We all pay stamp duty when we buy a house. But there’s a well-known trick: have your house owned by a company – a special purpose company that does absolutely nothing else (often called ‘enveloping’). Then, when you come to sell, you sell the shares in the company, and the buyer pays no stamp duty.

This had been going on forever, but became widely publicised in the early 2010s. In a sane world, the ‘loophole’ would’ve been closed by simply applying stamp duty to the sale of the shares. But for obscure reasons (in large part EU law complications around the Capital Duties Directive), the loophole was left open, but anyone exploiting it and buying residential real estate held by a company was stung with an annual tax: the annual tax on enveloped dwellings (ATED) introduced in 2013.

The idea was that the prospect of paying an annual tax would put people off enveloping altogether – ATED wouldn’t raise much money, but would increase stamp duty revenues. That didn’t quite happen – and ATED, the tax that nobody was supposed to pay, ended up raising over £100m each year, with around 5,000 residential properties still held in envelopes (including about 100 properties worth more than £20m).

Why are people stubbornly keeping their homes enveloped, despite ATED? Sometimes it is to hide the identity of owners (whether because of security concerns or more malign reasons) – although this will now be harder to do. Sometimes it is simply because ATED is way too small to undo the stamp duty saving from enveloping. The tax applies in bands like this:

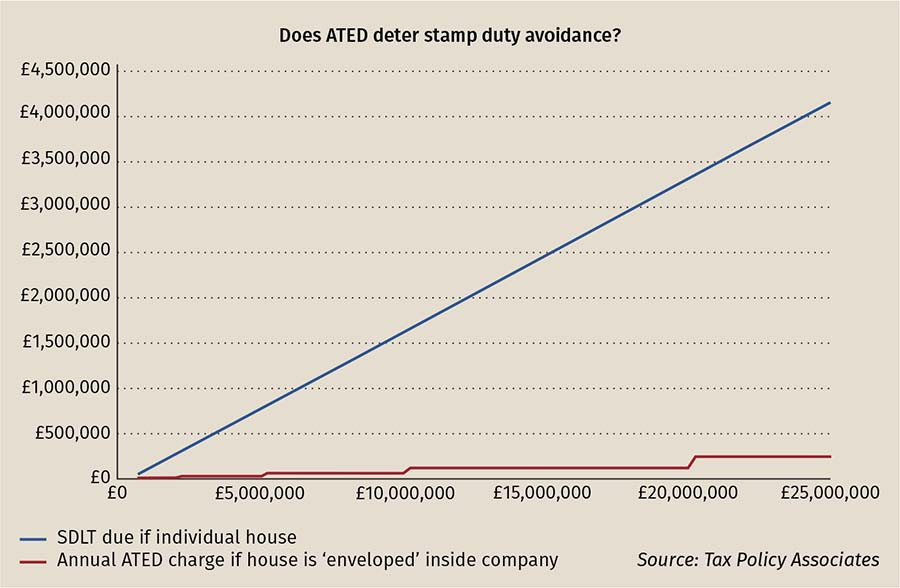

This means that the gap between stamp duty and ATED is fairly dramatic, particularly at the high end (see the chart below).

In other words:

So ATED is too low to do the job it was designed to do. The enveloping ‘loophole’ is still worthwhile, and the more expensive the property, the more worthwhile it is.

The sensible solution is to close the loophole properly, and make stamp duty apply on the sale of companies holding residential real estate (just as I think we should for companies purchasing commercial real estate). But if we don’t want to do that (or want a stopgap while we finalise how we’re going to properly sort things out), let’s just increase ATED.

ATED currently raises £111m, and the average ATED break-even point is about 20 years. So if we triple the rate, we can expect to raise around £200m – much of which would be in increased stamp duty revenues, as people ‘de-envelope’. That would reduce the average ATED break-even point to around six years, which seems a more realistic timeframe for ownership of high-value real estate. We’re not quite done: increasing ATED at each of the existing bands doesn’t solve the problem of ATED ‘capping-out’ for very high-value properties – here, the obvious solution is for ATED to continue to apply at each additional £5m of value.

This seems a simple, fair and straightforward-to-implement way to raise £200m. How could any chancellor resist such a proposition? This decision has the potential to significantly reduce the evidential burden on HMRC in proving ‘significant distortion of competition’ where two activities are identical or similar from the point of view of the consumer, and also shows that the general approach to fiscal neutrality in terms of competition also applies to questions of public authority VAT exemption.

We all pay stamp duty when we buy a house. But there’s a well-known trick: have your house owned by a company – a special purpose company that does absolutely nothing else (often called ‘enveloping’). Then, when you come to sell, you sell the shares in the company, and the buyer pays no stamp duty.

This had been going on forever, but became widely publicised in the early 2010s. In a sane world, the ‘loophole’ would’ve been closed by simply applying stamp duty to the sale of the shares. But for obscure reasons (in large part EU law complications around the Capital Duties Directive), the loophole was left open, but anyone exploiting it and buying residential real estate held by a company was stung with an annual tax: the annual tax on enveloped dwellings (ATED) introduced in 2013.

The idea was that the prospect of paying an annual tax would put people off enveloping altogether – ATED wouldn’t raise much money, but would increase stamp duty revenues. That didn’t quite happen – and ATED, the tax that nobody was supposed to pay, ended up raising over £100m each year, with around 5,000 residential properties still held in envelopes (including about 100 properties worth more than £20m).

Why are people stubbornly keeping their homes enveloped, despite ATED? Sometimes it is to hide the identity of owners (whether because of security concerns or more malign reasons) – although this will now be harder to do. Sometimes it is simply because ATED is way too small to undo the stamp duty saving from enveloping. The tax applies in bands like this:

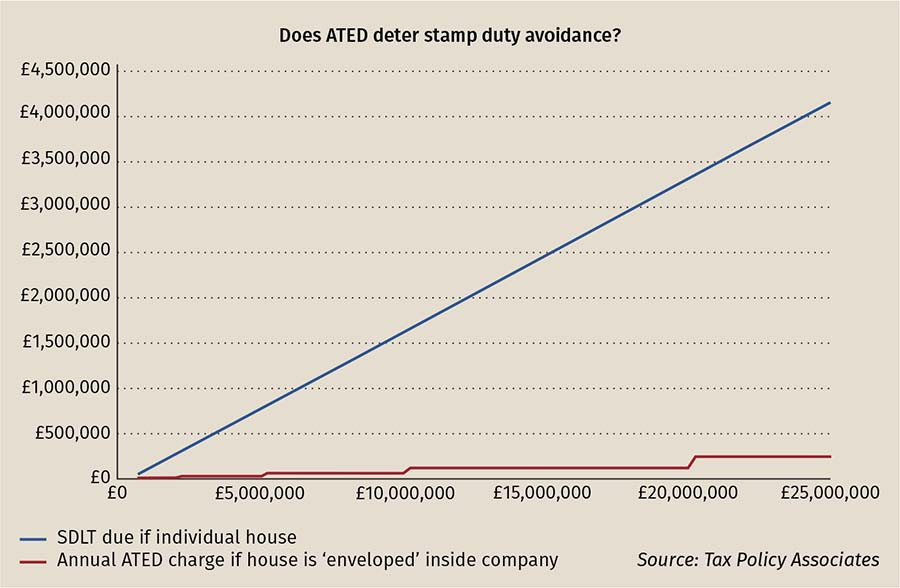

This means that the gap between stamp duty and ATED is fairly dramatic, particularly at the high end (see the chart below).

In other words:

So ATED is too low to do the job it was designed to do. The enveloping ‘loophole’ is still worthwhile, and the more expensive the property, the more worthwhile it is.

The sensible solution is to close the loophole properly, and make stamp duty apply on the sale of companies holding residential real estate (just as I think we should for companies purchasing commercial real estate). But if we don’t want to do that (or want a stopgap while we finalise how we’re going to properly sort things out), let’s just increase ATED.

ATED currently raises £111m, and the average ATED break-even point is about 20 years. So if we triple the rate, we can expect to raise around £200m – much of which would be in increased stamp duty revenues, as people ‘de-envelope’. That would reduce the average ATED break-even point to around six years, which seems a more realistic timeframe for ownership of high-value real estate. We’re not quite done: increasing ATED at each of the existing bands doesn’t solve the problem of ATED ‘capping-out’ for very high-value properties – here, the obvious solution is for ATED to continue to apply at each additional £5m of value.

This seems a simple, fair and straightforward-to-implement way to raise £200m. How could any chancellor resist such a proposition? This decision has the potential to significantly reduce the evidential burden on HMRC in proving ‘significant distortion of competition’ where two activities are identical or similar from the point of view of the consumer, and also shows that the general approach to fiscal neutrality in terms of competition also applies to questions of public authority VAT exemption.