I make no apology for returning to the subject of tax after covid, after my early remarks in April 2020 and again in October. The Treasury Select Committee published its report on this topic on 1 March, and on 23 March we have the novel experience of ‘tax day’ when we are told we will see ‘a range of important but less high profile measures’.

It will be very disappointing if those consultations do not set out a roadmap for the direction of tax policy, over this life of this government and perhaps beyond. Business constantly says that what it needs is certainty in order to make investment decisions, and the Treasury Select Committee commented in its report that: ‘We believe that a tax strategy setting out what the government wants to achieve from the tax system and identifying high level objectives would have much merit.’ As someone who first proposed the idea of a roadmap to the Blair government in 1997, I would warmly welcome the government publishing, and regularly updating, its strategic objectives for the tax system.

A key area which is ripe for reform is the taxation of income from work. This is far from being a new topic, but a range of different factors may mean that now is the time to start on the path to fundamental change. As I said in my April 2020 article: ‘The need to design separate [covid support] schemes for the employed and self-employed, and the significant gap for owner-managed companies, highlights that business income in the UK is taxed very differently depending on precisely how it is received.’ The IFS has been saying this for some time, since the Mirrlees report of 2011 if not before, and in February 2021 Stuart Adam and Helen Miller published a detailed report titled Taxing work and investment across legal forms: pathways to well-designed taxes, which Judith Freedman referred to in her recent article in which she asked ‘does employment status matter for tax?’

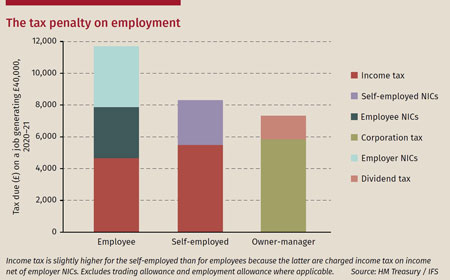

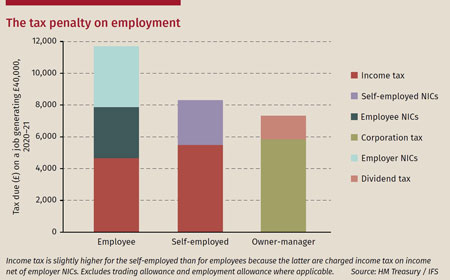

The Treasury Committee report has an excellent chapter on this topic, which highlights that the underlying issue is not really taxation but national insurance contributions (NICs). As the chart below shows, the total tax and NICs burden for a job generating £40,000 is almost £12,000 for an employee, which is £3,300 more than for a self-employed individual and £4,300 more than if they work through their own company. The Treasury Committee report also points out that the balance between tax and NICs has shifted over time: in 1980/81, the basic rate of tax was 30%, with employee class 1 NICs at 6.75% and employer NICs 10.2%. The equivalent rates today, 40 years later, are 20%, 12% and 13.8% – perhaps as a result of certain previous chancellors preferring to impose ‘stealth taxes’ by raising NIC rates rather than income tax rates.

The factors which I think are now combining to put pressure on this area are, firstly, that the problem is now being clearly recognised. The chancellor himself alluded to it when he introduced the SEISS and said that ‘it is now much harder to justify the inconsistent contributions between people of different employment statuses’ – and he has steadfastly refused to address the issue of those who have operated through owner-managed companies, many of whom have received little or no government support throughout the pandemic.

The second factor is the looming shift in responsibility for determining employment status, from the worker’s personal service company (PSC) to the engager, bringing the private sector in line with the public sector in this area from April 2021. This will finally put IR35 back where it was originally intended to be, with the onus on the buyer rather than the seller of services to ensure that tax is accounted for – but it is not going to be easy. Just last month, in the latest IR35 case, the Upper Tribunal decided that Kaye Adams, a journalist and broadcaster, did not fall within the intermediaries legislation (HMRC v Atholl House Productions Ltd [2021] UKUT 37 (TCC)). The problem is that there is no such thing as a ‘bright line’ test: the question of whether someone is employed or self-employed for tax purposes depends on all the facts and circumstances. And in employment law, there is the intermediate category of ‘worker’ which is highly relevant in the gig economy (see the Supreme Court’s decision in Uber BV and others v Aslam and others [2021] UKSC 5).

So, what should the chancellor do? First, he should set out his objectives – there is widespread agreement that the current system does not make sense; how far is he willing to go to change it? Second, he needs to set out the pathway to change – and that will not be easy. In particular, suddenly imposing higher NICs on the self-employed would be a heavy blow to the many small businesses that have suffered during covid – but reducing NICs on employees will not be easy either. The IFS paper, however, does set out some possible pathways to reform, where tax increases in one area could be balanced by more generous allowances elsewhere, making the overall package more palatable.

What we do not need (and here I disagree with the Treasury Committee) is a commission. The issues are well-known, and potential solutions have been put forward. We need a chancellor who is willing to take difficult decisions and carve a path to reform, rather than just putting increasingly expensive sticking plasters on the cracks in the system.

It remains to be seen whether Rishi Sunak will accept that challenge.

I make no apology for returning to the subject of tax after covid, after my early remarks in April 2020 and again in October. The Treasury Select Committee published its report on this topic on 1 March, and on 23 March we have the novel experience of ‘tax day’ when we are told we will see ‘a range of important but less high profile measures’.

It will be very disappointing if those consultations do not set out a roadmap for the direction of tax policy, over this life of this government and perhaps beyond. Business constantly says that what it needs is certainty in order to make investment decisions, and the Treasury Select Committee commented in its report that: ‘We believe that a tax strategy setting out what the government wants to achieve from the tax system and identifying high level objectives would have much merit.’ As someone who first proposed the idea of a roadmap to the Blair government in 1997, I would warmly welcome the government publishing, and regularly updating, its strategic objectives for the tax system.

A key area which is ripe for reform is the taxation of income from work. This is far from being a new topic, but a range of different factors may mean that now is the time to start on the path to fundamental change. As I said in my April 2020 article: ‘The need to design separate [covid support] schemes for the employed and self-employed, and the significant gap for owner-managed companies, highlights that business income in the UK is taxed very differently depending on precisely how it is received.’ The IFS has been saying this for some time, since the Mirrlees report of 2011 if not before, and in February 2021 Stuart Adam and Helen Miller published a detailed report titled Taxing work and investment across legal forms: pathways to well-designed taxes, which Judith Freedman referred to in her recent article in which she asked ‘does employment status matter for tax?’

The Treasury Committee report has an excellent chapter on this topic, which highlights that the underlying issue is not really taxation but national insurance contributions (NICs). As the chart below shows, the total tax and NICs burden for a job generating £40,000 is almost £12,000 for an employee, which is £3,300 more than for a self-employed individual and £4,300 more than if they work through their own company. The Treasury Committee report also points out that the balance between tax and NICs has shifted over time: in 1980/81, the basic rate of tax was 30%, with employee class 1 NICs at 6.75% and employer NICs 10.2%. The equivalent rates today, 40 years later, are 20%, 12% and 13.8% – perhaps as a result of certain previous chancellors preferring to impose ‘stealth taxes’ by raising NIC rates rather than income tax rates.

The factors which I think are now combining to put pressure on this area are, firstly, that the problem is now being clearly recognised. The chancellor himself alluded to it when he introduced the SEISS and said that ‘it is now much harder to justify the inconsistent contributions between people of different employment statuses’ – and he has steadfastly refused to address the issue of those who have operated through owner-managed companies, many of whom have received little or no government support throughout the pandemic.

The second factor is the looming shift in responsibility for determining employment status, from the worker’s personal service company (PSC) to the engager, bringing the private sector in line with the public sector in this area from April 2021. This will finally put IR35 back where it was originally intended to be, with the onus on the buyer rather than the seller of services to ensure that tax is accounted for – but it is not going to be easy. Just last month, in the latest IR35 case, the Upper Tribunal decided that Kaye Adams, a journalist and broadcaster, did not fall within the intermediaries legislation (HMRC v Atholl House Productions Ltd [2021] UKUT 37 (TCC)). The problem is that there is no such thing as a ‘bright line’ test: the question of whether someone is employed or self-employed for tax purposes depends on all the facts and circumstances. And in employment law, there is the intermediate category of ‘worker’ which is highly relevant in the gig economy (see the Supreme Court’s decision in Uber BV and others v Aslam and others [2021] UKSC 5).

So, what should the chancellor do? First, he should set out his objectives – there is widespread agreement that the current system does not make sense; how far is he willing to go to change it? Second, he needs to set out the pathway to change – and that will not be easy. In particular, suddenly imposing higher NICs on the self-employed would be a heavy blow to the many small businesses that have suffered during covid – but reducing NICs on employees will not be easy either. The IFS paper, however, does set out some possible pathways to reform, where tax increases in one area could be balanced by more generous allowances elsewhere, making the overall package more palatable.

What we do not need (and here I disagree with the Treasury Committee) is a commission. The issues are well-known, and potential solutions have been put forward. We need a chancellor who is willing to take difficult decisions and carve a path to reform, rather than just putting increasingly expensive sticking plasters on the cracks in the system.

It remains to be seen whether Rishi Sunak will accept that challenge.