was stated after last year’s significant rise in that allowance that the level would remain unchanged for this tax year, before reverting to inflationary rises in subsequent years. That announcement is referred to in the Scottish Budget and the assumption is made that it will be confirmed in the March UK Budget. Of course, the announcement was made by a different chancellor, under a different prime minister and before both a general election and Brexit. Things change, to put it mildly.

The proposals are for an inflationary rise in the first two rate bands for Scottish taxpayers, but a freeze in the two rate bands above that. (The Budget paperwork refers to an inflationary rise in the thresholds, but the very small numerical change in the first threshold confirms that the inflation percentage has been applied to the band of income subject to each rate.) See the table above for the proposed new rates and thresholds, compared with the current year’s equivalents.

Comparisons, it is sometimes said, are odious. Inevitably, new Scottish income tax rates are compared with previous ones; and with those in the rest of the UK. The first exercise is meaningful, as one is dealing with known facts; and the Budget papers confirm the inevitable with any rise to thresholds, that 90% of Scottish taxpayers would pay less Scottish income tax if their income were to remain unchanged between 2019/20 and 2020/21.

The second comparison made asserts that 56% of Scottish taxpayers will pay less than their counterparts elsewhere in the UK, with 44% paying more. But until the UK Budget is revealed, that comparison is provisional and may look, frankly, a little meaningless in a few weeks’ time.

There is a reference to a presumption that the UK higher rate threshold will also be frozen (at £50,000) for 2020/21, based on previous announcements. Putting aside the necessary uncertainty, the £21 less tax that the Scottish taxpayer earning £20,000 will pay looks a little scrawny compared to the £1,541 extra tax to be paid by the Scottish taxpayer earning £50,000, when both are compared to their rest of the UK counterparts.

The current structure of NICs brings a reduction in the applicable rate when earned income exceeds the UK higher rate threshold. That, combined with the fact that the Scottish higher rate is 41%, means that some Scottish taxpayers face total deductions of 53% on the slice of their income between the Scottish higher rate threshold and that set for the rest of the UK.

Another year with a frozen Scottish higher rate threshold may mean that the amount subject to that high marginal rate may rise again. If Scottish taxpayers can afford it, pension contributions and charitable donations from that slice of income will look particularly attractive.

Land and buildings transaction tax

From 7 February 2020, the rates of LBTT for non-residential leases will change.

For any lease with an effective date on or after 7 February 2020, a new 2% LBTT band will apply to the amount of any rental net present value (NPV) exceeding £2m. This represents a significant increase in the LBTT bill for commercial tenants compared to the old rates.

It also means that leases of Scottish commercial property will bear a higher tax cost than equivalent leases entered into in England and Northern Ireland where the higher rate kicks in at £5m (so a potential difference of up to £30,000 on a single lease).

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Tax Rates and Tax Bands) (Scotland) Amendment Order, SSI 2020/24, effecting the changes was laid before Parliament on 6 February after the Budget announcement.

Example 1: A ten year office lease with a (VAT inclusive) rent of £1m per year will have an LBTT NPV of £8,316,605. Under the old rates of LBTT, the tax would be £81,666. Under the new rates of LBTT, the tax will be £144,832. At the current SDLT rates, the tax is £114,382.

Transitional rules

There is a limited transitional rule, which shelters leases contracted for before 6 February 2020. Interestingly, the SSI appears silent on the nature of the contract (so there is no requirement for contracts to be unconditional, for example). There is also no reference to variations of contracts.

Example 2: Bernie owns two office units, which he intends to lease. For unit one he concluded an agreement for lease with Pete on 5 February 2020. For unit 2, he concluded an agreement for lease with Joe on 6 February 2020, after hearing the Budget announcement. Pete will be subject to LBTT at the old rates, but Joe will be subject to LBTT at the new rates.

However, while the transitional rule in the SSI is straightforward, the interaction with the LBTT/SDLT transitional rules are potentially quite complex and practitioners and taxpayers should be wary of potential hidden bear traps.

Example 3: Donald Jnr enters as a tenant under a commercial lease granted in 2012. He enters into missives for a lease variation to extend the term for a further five years on 7 February 2020. Under the LBTT/SDLT transitional rules, this is treated as the grant of a new lease for LBTT purposes and the extension will be subject to the new higher rates.

Example 4: Eric is a tenant under a commercial lease granted in 2016. He enters in to missives for a lease variation to extend the term for a further five years on 7 February 2020. For LBTT purposes, this is not treated as the grant of a new lease, and the change in term is just reflected in his three yearly returns. The old rates will continue to apply.

Example 5: Tiffany takes an assignation of a hotel lease from an operating company. The lease was originally granted in 2017 by the operating company’s parent, which owns the land. Group relief was claimed on the grant of the lease. The assignation of the lease is treated as the grant of a new lease to Tiffany by the assignor. Therefore, the new rates of LBTT will apply.

Other points to note

The higher rates should not affect existing leases which are already subject to LBTT and are required to submit three yearly/assignation/termination returns. Those leases will retain their original effective dates. Therefore, the old rates will continue to apply.

While residential leases are exempt from LBTT, practitioners should be wary of quasi-residential and mixed property leases and single transactions which involve a lease over six or more dwellings. Those are subject to LBTT and therefore, potentially, to the new rates.

New reliefs

The full Budget document referred to two reliefs, the introduction of which has been anticipated for some time. These are a relief for the ‘seeding’ of properties into a property authorised investment fund (PAIF) or co-owned authorised contractual scheme (CoACS); and a relief for when units in CoACS are exchanged. Uncertainty around Brexit was again blamed for the introduction of those reliefs having stalled. The Scottish government now plans to publish a consultation on draft legislation in 2020/21.

Additional dwelling supplement

While no changes were announced to this much resented impost, the following intriguing (if rather hesitant) promise was made: ‘following the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee’s consideration in 2019, the Scottish government is undertaking work to consider the range of views in relation to the operation of the ADS.’ There seems no prospect of slaughter for this cash cow, but perhaps some veterinary work is in line for its many ills.

Scottish landfill tax

Scottish landfill tax (SLfT) is a devolved tax on the disposal of waste to landfill, intended to serve as a financial incentive to minimise waste and create a more circular economy. Although not featured in the Budget speech, the fuller Budget paper does announce the Scottish government’s intention to increase both the standard and lower rates of SLfT in 2020/21 to £94.15 per tonne and £3 per tonne respectively. This increase ensures consistency with the planned changes to landfill tax rates in the rest of the UK. Following an earlier announcement that full enforcement of the ban on the landfilling of biodegradable municipal waste (BMW) should be delayed until 2025, the Scottish government is currently exploring the role that SLfT can play in reducing the practice and a further announcement can be expected in 2020/21.

Aggregates levy

From filling holes to making holes, the aggregates levy is a UK tax paid on the commercial exploitation of sand, gravel and rock. The Scottish Parliament was given legislative power to legislate for aggregates levy in 2016 but to date, no time line has been put forward as to when devolution will take place. The delay continues, pending the results of a comprehensive review of the levy currently being undertaken by the UK government, which follows the conclusion of long-standing litigation. The Scottish government confirms it will continue to work with the UK government and stakeholders in anticipation of the eventual devolution of the levy.

Air departure tax: no closer to taking off

Absent from the Scottish Budget statement and briefly mentioned in the Budget paper is the air passenger duty (APD); a tax devolved to the Scottish government by the Scotland Act 2016 which was due to be introduced with effect from April 2018. The Scottish government’s original intention was to reduce the rebranded ‘air departure tax’ by 50% before abolishing it completely, and also to introduce some exemptions for internal flights, known as the Highlands and Islands (H&I) exemption. The proposed reduction to 50%, which has since been scrapped due to contradiction with underlying environmental policy, was widely welcomed by the tourism bodies and the airline industry. However, a delay in introduction beyond April 2020 was announced on 23 April 2019, due to issues with the H&I exemption and this has been confirmed in the Scottish Budget 2020. In the meantime, APD remains in force in Scotland and is collected by the UK government.

VAT assignment

Roman statesman and lawyer Cicero once claimed that ‘brevity is the best recommendation of speech’. With that in mind, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Byzantine topic of VAT assignment did not feature in the Budget statement given by Kate Forbes MSP. Instead, for the second year in a row, announcements regarding VAT assignment were relegated to the Scottish government’s Budget paper.

What, you may ask, is VAT assignment? The Scotland Act 2016 provides for 10 pence of the standard rate of VAT and 2.5 pence of the reduced rate to be assigned to the Scottish government. The block grant will be reduced accordingly. Notably, there will be no ability to influence the rate of VAT.

VAT assignment remains in a transitional phase where VAT revenue is forecast and calculated, but it has no impact on the Scottish government’s budget.

Once both the Scottish and UK governments are happy that the assignment methodology works properly, the assignment of VAT receipts to Scotland will begin in earnest. At present, work to finalise the model which sets out that assignment methodology is ongoing. It will be discussed through the Joint Exchequer Committee.

Tax legislation process

Procedures for legislative changes to the Scottish tax system have been subject to criticism and a perceived need for a more systematic approach. Although not part of the Scottish Budget as such, the opportunity was taken to publish the interim report of the Devolved Taxes Legislation Working Group, which was established following the final report of the Budget Process Review Group in June 2017.

The working group’s report invites consultation on a number of matters, including the case for a new legislative process for tax, which might involve a regular Finance or Tax Bill; and current or adjusted use of secondary legislation. Responses are invited by 20 March.