SPEED READ On 22 June it was announced that HMRC would consult on the merits of introducing a GAAR. Although it is clear that no commitment has yet been made to a GAAR, such rules are increasingly common overseas. The overseas experience does not, however, bode well for any UK GAAR and there is no one country we can look to to provide a blueprint of a well functioning regime to emulate. The overriding issue is one of uncertainty and complexity. While a pre-clearance process should help with this, it can be seen from many countries that a badly designed or operated clearance regime can prove worthless.

Anneli Collins looks at how GAARs have developed in several overseas countries and the lessons to learn from this

Much has been written recently on the prospect of the introduction of a general anti avoidance rule (GAAR) in the UK. The Liberal Democrats made it clear before the General Election that they favoured a ‘general anti-avoidance principle’ and the ‘emergency’ Budget on 22 June announced that HMRC will consult informally on the merits of introducing a GAAR.

This subject was last fully debated in the UK in 1998 when the then Inland Revenue proposed wording for a GAAR but, after consultation, the idea was eventually dismissed as a step too far.

However, since then GAARs have become an increasingly common theme overseas with many countries either introducing them or amending their existing rules to give them more bite. This article looks at what has happened in practice in some of these countries.

Looking overseas and, indeed, the debate around the 1998 proposals, it is clear that GAARs can be structured in many different ways. These range from the simple ones seen in mainland Europe (where they are really a simple abuse of law principle such that transactions are caught if they are entered into solely to claim a tax benefit) to the very complex rules found in, for example, South Africa (where the details run to many pages and there are numerous factual conditions to consider). In this article, we examine a few countries which give a flavour to the range of options available.

Canada

Let’s start with one of the oldest GAARs on which many countries have modelled their own.

A GAAR was first introduced in Canada in 1987 and there are three tests that need to be met for it to apply:

If the GAAR applies, the transactions are recast ‘as are reasonable in the circumstances’. Generally, this results in the effective elimination of the tax benefit but no penalties are imposed due to specific case law on this point.

So these are the rules but what issues have taxpayers experienced on their practical application?

The issue in almost all the GAAR court cases is whether there is a ‘clear policy’ and whether that policy has been abused/misused. Usually, ‘tax benefit’ and ‘avoidance transaction’ are conceded and the debate centres around what is the policy in question.

The GAAR has been considered in around 30 cases and even now there is still uncertainty since the application of the rules by the courts and authorities has been inconsistent and sometimes contradictory. As a result there has been much negative push back with some taxpayers saying that their task of deciding what is and what is not acceptable is almost impossible.

To try and help with this problem the authorities have published a number of information circulars which give examples of what they see as abusive tax avoidance but, like HMRC guidance in the UK, this does not have statutory force and in practice these circulars are seen only as highlighting areas where a dispute is likely to ensue.

It is often said that a GAAR should go hand in hand with an advance clearance procedure to give taxpayers certainty and Canada does have such a procedure. However, taxpayers often choose not to apply for a ruling.

This is because there is the perception that, where the authorities disagree with the approach taken, they will not issue a ruling even where they would ultimately have difficulty in successfully applying the GAAR. It is not uncommon for taxpayers to feel that all they have done by applying for the ruling is invite an audit.

GAAR rulings are therefore generally only requested where:

So overall certainty, or rather lack of it, was the biggest issue for taxpayers when the GAAR was introduced and this remains the case 23 years after it entered into force. HMRC would be well advised to look at the Canadian experience to help understand the many problems that can arise with a GAAR.

Spain

Spain is an interesting example of a European-style GAAR which has been in place in one form or other since the 1960s. The Spanish GAAR includes two doctrines: the conflict and the sham doctrines.

Under the conflict doctrine, the Spanish Tax Authorities (STA) can challenge inappropriate transactions that lack a sound business reason and are aimed at achieving a tax benefit only. Under the sham doctrine, the STA may recharacterise a transaction by disregarding the sham arrangements and taking into account instead the deal that the taxpayer actually really wanted to enter into.

The STA look at what is happening in the market on a regular basis and then issue internal instructions to tax auditors explaining certain transactions they consider constitute tax avoidance and setting out the grounds on which they could be challenged. The STA also publish a list of the sectors and types of transactions they will be focusing on in a given period.

This gives some guidance to the way the GAAR will be applied.

However, despite this, the GAAR has undoubtedly created uncertainty and may also have influenced the views of overseas investors. For example, at the end of the 1990s, the Spanish holding company regime was very popular and was being actively promoted by the Spanish authorities but its implementation under certain fact patterns is now being attacked under the GAAR to the extent that the US Chamber of Commerce is trying to lobby the STA to stop the tax audits of US investors.

A key learning point from the Spanish example is that, if unchecked, the actions of the tax authorities implementing a GAAR can have a negative impact on a country’s attractiveness to overseas investors.

New Zealand

New Zealand is worth a brief mention because this is a country where the legislation enacting the GAAR is relatively simple but, because it is so general, this again creates much uncertainty. It has not been easy for taxpayers or the authorities to develop clear principles from the case law that exists as this is generally very fact specific.

The GAAR applies where tax avoidance is one 'more than merely incidental' purpose or effect of the transaction. Applying this rule has been the most difficult aspect of the GAAR. In essence, the many approaches in the cases taken amount to asking whether there is an acceptable commercial purpose or whether the scheme and purpose of the Act justifies the tax effect. The latter approach remains uncertain with the most recent case under appeal to New Zealand’s (highest) Supreme Court.

New Zealand operates a binding rulings regime but, to date, the process has been time consuming to pursue and responses from the tax authorities have been slow meaning the rulings regime has not been as useful as it could be. However, the process is being improved to make rulings more timely. Developments in this regard in New Zealand will be worth watching as an effective pre-clearance system can be such an important factor in a GAAR regime.

Other countries

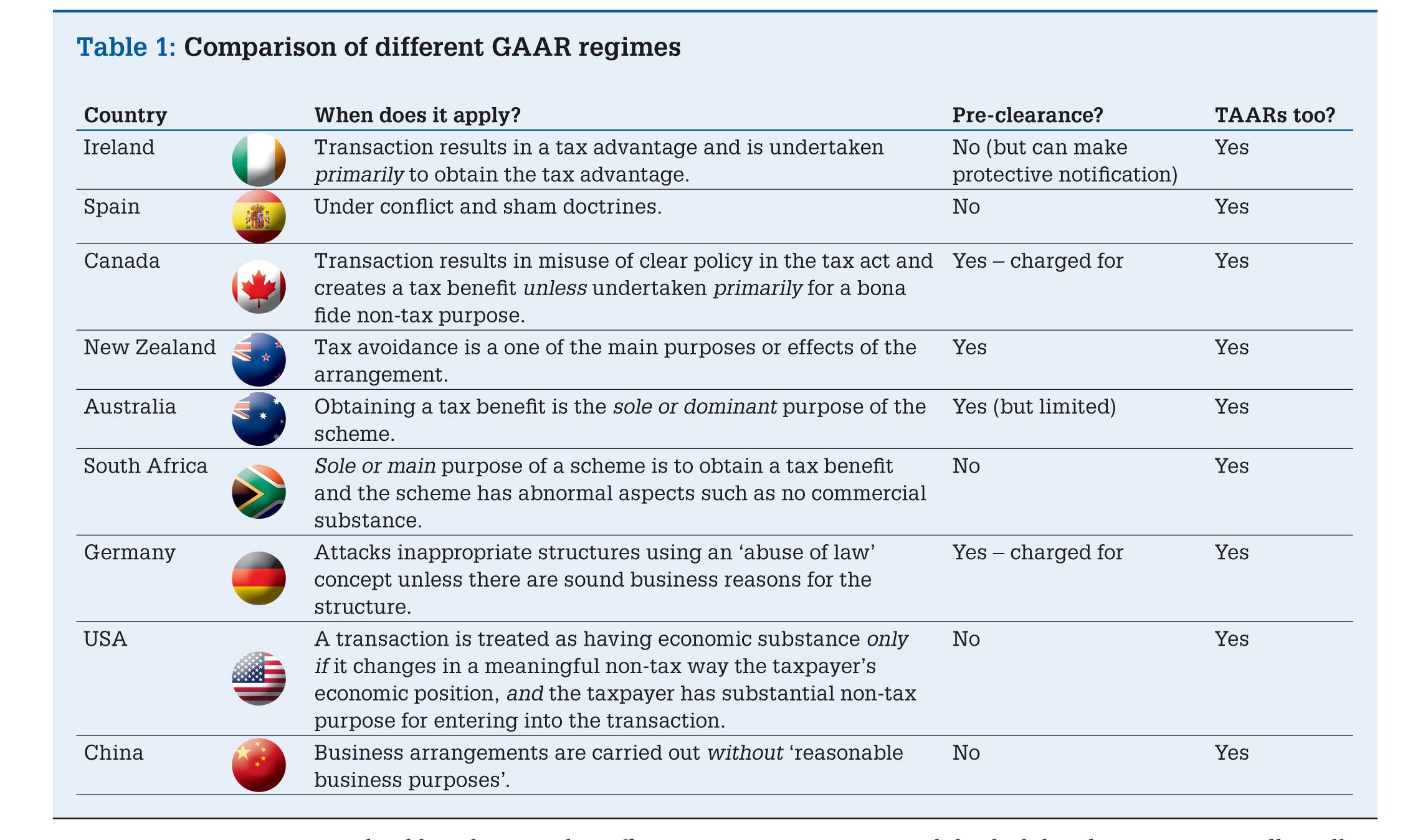

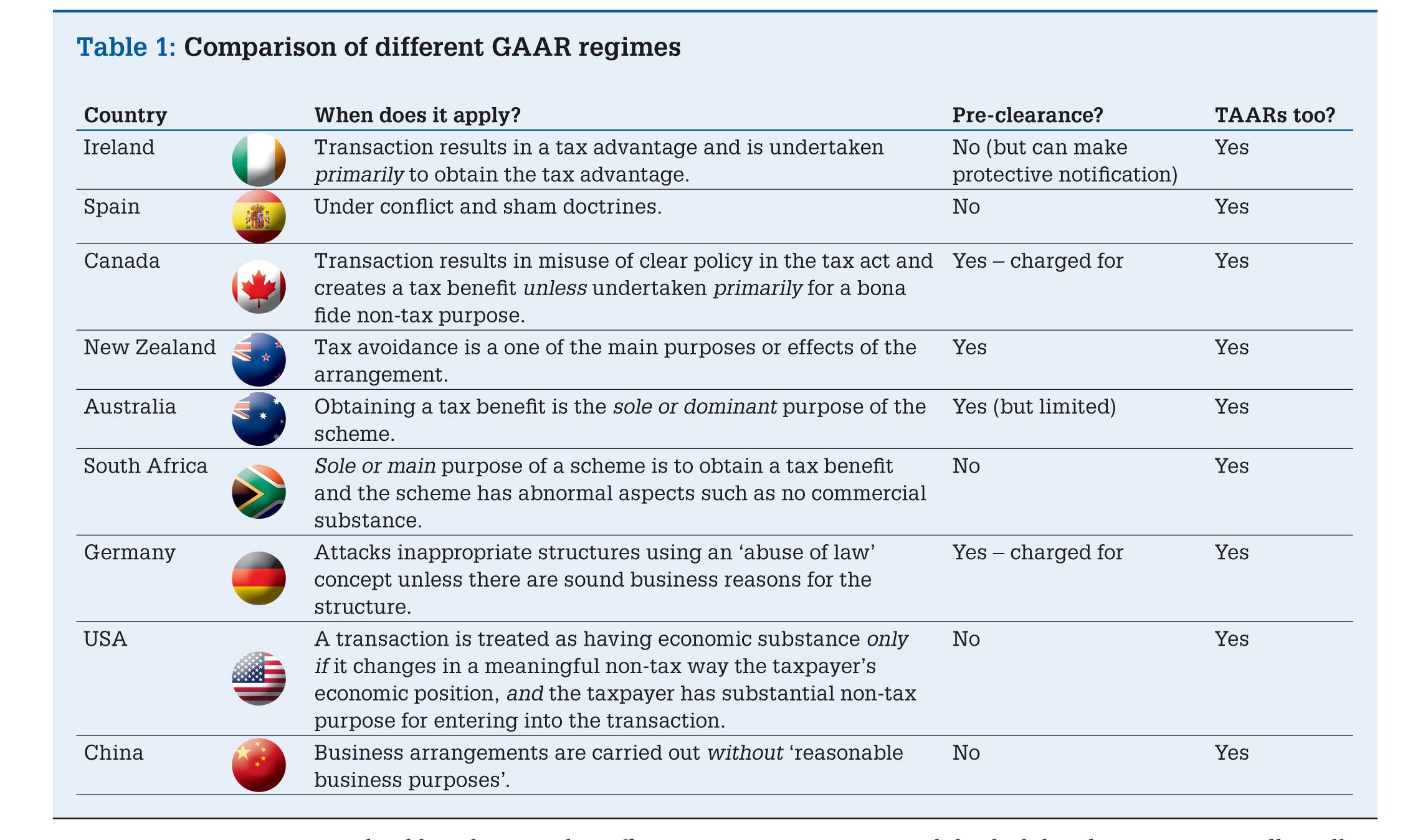

Table 1 sets out a few characteristics of GAAR regimes in these and some other key countries.

One aspect that has not been discussed above is the interaction of targeted anti-avoidance rules (TAARs) with a GAAR. In the UK, we currently have numerous TAARs and as one of the coalition Government’s stated aims is to simplify the tax system a GAAR brings with it the potential to remove many of these. However, it is notable that TAARs are generally maintained overseas when a GAAR is introduced.

In Germany, the general view is that the GAAR can only apply where there is no TAAR but in most countries the GAAR is an additional hurdle to face even where a TAAR has not been breached. However, in many such countries, the GAAR is set at a higher level and only applies where tax avoidance is the sole or primary purpose of the planning. This is, of course, a much higher watershed than the common UK phraseology of ‘main or one of the main purposes’.

It does not bode well…

The overseas experience does not bode well for any UK GAAR and there is no one country we can look to to provide a blueprint of a well functioning regime to emulate. By far the biggest issue HMRC will need to face is how to avoid creating massive uncertainty for taxpayers. While a pre-clearance process should help with this it can be seen from many countries that a badly designed or operated clearance regime can prove worthless.

.jpg)

Anneli Collins is a Tax Partner with KPMG in the UK. She is Head of Tax Policy and also Head of M&A Tax for KPMG Europe. Anneli has over 15 years' experience advising companies on large international transactions and cross border structuring. Email: anneli.collins@kpmg.co.uk; tel: 020 7694 3403.

SPEED READ On 22 June it was announced that HMRC would consult on the merits of introducing a GAAR. Although it is clear that no commitment has yet been made to a GAAR, such rules are increasingly common overseas. The overseas experience does not, however, bode well for any UK GAAR and there is no one country we can look to to provide a blueprint of a well functioning regime to emulate. The overriding issue is one of uncertainty and complexity. While a pre-clearance process should help with this, it can be seen from many countries that a badly designed or operated clearance regime can prove worthless.

Anneli Collins looks at how GAARs have developed in several overseas countries and the lessons to learn from this

Much has been written recently on the prospect of the introduction of a general anti avoidance rule (GAAR) in the UK. The Liberal Democrats made it clear before the General Election that they favoured a ‘general anti-avoidance principle’ and the ‘emergency’ Budget on 22 June announced that HMRC will consult informally on the merits of introducing a GAAR.

This subject was last fully debated in the UK in 1998 when the then Inland Revenue proposed wording for a GAAR but, after consultation, the idea was eventually dismissed as a step too far.

However, since then GAARs have become an increasingly common theme overseas with many countries either introducing them or amending their existing rules to give them more bite. This article looks at what has happened in practice in some of these countries.

Looking overseas and, indeed, the debate around the 1998 proposals, it is clear that GAARs can be structured in many different ways. These range from the simple ones seen in mainland Europe (where they are really a simple abuse of law principle such that transactions are caught if they are entered into solely to claim a tax benefit) to the very complex rules found in, for example, South Africa (where the details run to many pages and there are numerous factual conditions to consider). In this article, we examine a few countries which give a flavour to the range of options available.

Canada

Let’s start with one of the oldest GAARs on which many countries have modelled their own.

A GAAR was first introduced in Canada in 1987 and there are three tests that need to be met for it to apply:

If the GAAR applies, the transactions are recast ‘as are reasonable in the circumstances’. Generally, this results in the effective elimination of the tax benefit but no penalties are imposed due to specific case law on this point.

So these are the rules but what issues have taxpayers experienced on their practical application?

The issue in almost all the GAAR court cases is whether there is a ‘clear policy’ and whether that policy has been abused/misused. Usually, ‘tax benefit’ and ‘avoidance transaction’ are conceded and the debate centres around what is the policy in question.

The GAAR has been considered in around 30 cases and even now there is still uncertainty since the application of the rules by the courts and authorities has been inconsistent and sometimes contradictory. As a result there has been much negative push back with some taxpayers saying that their task of deciding what is and what is not acceptable is almost impossible.

To try and help with this problem the authorities have published a number of information circulars which give examples of what they see as abusive tax avoidance but, like HMRC guidance in the UK, this does not have statutory force and in practice these circulars are seen only as highlighting areas where a dispute is likely to ensue.

It is often said that a GAAR should go hand in hand with an advance clearance procedure to give taxpayers certainty and Canada does have such a procedure. However, taxpayers often choose not to apply for a ruling.

This is because there is the perception that, where the authorities disagree with the approach taken, they will not issue a ruling even where they would ultimately have difficulty in successfully applying the GAAR. It is not uncommon for taxpayers to feel that all they have done by applying for the ruling is invite an audit.

GAAR rulings are therefore generally only requested where:

So overall certainty, or rather lack of it, was the biggest issue for taxpayers when the GAAR was introduced and this remains the case 23 years after it entered into force. HMRC would be well advised to look at the Canadian experience to help understand the many problems that can arise with a GAAR.

Spain

Spain is an interesting example of a European-style GAAR which has been in place in one form or other since the 1960s. The Spanish GAAR includes two doctrines: the conflict and the sham doctrines.

Under the conflict doctrine, the Spanish Tax Authorities (STA) can challenge inappropriate transactions that lack a sound business reason and are aimed at achieving a tax benefit only. Under the sham doctrine, the STA may recharacterise a transaction by disregarding the sham arrangements and taking into account instead the deal that the taxpayer actually really wanted to enter into.

The STA look at what is happening in the market on a regular basis and then issue internal instructions to tax auditors explaining certain transactions they consider constitute tax avoidance and setting out the grounds on which they could be challenged. The STA also publish a list of the sectors and types of transactions they will be focusing on in a given period.

This gives some guidance to the way the GAAR will be applied.

However, despite this, the GAAR has undoubtedly created uncertainty and may also have influenced the views of overseas investors. For example, at the end of the 1990s, the Spanish holding company regime was very popular and was being actively promoted by the Spanish authorities but its implementation under certain fact patterns is now being attacked under the GAAR to the extent that the US Chamber of Commerce is trying to lobby the STA to stop the tax audits of US investors.

A key learning point from the Spanish example is that, if unchecked, the actions of the tax authorities implementing a GAAR can have a negative impact on a country’s attractiveness to overseas investors.

New Zealand

New Zealand is worth a brief mention because this is a country where the legislation enacting the GAAR is relatively simple but, because it is so general, this again creates much uncertainty. It has not been easy for taxpayers or the authorities to develop clear principles from the case law that exists as this is generally very fact specific.

The GAAR applies where tax avoidance is one 'more than merely incidental' purpose or effect of the transaction. Applying this rule has been the most difficult aspect of the GAAR. In essence, the many approaches in the cases taken amount to asking whether there is an acceptable commercial purpose or whether the scheme and purpose of the Act justifies the tax effect. The latter approach remains uncertain with the most recent case under appeal to New Zealand’s (highest) Supreme Court.

New Zealand operates a binding rulings regime but, to date, the process has been time consuming to pursue and responses from the tax authorities have been slow meaning the rulings regime has not been as useful as it could be. However, the process is being improved to make rulings more timely. Developments in this regard in New Zealand will be worth watching as an effective pre-clearance system can be such an important factor in a GAAR regime.

Other countries

Table 1 sets out a few characteristics of GAAR regimes in these and some other key countries.

One aspect that has not been discussed above is the interaction of targeted anti-avoidance rules (TAARs) with a GAAR. In the UK, we currently have numerous TAARs and as one of the coalition Government’s stated aims is to simplify the tax system a GAAR brings with it the potential to remove many of these. However, it is notable that TAARs are generally maintained overseas when a GAAR is introduced.

In Germany, the general view is that the GAAR can only apply where there is no TAAR but in most countries the GAAR is an additional hurdle to face even where a TAAR has not been breached. However, in many such countries, the GAAR is set at a higher level and only applies where tax avoidance is the sole or primary purpose of the planning. This is, of course, a much higher watershed than the common UK phraseology of ‘main or one of the main purposes’.

It does not bode well…

The overseas experience does not bode well for any UK GAAR and there is no one country we can look to to provide a blueprint of a well functioning regime to emulate. By far the biggest issue HMRC will need to face is how to avoid creating massive uncertainty for taxpayers. While a pre-clearance process should help with this it can be seen from many countries that a badly designed or operated clearance regime can prove worthless.

.jpg)

Anneli Collins is a Tax Partner with KPMG in the UK. She is Head of Tax Policy and also Head of M&A Tax for KPMG Europe. Anneli has over 15 years' experience advising companies on large international transactions and cross border structuring. Email: anneli.collins@kpmg.co.uk; tel: 020 7694 3403.