Released by HM Treasury just before we all left for Christmas was a ten page document setting out the new world of tax policy. This considers the two changes announced at the 2016 Autumn Statement: namely, moving the Budget from the spring to the autumn; and the shift to a ‘single fiscal event’. In this article, Chris Sanger looks at the implications for those responding to consultations under the new framework and asks what’s new and what to look out for in the future.

As the evenings lengthened and with the first Autumn Budget delivered without a hitch, one might have expected HM Treasury to be ready to slow down before Christmas. But only five days after publishing one of the shorter Finance Bills (even if it was the third of the year!), those watching HM Treasury’s section of gov.uk would have seen a document appear, entitled The new Budget timetable and tax policy making process. Some ten pages in length, this web page might not have the catchiest of titles, or be presented like a consultation paper, but it nevertheless merits reading.

So what is this document? This is nothing short of the blueprint for how tax policy is going to be made in the future, following the twin changes announced in 2016 in the last ever Autumn Statement: namely, moving the Budget from the spring to the autumn; and the commitment to a ‘single fiscal event’. As well as covering the implications for timings of events, the document also provides an update on the tax policy making process, looking back at the past as well as providing glimpses into the future.

Whilst we have just had an Autumn Budget, we haven’t had a usual Budget timetable for some time, given two elections and the EU referendum in the last three years. So, in thinking of the future, it’s worth reflecting first on what the normal timetable used to be, as set out in the government’s 2010 document Tax policy making: a new approach.

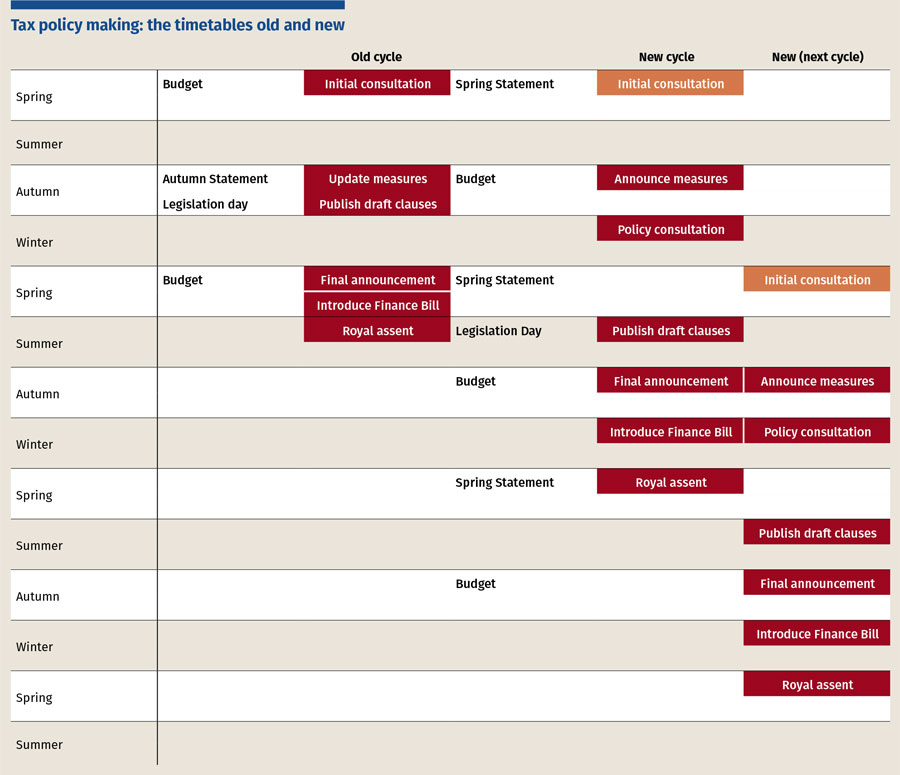

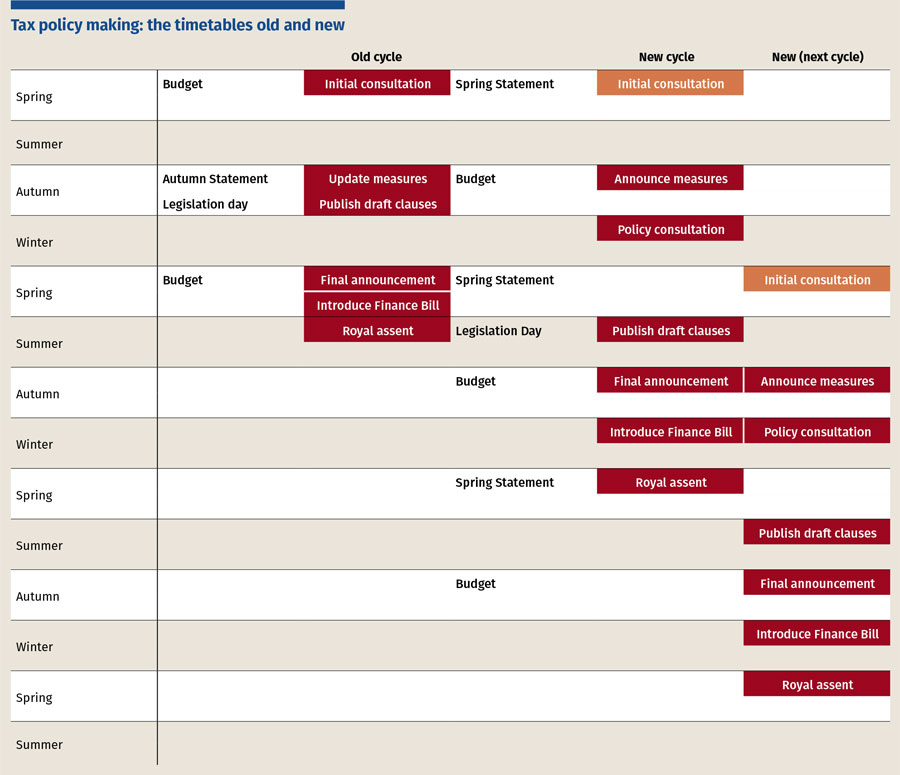

We used to have a March Budget that would set out some policy areas for consultation. These ideas would be captured in consultation documents that would be open until part way through the summer (or potentially through to September if released late). Having considered the responses, the government would then respond at the Autumn Statement and shortly thereafter, on ‘legislation day’ (or ‘L day’), with the ideas (suitably adapted) appearing as draft Finance Bill clauses. Those clauses would be open for consultation for at least eight weeks (covering Christmas!), giving a deadline of February. Then, the policies would be finalised at the Budget in the next month, with the Finance Bill being introduced to Parliament in April and receiving royal assent in July.

All in all, the process involved about a year of policy discussions followed by four months of Parliamentary scrutiny, meaning 16 months in total. Of course, we also saw policies announced at the Autumn Statement for delivery in the next Finance Bill, shortening the process by half. This can be seen in the first column in the diagram.

With the Budget moving to the autumn, the timetable changes, as set out in the two right hand columns of the diagram. The first thing to notice is the change in the timing of events:

The usual exception to this process remains, namely that the government will not consult on straightforward rates, allowances and threshold changes. The document also notes that other minor and technical changes may also not need or merit consultation. In these circumstances, the policies may be announced at the Budget to take effect four months later.

So what does this achieve? Well, it does deliver the Finance Act before the tax year to which the changes will apply. It also reduces the risk that the economic statement becomes a mini-Budget: in the old system, changes to personal allowances, etc. needed to be announced at the Autumn Statement to allow them to be included in software updates for the next tax year. With an Autumn Budget, there will be no such pressure on the Spring Statement.

Beyond this, the chancellor also committed to a ‘single fiscal event’, commenting that the statement would respond to the forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility, but would be ‘no major fiscal event’. This is reflected in the absence of announcements at the Spring Statement following the Budget.

The document reinforces this message, confirming that the ‘chancellor will not make significant tax or spending announcements at the Spring Statement’, with the usual caveat of ‘unless the economic circumstances require it’.

However, the Spring Statement is not wholly bereft of tax. Under the single fiscal event timetable, the normal gestation time for policy consultation to statute book would be 16 months. If a measure was likely to take longer, the government could announce something at the earlier Budget, thereby taking two cycles and extending the period to 28 months. That is a long time and therefore the document notes that it would be possible for the Spring Statement to start the consultation process:

‘the Spring Statement provides an opportunity to publish consultations, including early-stage consultation or call for evidence, before specific measures are announced (or the government decides not to proceed) at the following Budget.’

This flexibility (and indeed the acknowledgement that not all consultations will result in policy change) is welcome.

Armed with the new timetable, the rest of the document looks to update the government’s approach to tax policy making that was set out in the 2010 document Tax policy making: a new approach. As well as listing a number of the achievements in the areas of predictability, stability, simplicity and transparency, the document does recognise that ‘the approach taken has not always met the model and standard that was originally set out’.

This is evidenced by the reports of the Tax Professionals Forum (‘the Forum’), which was set up by the then financial secretary to the Treasury (FST) David Gauke, and now reports to the current FST Mel Stride. These reports (see bit.ly/19ZMYMt) have identified areas both where the process has been followed successfully and where there have been problems due to departures from the agreed approach.

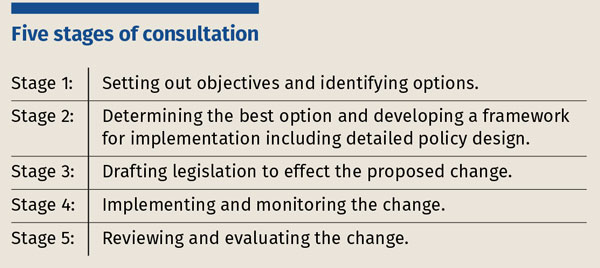

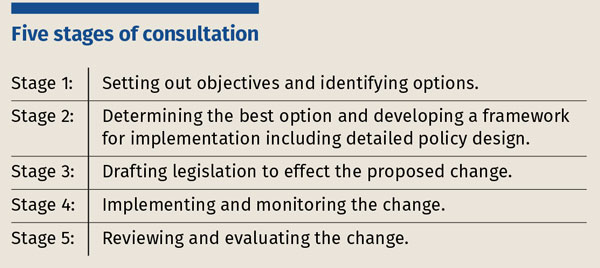

The document states that ‘the government recognises that there is scope to … improve on the record to date, particularly in relation to the consultation process’. It restates the commitment to the five stage consultation process (see box on previous page) and responds to the Forum’s repeated criticism that too many consultations are started at stage 3 (legislative design) rather than at the identification of options stage (stage 1). It notes that ‘the new tax policy making cycle provides an opportunity to consult more frequently from an earlier stage of policy development’. If delivered, this would indeed be a big step forward.

Another area where the government has responded to the Forum is the recognition that domestic tax policy is often influenced by consultation taking place at an international level. The document commits the government to aiming to align international and domestic policy consultation processes in a sensible way. Whilst the G20/OECD base erosion and profit shifting consultations are behind us, this recognition should hopefully mean that future global initiatives give rise to UK consultations.

Finally, in probably the biggest caveat, the document notes that leaving the European Union will inevitably involve changes to tax legislation and that these changes are ‘likely to merit exceptional treatment within the consultation timetable’.

So what does this all mean? Firstly, we have a new timetable to get used to, with consultations now coming out in March (at the Spring Statement before the Autumn Budget) and in December (following the Autumn Budget). We also have the prospect of two cycles overlapping, resulting in a plethora of consultations. To address this, the government is updating its consultation trackers and we should see this relaunching soon.

We also have draft legislation in July, and detailed Finance Bill scrutiny by Parliament over the winter months. Some of this may take some getting used to, but after the last year of two Budgets and the last few years of multiple Finance Bills, this timetable should be more manageable.

Secondly, we do have a recommitment to consultation and the tax policy making process and recognition that things need to improve. With a clear timetable for consultation, it will be interesting to see when the caveats are used to breach the standard approach. I wonder what the chancellor thinks is ‘an insignificant tax announcement’ that could be announced at the Spring Statement? I would imagine that the measure of significance would be in the ‘eye of the beholder’.

But this is a good step forward and the clarity provided by this document is helpful. It also commits the government to engaging with the Tax Professionals Forum to review and evaluate how the changes have performed against the aims set out in the document. That is something I look forward to, and I hope that we will be talking about how well the changes have worked. Here’s to a positive future!

Any views expressed are the author’s own and not necessarily those of the organisations he represents.

Released by HM Treasury just before we all left for Christmas was a ten page document setting out the new world of tax policy. This considers the two changes announced at the 2016 Autumn Statement: namely, moving the Budget from the spring to the autumn; and the shift to a ‘single fiscal event’. In this article, Chris Sanger looks at the implications for those responding to consultations under the new framework and asks what’s new and what to look out for in the future.

As the evenings lengthened and with the first Autumn Budget delivered without a hitch, one might have expected HM Treasury to be ready to slow down before Christmas. But only five days after publishing one of the shorter Finance Bills (even if it was the third of the year!), those watching HM Treasury’s section of gov.uk would have seen a document appear, entitled The new Budget timetable and tax policy making process. Some ten pages in length, this web page might not have the catchiest of titles, or be presented like a consultation paper, but it nevertheless merits reading.

So what is this document? This is nothing short of the blueprint for how tax policy is going to be made in the future, following the twin changes announced in 2016 in the last ever Autumn Statement: namely, moving the Budget from the spring to the autumn; and the commitment to a ‘single fiscal event’. As well as covering the implications for timings of events, the document also provides an update on the tax policy making process, looking back at the past as well as providing glimpses into the future.

Whilst we have just had an Autumn Budget, we haven’t had a usual Budget timetable for some time, given two elections and the EU referendum in the last three years. So, in thinking of the future, it’s worth reflecting first on what the normal timetable used to be, as set out in the government’s 2010 document Tax policy making: a new approach.

We used to have a March Budget that would set out some policy areas for consultation. These ideas would be captured in consultation documents that would be open until part way through the summer (or potentially through to September if released late). Having considered the responses, the government would then respond at the Autumn Statement and shortly thereafter, on ‘legislation day’ (or ‘L day’), with the ideas (suitably adapted) appearing as draft Finance Bill clauses. Those clauses would be open for consultation for at least eight weeks (covering Christmas!), giving a deadline of February. Then, the policies would be finalised at the Budget in the next month, with the Finance Bill being introduced to Parliament in April and receiving royal assent in July.

All in all, the process involved about a year of policy discussions followed by four months of Parliamentary scrutiny, meaning 16 months in total. Of course, we also saw policies announced at the Autumn Statement for delivery in the next Finance Bill, shortening the process by half. This can be seen in the first column in the diagram.

With the Budget moving to the autumn, the timetable changes, as set out in the two right hand columns of the diagram. The first thing to notice is the change in the timing of events:

The usual exception to this process remains, namely that the government will not consult on straightforward rates, allowances and threshold changes. The document also notes that other minor and technical changes may also not need or merit consultation. In these circumstances, the policies may be announced at the Budget to take effect four months later.

So what does this achieve? Well, it does deliver the Finance Act before the tax year to which the changes will apply. It also reduces the risk that the economic statement becomes a mini-Budget: in the old system, changes to personal allowances, etc. needed to be announced at the Autumn Statement to allow them to be included in software updates for the next tax year. With an Autumn Budget, there will be no such pressure on the Spring Statement.

Beyond this, the chancellor also committed to a ‘single fiscal event’, commenting that the statement would respond to the forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility, but would be ‘no major fiscal event’. This is reflected in the absence of announcements at the Spring Statement following the Budget.

The document reinforces this message, confirming that the ‘chancellor will not make significant tax or spending announcements at the Spring Statement’, with the usual caveat of ‘unless the economic circumstances require it’.

However, the Spring Statement is not wholly bereft of tax. Under the single fiscal event timetable, the normal gestation time for policy consultation to statute book would be 16 months. If a measure was likely to take longer, the government could announce something at the earlier Budget, thereby taking two cycles and extending the period to 28 months. That is a long time and therefore the document notes that it would be possible for the Spring Statement to start the consultation process:

‘the Spring Statement provides an opportunity to publish consultations, including early-stage consultation or call for evidence, before specific measures are announced (or the government decides not to proceed) at the following Budget.’

This flexibility (and indeed the acknowledgement that not all consultations will result in policy change) is welcome.

Armed with the new timetable, the rest of the document looks to update the government’s approach to tax policy making that was set out in the 2010 document Tax policy making: a new approach. As well as listing a number of the achievements in the areas of predictability, stability, simplicity and transparency, the document does recognise that ‘the approach taken has not always met the model and standard that was originally set out’.

This is evidenced by the reports of the Tax Professionals Forum (‘the Forum’), which was set up by the then financial secretary to the Treasury (FST) David Gauke, and now reports to the current FST Mel Stride. These reports (see bit.ly/19ZMYMt) have identified areas both where the process has been followed successfully and where there have been problems due to departures from the agreed approach.

The document states that ‘the government recognises that there is scope to … improve on the record to date, particularly in relation to the consultation process’. It restates the commitment to the five stage consultation process (see box on previous page) and responds to the Forum’s repeated criticism that too many consultations are started at stage 3 (legislative design) rather than at the identification of options stage (stage 1). It notes that ‘the new tax policy making cycle provides an opportunity to consult more frequently from an earlier stage of policy development’. If delivered, this would indeed be a big step forward.

Another area where the government has responded to the Forum is the recognition that domestic tax policy is often influenced by consultation taking place at an international level. The document commits the government to aiming to align international and domestic policy consultation processes in a sensible way. Whilst the G20/OECD base erosion and profit shifting consultations are behind us, this recognition should hopefully mean that future global initiatives give rise to UK consultations.

Finally, in probably the biggest caveat, the document notes that leaving the European Union will inevitably involve changes to tax legislation and that these changes are ‘likely to merit exceptional treatment within the consultation timetable’.

So what does this all mean? Firstly, we have a new timetable to get used to, with consultations now coming out in March (at the Spring Statement before the Autumn Budget) and in December (following the Autumn Budget). We also have the prospect of two cycles overlapping, resulting in a plethora of consultations. To address this, the government is updating its consultation trackers and we should see this relaunching soon.

We also have draft legislation in July, and detailed Finance Bill scrutiny by Parliament over the winter months. Some of this may take some getting used to, but after the last year of two Budgets and the last few years of multiple Finance Bills, this timetable should be more manageable.

Secondly, we do have a recommitment to consultation and the tax policy making process and recognition that things need to improve. With a clear timetable for consultation, it will be interesting to see when the caveats are used to breach the standard approach. I wonder what the chancellor thinks is ‘an insignificant tax announcement’ that could be announced at the Spring Statement? I would imagine that the measure of significance would be in the ‘eye of the beholder’.

But this is a good step forward and the clarity provided by this document is helpful. It also commits the government to engaging with the Tax Professionals Forum to review and evaluate how the changes have performed against the aims set out in the document. That is something I look forward to, and I hope that we will be talking about how well the changes have worked. Here’s to a positive future!

Any views expressed are the author’s own and not necessarily those of the organisations he represents.