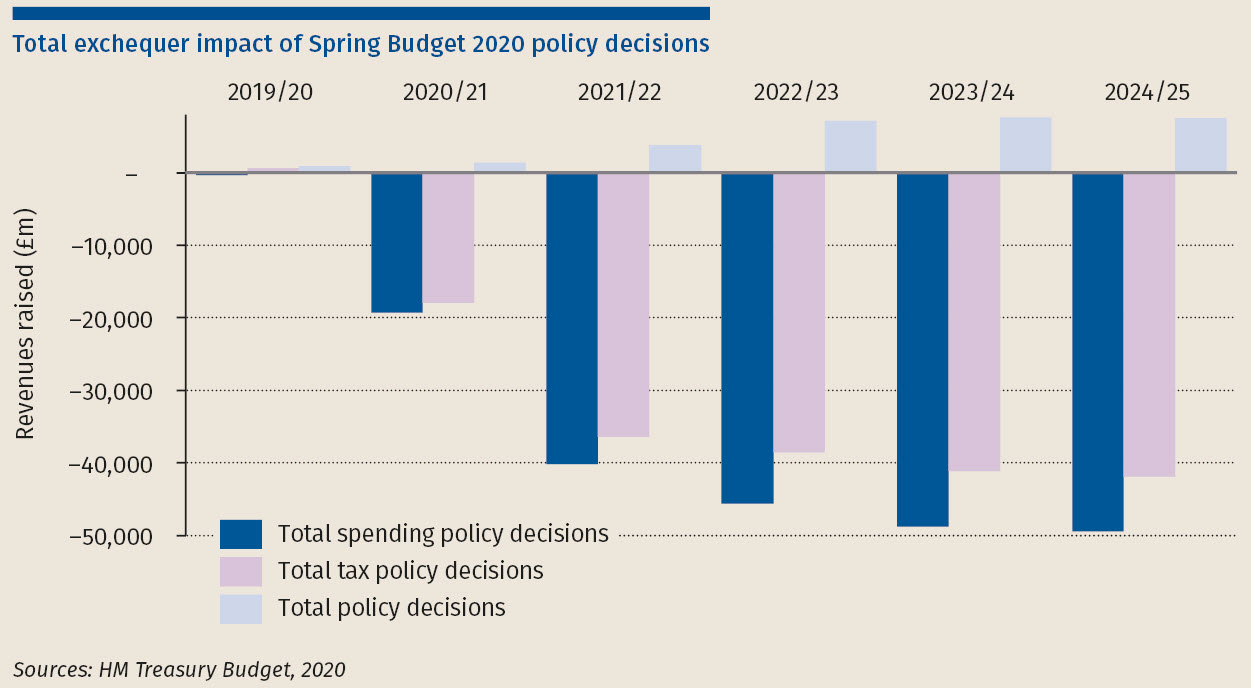

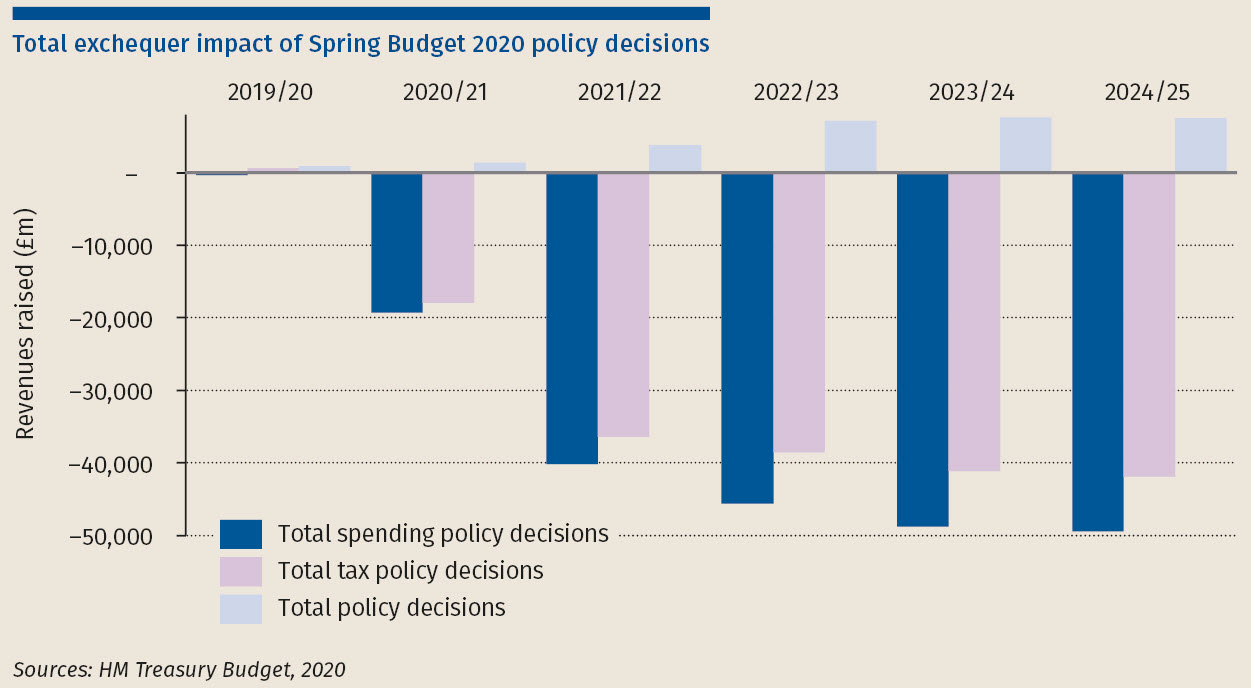

People like to put Budgets into nice, neat categories. Is it a spending or tax raising budget? Sometimes the answer is not entirely clear. But 11 March was not such a time. Based on the Red Book numbers, Budget 2020 was a spending budget to define all spending budgets, committing an additional £203bn to spending over six years while raising £28bn in taxes – an astounding difference of £175bn.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), whose job is to provide an independent assessment of the Budget, called it ‘the largest budget giveaway since 1992’. And that Budget was ahead of an election, credited with delivering John Major his unexpected electoral success. In contrast, this Budget is in the first year of a government with a strong majority, a situation that would traditionally result in tax rises – not tax cuts and spending increases.

But what about the COVID-19 stimulus – where do those numbers appear?

Well spotted! The above numbers do not include the emergency measures introduced in response to COVID-19. Indeed, the forecast of the economy by the OBR has been overtaken by events, not just by the spread of the coronavirus, but also by the oil price war, the share price fall and the cut in interest rates announced by the Bank of England earlier in the day. For this reason, the numbers in the chancellor’s speech were bigger even than those in his Red Book. Even without the COVID-19 spending, this Budget would have marked a huge boost to public spending. Taken together, the numbers in the chancellor’s speech are staggering.

What is being done on COVID-19?

On the day that the World Health Organisation declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, the chancellor set out the government’s economic response. The chancellor stressed that, in doing so, he was working closely with the independent Bank of England.

The government’s economic response to COVID-19 is threefold: support for the National Health Service, support for individuals, and support for business. The chancellor, whose speechwriter clearly has a fondness for triple alliteration, described the government’s actions as ‘coordinated, coherent and comprehensive’, as well as ‘temporary, timely and targeted’.

How much of the heavy lifting will tax do on COVID-19?

While a big proportion of the £30bn stimulus support package lies in spending measures, such as changes to rules on eligibility for statutory sick pay and contributory benefits, those looking for tax easements and help were not disappointed. As predicted, the chancellor accepted that the help needed was short term in nature and designed to support people and businesses through a challenging time ahead, before the economy would return to normal.

As a result, many of the changes are temporary in nature, running out in a year’s time. These included £1bn in one-year cuts in business rates for small retail, leisure and hospitality businesses (i.e. those with a rateable value of less than £51,000) and an increased business rates discount of £5,000 for pubs with a rateable value below £100,000. This means that in the next fiscal year, ‘nearly half of all business properties in England will not pay a penny of business rates’.

Support was also promised to struggling individuals and businesses through deferral of tax payments. HMRC has been instructed to scale up its Time to Pay service, with a dedicated helpline of 2,000 staff, and to waive late payment penalties and interest where a business has difficulty contacting HMRC or paying taxes due to COVID-19.

What happened to the manifesto commitments?

The chancellor may have reduced the number of jokes in the speech, but he kept returning to what is apparently to become his catch phrase – getting it done. In line with now familiar phrases of ‘Take back control’ and ‘Get Brexit done’, a three word summary of any policy seems now to be a necessity. As for the manifesto commitments, he did indeed ‘get it done’, with the scorecard including the increases in the research and development expenditure credit (from 12% to 13%), the structures and building allowance (from 2% to 3%) and the employment allowance (from £3,000 to £4,000).

The Budget also included the freeze in the corporation tax rate, which now needs to be followed by a Budget resolution by 31 March to avoid the two-percentage point cut in rate coming into effect on 1 April. This will have disappointed those who thought that such a rate cut could have been an effective stimulus measure.

Beyond business taxes, the Budget also delivered on the pledge to raise the national insurance threshold for employees, bringing it closer (but still significantly below) the income tax personal allowance. The aspiration remains to align the two levels at £12,500 but the chancellor wasn’t in the mood to move faster along this path.

We also saw the delivery of the SDLT surcharge on purchases by non-UK residents.

Any bread and butter tax business being done?

Some. Buried in the detail of the Red Book and accompanying documents was a change that many have been calling for – namely, the removal of the special rules for pre-FA 2002 intangible assets. Those with long memories will remember that Gordon Brown reformed the rules in that act to tax (and relieve) intangible assets on a revenue rather than capital basis. However, to avoid a sudden increase in costs, ‘old’ intellectual property was grandfathered under the old rules, creating a continuing need for two regimes.

This Budget changes this from 1 July, a rare example of simplification, with the chancellor spending about £100m per annum across the five-year forecast period. Changes like this bode well for those hoping that we will spend money on making the tax system simpler for all.

On another positive note, the chancellor raised the thresholds for pension tapering, increasing the two tapered annual allowance thresholds by £90,000. This is intended to address the concerns over doctors in the NHS being disincentivised to work, as it will take about 98% of consultants and 96% of GPs out of the taper altogether.

Where did the chancellor look for extra tax?

The chancellor responded to recent criticism of entrepreneurs’ relief (ER) by reducing its lifetime limit to £1m from £10m. I have argued that the criticism that ER rarely incentivises anyone to start up a business (as mentioned in the chancellor’s speech) misses the point of the relief, which is to encourage those who are successful to remain in the UK, pay tax, and go on to create more growth, jobs and success in the future. The change applies to disposals on or after Budget day and such immediate action will stop forestalling, particularly when combined with additional anti-avoidance announced alongside. Those successful entrepreneurs with gains above the new limit who thought that they had until the end of the tax year to act will be sorely disappointed.

One area where there was speculation that the chancellor might take a different stance than his predecessor was in relation to digital services tax (DST), particularly given the intense debate between the US and France. Following the threat of tariffs, the French government agreed to defer collection DST on this year’s revenue until 2021.

In the event, the Budget merely confirmed the announcement in July last year that the tax would be collected on an annual basis, thereby meaning that, although the tax starts from 1 April this year, no UK DST would be collected before 2021. More widely, the costings were updated slightly, now showing total tax receipts from DST in 2023/24 of £460m. The chancellor must be thinking that it’s worth risking a heated discussion with the US for a prize like that. It also appears that the OBR was not convinced that by then the OECD would deliver on BEPS 2.0 or, as the Treasury describes it, ‘a multilateral solution to the challenges digitalisation has created for the corporate tax system’. If it had been convinced, it would not have booked the revenue as the UK has committed to remove the tax if that does happen.

Other taxes that were pre-planned were the off-payroll workers rules (IR35) and the plastic packaging tax. The former proceeded as planned, while small changes were announced to the latter, such as removing the incentive to package goods outside the UK and import the filled plastic packaging.

The environmental credentials of this tax rely on the fact that increasing the use of recycled plastic will reduce overall plastic waste. In many situations this may be the case, but there are clear examples where the move to incorporating recycled plastic could well increase plastic waste. Those reading through the accompanying consultation document will hope that the Treasury remains open to addressing these issues, as well as the more technical elements of tax design.

Any crowd pleasers?

Strangely for a Budget with such a huge bias towards spending, the chancellor also opted to use his limited range of tax levers (having committed not to raise the headline rates of income tax, NICs and VAT) to distribute further largesse, rather than claw back some revenue. This saw:

Conclusion

Going into this Budget, expectations had been of few actions and lots of consultations. In the event it was the reverse, with 76 measures and only a few consultations.

So, what more should we expect? Well, in addition to the Finance Bill next week, we also have a few consultations to respond to or wait for. A key one for many will be on the future of business rates. In the event, the Budget merely set out the objectives (reducing the burden, improving the system and considering fundamental change) and scope, promising a call for evidence in spring 2020 and a report in the autumn.

All in all, this is a Budget in which ‘things got done’. But, as the chancellor, less than one month into his job, may now be finding, even with all that, there’s a long list of other items still to be tackled. He may be pleased that, despite the best laid plans to have only one fiscal event per year, the chancellor has another opportunity in the autumn. It’s going to be a busy year – we’re going to need to get lots more done.

People like to put Budgets into nice, neat categories. Is it a spending or tax raising budget? Sometimes the answer is not entirely clear. But 11 March was not such a time. Based on the Red Book numbers, Budget 2020 was a spending budget to define all spending budgets, committing an additional £203bn to spending over six years while raising £28bn in taxes – an astounding difference of £175bn.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), whose job is to provide an independent assessment of the Budget, called it ‘the largest budget giveaway since 1992’. And that Budget was ahead of an election, credited with delivering John Major his unexpected electoral success. In contrast, this Budget is in the first year of a government with a strong majority, a situation that would traditionally result in tax rises – not tax cuts and spending increases.

But what about the COVID-19 stimulus – where do those numbers appear?

Well spotted! The above numbers do not include the emergency measures introduced in response to COVID-19. Indeed, the forecast of the economy by the OBR has been overtaken by events, not just by the spread of the coronavirus, but also by the oil price war, the share price fall and the cut in interest rates announced by the Bank of England earlier in the day. For this reason, the numbers in the chancellor’s speech were bigger even than those in his Red Book. Even without the COVID-19 spending, this Budget would have marked a huge boost to public spending. Taken together, the numbers in the chancellor’s speech are staggering.

What is being done on COVID-19?

On the day that the World Health Organisation declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, the chancellor set out the government’s economic response. The chancellor stressed that, in doing so, he was working closely with the independent Bank of England.

The government’s economic response to COVID-19 is threefold: support for the National Health Service, support for individuals, and support for business. The chancellor, whose speechwriter clearly has a fondness for triple alliteration, described the government’s actions as ‘coordinated, coherent and comprehensive’, as well as ‘temporary, timely and targeted’.

How much of the heavy lifting will tax do on COVID-19?

While a big proportion of the £30bn stimulus support package lies in spending measures, such as changes to rules on eligibility for statutory sick pay and contributory benefits, those looking for tax easements and help were not disappointed. As predicted, the chancellor accepted that the help needed was short term in nature and designed to support people and businesses through a challenging time ahead, before the economy would return to normal.

As a result, many of the changes are temporary in nature, running out in a year’s time. These included £1bn in one-year cuts in business rates for small retail, leisure and hospitality businesses (i.e. those with a rateable value of less than £51,000) and an increased business rates discount of £5,000 for pubs with a rateable value below £100,000. This means that in the next fiscal year, ‘nearly half of all business properties in England will not pay a penny of business rates’.

Support was also promised to struggling individuals and businesses through deferral of tax payments. HMRC has been instructed to scale up its Time to Pay service, with a dedicated helpline of 2,000 staff, and to waive late payment penalties and interest where a business has difficulty contacting HMRC or paying taxes due to COVID-19.

What happened to the manifesto commitments?

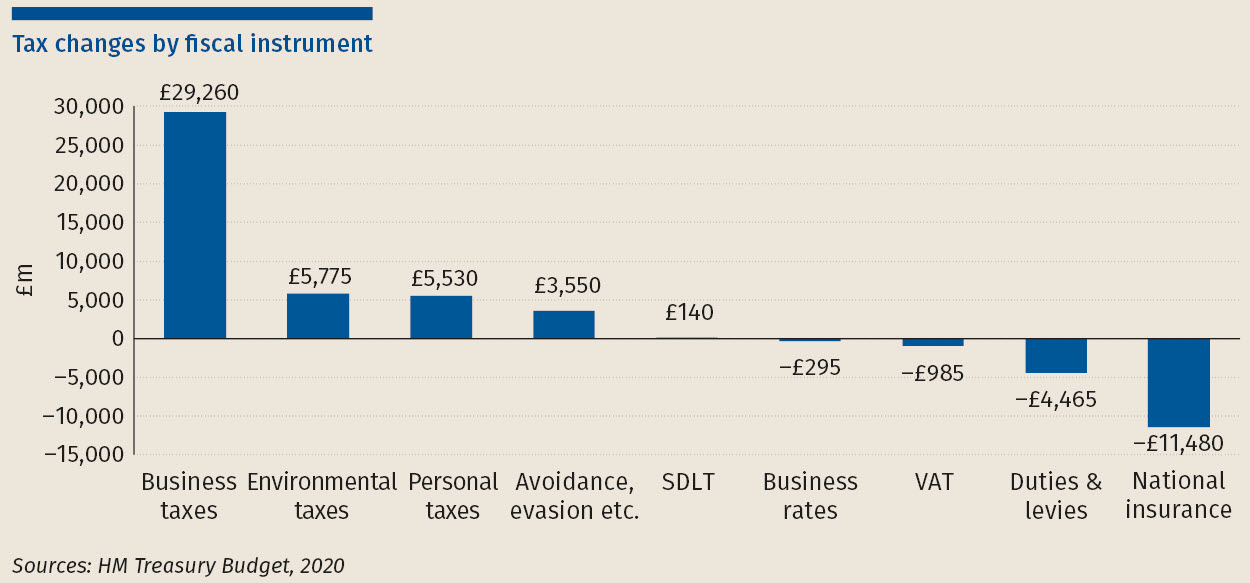

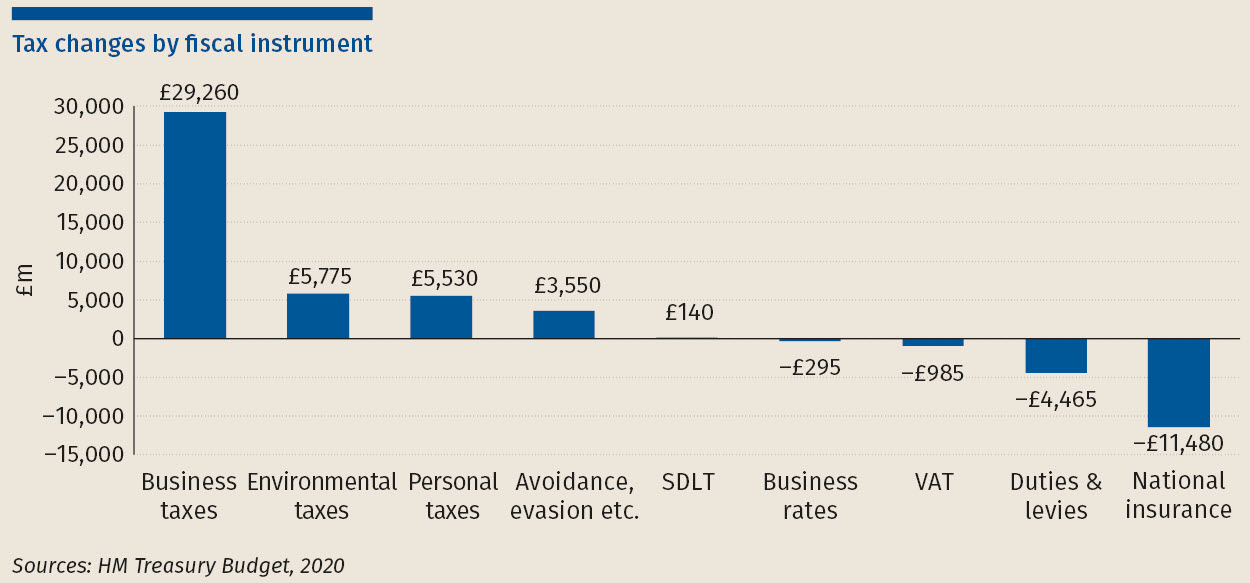

The chancellor may have reduced the number of jokes in the speech, but he kept returning to what is apparently to become his catch phrase – getting it done. In line with now familiar phrases of ‘Take back control’ and ‘Get Brexit done’, a three word summary of any policy seems now to be a necessity. As for the manifesto commitments, he did indeed ‘get it done’, with the scorecard including the increases in the research and development expenditure credit (from 12% to 13%), the structures and building allowance (from 2% to 3%) and the employment allowance (from £3,000 to £4,000).

The Budget also included the freeze in the corporation tax rate, which now needs to be followed by a Budget resolution by 31 March to avoid the two-percentage point cut in rate coming into effect on 1 April. This will have disappointed those who thought that such a rate cut could have been an effective stimulus measure.

Beyond business taxes, the Budget also delivered on the pledge to raise the national insurance threshold for employees, bringing it closer (but still significantly below) the income tax personal allowance. The aspiration remains to align the two levels at £12,500 but the chancellor wasn’t in the mood to move faster along this path.

We also saw the delivery of the SDLT surcharge on purchases by non-UK residents.

Any bread and butter tax business being done?

Some. Buried in the detail of the Red Book and accompanying documents was a change that many have been calling for – namely, the removal of the special rules for pre-FA 2002 intangible assets. Those with long memories will remember that Gordon Brown reformed the rules in that act to tax (and relieve) intangible assets on a revenue rather than capital basis. However, to avoid a sudden increase in costs, ‘old’ intellectual property was grandfathered under the old rules, creating a continuing need for two regimes.

This Budget changes this from 1 July, a rare example of simplification, with the chancellor spending about £100m per annum across the five-year forecast period. Changes like this bode well for those hoping that we will spend money on making the tax system simpler for all.

On another positive note, the chancellor raised the thresholds for pension tapering, increasing the two tapered annual allowance thresholds by £90,000. This is intended to address the concerns over doctors in the NHS being disincentivised to work, as it will take about 98% of consultants and 96% of GPs out of the taper altogether.

Where did the chancellor look for extra tax?

The chancellor responded to recent criticism of entrepreneurs’ relief (ER) by reducing its lifetime limit to £1m from £10m. I have argued that the criticism that ER rarely incentivises anyone to start up a business (as mentioned in the chancellor’s speech) misses the point of the relief, which is to encourage those who are successful to remain in the UK, pay tax, and go on to create more growth, jobs and success in the future. The change applies to disposals on or after Budget day and such immediate action will stop forestalling, particularly when combined with additional anti-avoidance announced alongside. Those successful entrepreneurs with gains above the new limit who thought that they had until the end of the tax year to act will be sorely disappointed.

One area where there was speculation that the chancellor might take a different stance than his predecessor was in relation to digital services tax (DST), particularly given the intense debate between the US and France. Following the threat of tariffs, the French government agreed to defer collection DST on this year’s revenue until 2021.

In the event, the Budget merely confirmed the announcement in July last year that the tax would be collected on an annual basis, thereby meaning that, although the tax starts from 1 April this year, no UK DST would be collected before 2021. More widely, the costings were updated slightly, now showing total tax receipts from DST in 2023/24 of £460m. The chancellor must be thinking that it’s worth risking a heated discussion with the US for a prize like that. It also appears that the OBR was not convinced that by then the OECD would deliver on BEPS 2.0 or, as the Treasury describes it, ‘a multilateral solution to the challenges digitalisation has created for the corporate tax system’. If it had been convinced, it would not have booked the revenue as the UK has committed to remove the tax if that does happen.

Other taxes that were pre-planned were the off-payroll workers rules (IR35) and the plastic packaging tax. The former proceeded as planned, while small changes were announced to the latter, such as removing the incentive to package goods outside the UK and import the filled plastic packaging.

The environmental credentials of this tax rely on the fact that increasing the use of recycled plastic will reduce overall plastic waste. In many situations this may be the case, but there are clear examples where the move to incorporating recycled plastic could well increase plastic waste. Those reading through the accompanying consultation document will hope that the Treasury remains open to addressing these issues, as well as the more technical elements of tax design.

Any crowd pleasers?

Strangely for a Budget with such a huge bias towards spending, the chancellor also opted to use his limited range of tax levers (having committed not to raise the headline rates of income tax, NICs and VAT) to distribute further largesse, rather than claw back some revenue. This saw:

Conclusion

Going into this Budget, expectations had been of few actions and lots of consultations. In the event it was the reverse, with 76 measures and only a few consultations.

So, what more should we expect? Well, in addition to the Finance Bill next week, we also have a few consultations to respond to or wait for. A key one for many will be on the future of business rates. In the event, the Budget merely set out the objectives (reducing the burden, improving the system and considering fundamental change) and scope, promising a call for evidence in spring 2020 and a report in the autumn.

All in all, this is a Budget in which ‘things got done’. But, as the chancellor, less than one month into his job, may now be finding, even with all that, there’s a long list of other items still to be tackled. He may be pleased that, despite the best laid plans to have only one fiscal event per year, the chancellor has another opportunity in the autumn. It’s going to be a busy year – we’re going to need to get lots more done.