In 2013 the then director of public prosecutions, Keir Starmer (as he was then), stated that the aim of the CPS was to increase prosecutions for tax evasion five-fold from a 2010 baseline.

Fieldfisher has tracked (and reported on) HMRC’s progress ever since. We doubted then whether that arbitrary aim was achievable and also whether it was necessary. It has not been achieved, and events suggest it was not necessary.

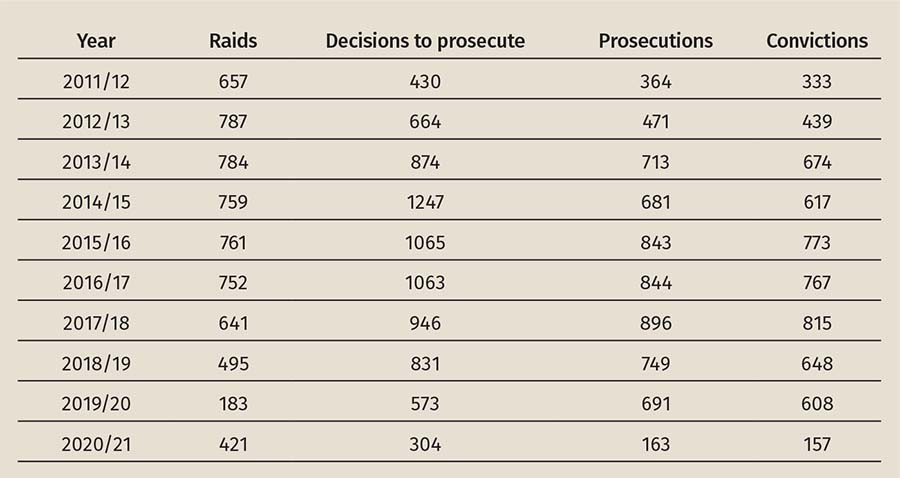

There are a number of figures that reveal the extent of HMRC’s criminal investigations activity, and the extent of its success (or failure): search warrants executed by HMRC (raids); decisions by the CPS to charge for tax offences (‘decisions to prosecute’); individuals prosecuted (‘prosecutions’); and convictions for tax offences in the courts (‘convictions’).

We have obtained, by way of a request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000, figures for 2020/21 using these definitions (these figures exclude tax credits offences). See the table below.

Raids

We believe the increase in raids for the 2020/21 figure from 2019/20 is a result of HMRC resuming normal compliance activity after its suspension due to the pandemic.

Decisions to prosecute

As expected, the number of decisions to prosecute has fallen. While this is partly a consequence of a covid-19 driven decrease in raids in the previous two years, it also reflects a change in HMRC’s behaviour. There has been a declining trend seen in the number of raids, and HMRC has reduced its focus from gathering evidence through raids as a precursor to prosecution for tax evasion.

Prosecutions and convictions

With a reduction in raids and decisions to prosecute, the number of prosecutions plunged 76%. Unsurprisingly the number of convictions also nosedived. However, 96% of prosecutions resulted in a conviction, which is impressively high. HMRC and the CPS are to be commended for focusing their resources on bringing to trial high quality cases with a realistic prospect of conviction.

Change in rhetoric and change in approach

We noted in 2020 signs of HMRC reducing its focus on gathering evidence through raids as a precursor to prosecution for tax evasion. Over the past year there appears to have been a further shift in tone by HMRC. In particular, in December 2021, HMRC published a policy paper on its approach to tax fraud.

In brief, this paper sets out when HMRC would expect to utilise its criminal investigation powers.

Firstly, serious fraud involving large losses or organised crime groups. We agree it’s clearly important societally to target the most pernicious forms of tax evasion.

Secondly, to send a strong deterrent message and reassure the honest majority there is a level playing field. We agree there’s a role for HMRC to play in targeting specific business sectors or customer groups where tax fraud is prevalent.

Thirdly, when HMRC’s civil powers aren’t enough to uncover the truth or recover the tax that is at stake. This may sound more menacing than it is. HMRC does use covert surveillance. But, as a former inspector of taxes, I know that there are quite rigorous internal procedures to be followed to authorise such covert surveillance.

Finally, the policy paper states that HMRC focus is ‘reaching the right outcome for the UK, rather than chasing arbitrary targets for arrests and prosecutions’.

To put it another way, the aims stated by the DPP in 2013 have been quietly abandoned. We think that’s the right thing to do. Criminal cases are very expensive and very time consuming, so it’s only right that HMRC use them selectively and focus on the most harmful, complex and sophisticated frauds.

What we can also derive from the above, however, is that if a taxpayer is the subject of a raid by HMRC, they are in serious trouble because the chances of a decision to prosecute, prosecution and conviction resulting from the raid are all extremely high.

In 2013 the then director of public prosecutions, Keir Starmer (as he was then), stated that the aim of the CPS was to increase prosecutions for tax evasion five-fold from a 2010 baseline.

Fieldfisher has tracked (and reported on) HMRC’s progress ever since. We doubted then whether that arbitrary aim was achievable and also whether it was necessary. It has not been achieved, and events suggest it was not necessary.

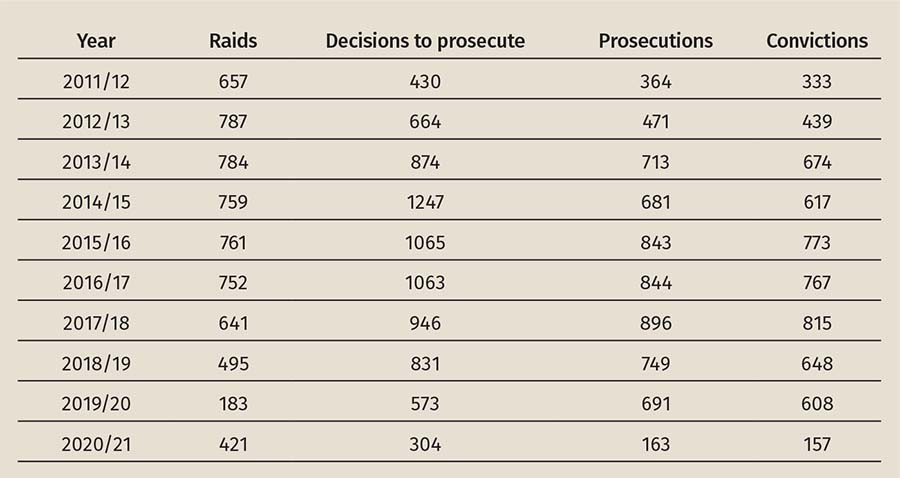

There are a number of figures that reveal the extent of HMRC’s criminal investigations activity, and the extent of its success (or failure): search warrants executed by HMRC (raids); decisions by the CPS to charge for tax offences (‘decisions to prosecute’); individuals prosecuted (‘prosecutions’); and convictions for tax offences in the courts (‘convictions’).

We have obtained, by way of a request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000, figures for 2020/21 using these definitions (these figures exclude tax credits offences). See the table below.

Raids

We believe the increase in raids for the 2020/21 figure from 2019/20 is a result of HMRC resuming normal compliance activity after its suspension due to the pandemic.

Decisions to prosecute

As expected, the number of decisions to prosecute has fallen. While this is partly a consequence of a covid-19 driven decrease in raids in the previous two years, it also reflects a change in HMRC’s behaviour. There has been a declining trend seen in the number of raids, and HMRC has reduced its focus from gathering evidence through raids as a precursor to prosecution for tax evasion.

Prosecutions and convictions

With a reduction in raids and decisions to prosecute, the number of prosecutions plunged 76%. Unsurprisingly the number of convictions also nosedived. However, 96% of prosecutions resulted in a conviction, which is impressively high. HMRC and the CPS are to be commended for focusing their resources on bringing to trial high quality cases with a realistic prospect of conviction.

Change in rhetoric and change in approach

We noted in 2020 signs of HMRC reducing its focus on gathering evidence through raids as a precursor to prosecution for tax evasion. Over the past year there appears to have been a further shift in tone by HMRC. In particular, in December 2021, HMRC published a policy paper on its approach to tax fraud.

In brief, this paper sets out when HMRC would expect to utilise its criminal investigation powers.

Firstly, serious fraud involving large losses or organised crime groups. We agree it’s clearly important societally to target the most pernicious forms of tax evasion.

Secondly, to send a strong deterrent message and reassure the honest majority there is a level playing field. We agree there’s a role for HMRC to play in targeting specific business sectors or customer groups where tax fraud is prevalent.

Thirdly, when HMRC’s civil powers aren’t enough to uncover the truth or recover the tax that is at stake. This may sound more menacing than it is. HMRC does use covert surveillance. But, as a former inspector of taxes, I know that there are quite rigorous internal procedures to be followed to authorise such covert surveillance.

Finally, the policy paper states that HMRC focus is ‘reaching the right outcome for the UK, rather than chasing arbitrary targets for arrests and prosecutions’.

To put it another way, the aims stated by the DPP in 2013 have been quietly abandoned. We think that’s the right thing to do. Criminal cases are very expensive and very time consuming, so it’s only right that HMRC use them selectively and focus on the most harmful, complex and sophisticated frauds.

What we can also derive from the above, however, is that if a taxpayer is the subject of a raid by HMRC, they are in serious trouble because the chances of a decision to prosecute, prosecution and conviction resulting from the raid are all extremely high.