The stability of the Scottish Budget appearing in its ‘normal’ timeslot was balanced by some fairly radical departures from UK tax policy, write Isobel d’Inverno and Alan Barr (Brodies).

In its Programme for government 2021/22, the Scottish government had promised stability in relation to rates of both income tax and land and buildings transaction tax. This was repeated in the Scottish Budget delivered in December 2021. Things change, to put it mildly. The promise was not repeated in the Programme for government 2022/23. By the time the Scottish Budget was delivered on 15 December 2022, the UK had been through the tax rollercoaster of three Budgets in 2022, none of which was actually called a Budget (a Spring Statement, a Growth Plan and an Autumn Statement). The external factors affecting UK economic policy – the aftermaths of Covid and Brexit, rampant inflation at least partially driven by relatively nearby war – were at least as relevant in Scotland as in the rest of the UK and undoubtedly drove what was proposed for Scottish taxpayers.

Proposals for substantial changes for those taxes still fully or partially in the control of Westminster had come, and in some cases gone, by the time the Scottish government presented its proposals for 2023/24. But putting aside the turmoil affecting UK tax policy earlier in the year, the Scottish Budget could be given with reasonable certainty that the proposals in the last of the UK fiscal events, the Autumn Statement, would actually be enacted to take effect in 2023/24. In that sense only, there was a return to the desired time pattern for Scottish Budgets, which is that they should follow by at least six weeks UK announcements on tax (but should be able to be made in good time for the start of the new tax year).

While timing in the macro sense was back to normal, the actual delivery of the Budget was delayed from its appointed hour by another phenomenon that has become endemic in tax policy: actual or alleged leaks of that policy before its presentation to Parliament. There were a number of accurate (as it turned out) predictions of what would be said. The presiding officer wished to investigate but after those investigations, she allowed John Swinney (standing in for Kate Forbes, the cabinet secretary for Finance and the Economy, on maternity leave) to proceed.

What followed was a Budget which was said to raise about £1bn more than would have been the case than if rUK decisions had been replicated. This was in keeping with principles set out in a publication by the Scottish government from 2021, the Framework for tax. In that document, an allegedly distinctive Scottish approach to taxation was set out in a number of principles. To the extent that these principles were put into practice in the 2022/23 Budget, this involved increased divergence between income tax rates for Scottish taxpayers on earned and property income as compared to the rest of the UK. Those earning above average are set to pay somewhat more (and those earning considerably above average will see it as considerably more) and lower earners a small amount less, in each case as compared to their equivalents (if such can be identified) in the rest of the UK.

A considerable tweak was made to one aspect of land and buildings transaction tax (Scotland’s property stamp duty, the most fully devolved and divergent tax from its rUK equivalents), with changes in, and developments in relation to, other devolved taxes being much more limited.

It is of course possible that further external events, including for this purpose the (next and ‘real’) UK Budget now announced for 15 March 2023 could deflect some of the Scottish government’s proposals and demand ‘in-year’ adjustments. But with that caveat, it seems likely that the announcements made in the Scottish Budget on 15 December 2022 will come into effect.

Income tax is only partially devolved: the Scottish Parliament can set rates and thresholds as they affect only earned and property income; other rules, structures and reliefs (including the level of personal allowance), as well as the rates affecting dividend and other investment income, remain controlled by Westminster. The same applies to national insurance contributions, which have of course been through their own rollercoaster of proposed and withdrawn changes in 2022 in the UK Parliament.

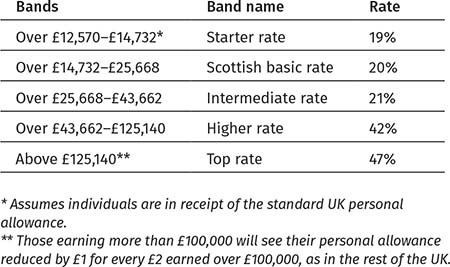

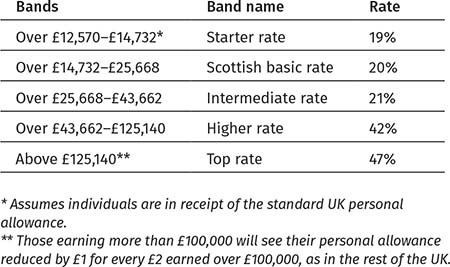

With regard to income tax, the first announcement made derived directly from its UK equivalent: the lowering of the threshold for the highest rate of tax (in Scotland termed the ‘top rate’) from £150,000 to £125,140. Other thresholds are to remain unchanged. But there was then an announcement that the top rate itself and the rate below that, the Scottish higher rate, would each be increased by 1%, to 47% and 42% respectively, with other rates maintained. Without actual hypothecation, the 1% increase was stated to be intended for use to increase further the NHS spending increase which would reach Scotland by means of the Barnett formula. The announcement on rates and thresholds, coupled with the five-rate structure already in place for taxable income above the personal allowance, produces the following table of tax rates on earned and property income for Scottish taxpayers for 2023/24:

As is the case throughout the UK, but with a particular emphasis applicable in Scotland, this structure produces some anomalous (for which read ‘very high’) marginal rates. In particular, NIC thresholds and the reduction in the main rates of NICs which takes place when income exceeds certain levels are now tied to the rUK higher rate income tax threshold (confirmed in the Autumn Statement, purportedly for the next several years until April 2028, at £50,270). This means that an employee with earnings between the Scottish higher rate threshold of £43,662 and the rUK higher rate threshold of £50,270 will suffer a marginal income tax and NI rate of 54% on that ‘slice’ of income – and a combination of fiscal drag and high inflation are pulling ever more taxpayers into that bracket. Unlike the UK Autumn Statement, the Scottish Budget contained no announcement about freezing thresholds for future years, but increases at the rate of inflation seem unlikely.

A second marginal anomaly, but one better known throughout the UK (although of slightly lesser effect in rUK than in Scotland) occurs when income rises above £100,000 and the withdrawal of the personal allowance is implemented. For Scottish taxpayers with earned/property income above that level, the slice of income between £100,000 and £125,140 will now be subject to income tax at an eye-watering marginal rate of 63% – with 2% NICs payable in addition.

Whether such anomalies – and perhaps more pertinently the differential of 2% now to be applicable between the rUK additional rate of 45% and the Scottish top rate of 47% – will drive more Scottish taxpayers to attempt to lose their status as such remains to be seen. For those wishing to do so, it must be remembered that the status of ‘Scottish taxpayer’ derives from factors much more commonly found in considerations of domicile than those encountered when considering a taxpayer’s residence. The course may be available to some Scottish taxpayers, but it is far from an open road. In the meantime, those earning more than £43,662 as Scottish taxpayers for employers who have comparable English-based employees will see somewhat increased differences in what they take home. Whether that is balanced or indeed outweighed by differential Scottish government spending decisions will depend very much on personal and family circumstances.

A very unexpected development was the increase in the rate of the additional dwelling supplement (ADS) from 4% to 6% with effect from 16 December 2022. This means that the rate of ADS has doubled since it was introduced in 2016.

The ADS is the additional LBTT charge which applies to purchases of second homes and buy-to-let properties, as well as to a range of other transactions where the purchaser or connected parties already own a dwelling. ADS also applies to any purchase of a dwelling by a company, and to many purchases by trusts and partnerships. The ADS operates in a similar way to the SDLT higher rates for additional dwellings (HRAD), but with some notable exceptions, for example the ADS is payable on mixed purchases (on the price apportioned to dwellings) and there is no equivalent in ADS for the relief from HRAD for ‘subsidiary dwellings’ (the granny flat exception). There is also, however, no equivalent in LBTT to the SDLT 2% surcharge for the purchase of residential property by non-residents.

The change was made by statutory instrument – The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Additional Amount: Transactions Relating to Second Homes etc.) (Scotland) Amendment Order, SSI 2022/375 – which was laid before the Scottish Parliament on Budget Day (15 December 2022) and came into force on 16 December 2022.

There is a limited transitional relief, in that the new 6% rate does not apply to transactions where a contract was entered into prior to 16 December 2022. As is usual for the transitional rules for LBTT and ADS rate changes, it does not matter if a pre-16 December contract is conditional, or if it is varied or assigned.

The impact of the ADS increase will be significant for many purchasers. The residential rates of LBTT are higher than those which apply in other parts of the UK, and the increase in ADS creates a further divergence. The total tax (LBTT and ADS) on a £250,000 second home in Scotland is now £17,100, compared to £7,500 on an equivalent property in England or Northern Ireland, and £12,450 for an equivalent property in Wales. For a £1,000,000 second home, the total tax in Scotland is now £138,350 compared to £71,250 in England or Northern Ireland and £101,200 in Wales.

In December 2021, the Scottish government launched a review of the ADS (The land and buildings transaction tax – additional dwelling supplement: a call for evidence and views). The main areas addressed in the consultation were:

The consultation closed on 11 March 2022, but the results have yet to be published. The Scottish government confirmed in the Budget that a response to the ADS consultation will be published early in 2023, together with a consultation on draft legislation.

Scottish landfill tax (SLfT) is a fully devolved Scottish tax which applies to the disposal of waste to landfill in Scotland. The standard rate of SLfT will increase to £102.10 per tonne and the lower rate of SLfT to £3.25 per tonne with effect from 1 April 2023, in line with UK landfill tax increases. Maintaining consistency with the UK rates is intended to avoid ‘waste tourism’, i.e. the moving of waste around the UK to take advantage of a lower tax charge on landfill in one part of the UK.

The Scotland Act 2016 provided for the devolution of aggregates levy to Scotland, but the process was delayed by longstanding litigation relating to the UK aggregates levy and by a review of the UK levy in 2020. The Scottish government is now working towards the introduction of a Scottish Aggregates Levy Bill and a consultation on the design of the new tax was held in 2022 entitled Breaking new ground? Developing a Scottish tax to replace the UK aggregates levy: consultation.

A key focus of the new tax is to support the circular economy, including recycling of aggregate, but devolution of the aggregates levy could involve particular issues for companies which operate on a UK wide basis. These include potential double taxation and other issues relating to the interaction between the UK and Scottish taxes. Although the Scottish government is keen to introduce a distinctive new tax, there could also be tensions if the rates of aggregates levy differ across the UK, or if the Scottish reliefs operate differently from those in the rest of the UK. The Scottish aggregates levy will be administered and collected by Revenue Scotland, and it will be important to ensure that sufficient sanctions are included in the new tax to ensure compliance. The provisional date for introducing the Scottish aggregates levy is 1 April 2025, and the UK aggregates levy will apply until that time.

Air departure tax (ADT) is the planned replacement for air passenger duty (APD) for passengers departing from Scottish airports. Legislation for the ADT has been passed (The Air Departure Tax (Scotland) Act 2017) but implementation has been delayed. A number of issues are still to be resolved, including how to retain in ADT the current exemption from APD which applies to flights departing from airports in the Highlands and Islands. The Scottish government is also considering the rates of ADT against its climate change objectives. The Scottish government remains committed to the introduction of ADT once solutions to these issues can be found.

The Scotland Act 2016 allows for half of VAT receipts attributable to Scotland (10p of the standard rate of VAT and 2.5p of the reduced rate) to be assigned to the Scottish government. VAT rates will continue to be set at a UK wide level. Arriving at the VAT attributable to Scotland to form the basis for assignment has proved to be extremely challenging: the figures cannot be extracted from VAT returns, and requiring separate ‘Scottish’ VAT returns to be submitted would be both unworkable and unwelcome. A model based on expenditure in Scotland has been jointly developed by the Scottish and UK governments, and is being used by the Scottish Fiscal Commission to forecast assigned VAT revenues.

VAT assignment was due to be introduced from April 2021, but due to the uncertainty caused by Covid-19 and EU exit, the UK and Scottish governments agreed to postpone implementation. The plans for VAT assignment are being considered as part of the current review of the Fiscal Framework. This is the agreement between the UK and Scottish governments which sets out how Scotland’s tax and social security powers are managed and implemented, and how funding for the Scottish Budget is adjusted following devolution of taxes and social security (the block grant adjustments).

The stability of the Scottish Budget appearing in its ‘normal’ timeslot was balanced by some fairly radical departures from UK tax policy. Until the leaks on Budget day itself, few would have predicted the 1p rise in the top two rates of Scottish income tax, although the replication (at least) of the reduction in the top rate threshold was a near-certainty. The 50% rise in the ADS rate was also a surprise; it will be interesting to see if this is a tax too far for at least some elements of the Scottish housing market. Those particular changes are perfect illustrations of the continuing opportunities and limitations on a partially devolved tax system – one going a little further in the direction of travel taken at Westminster where there is little scope for a completely different road; the other increasing very obviously the differences between the completely devolved LBTT and its SDLT forebear. The expectation must be that the tax roads will continue to diverge, as one approaches Berwick-on-Tweed.

The stability of the Scottish Budget appearing in its ‘normal’ timeslot was balanced by some fairly radical departures from UK tax policy, write Isobel d’Inverno and Alan Barr (Brodies).

In its Programme for government 2021/22, the Scottish government had promised stability in relation to rates of both income tax and land and buildings transaction tax. This was repeated in the Scottish Budget delivered in December 2021. Things change, to put it mildly. The promise was not repeated in the Programme for government 2022/23. By the time the Scottish Budget was delivered on 15 December 2022, the UK had been through the tax rollercoaster of three Budgets in 2022, none of which was actually called a Budget (a Spring Statement, a Growth Plan and an Autumn Statement). The external factors affecting UK economic policy – the aftermaths of Covid and Brexit, rampant inflation at least partially driven by relatively nearby war – were at least as relevant in Scotland as in the rest of the UK and undoubtedly drove what was proposed for Scottish taxpayers.

Proposals for substantial changes for those taxes still fully or partially in the control of Westminster had come, and in some cases gone, by the time the Scottish government presented its proposals for 2023/24. But putting aside the turmoil affecting UK tax policy earlier in the year, the Scottish Budget could be given with reasonable certainty that the proposals in the last of the UK fiscal events, the Autumn Statement, would actually be enacted to take effect in 2023/24. In that sense only, there was a return to the desired time pattern for Scottish Budgets, which is that they should follow by at least six weeks UK announcements on tax (but should be able to be made in good time for the start of the new tax year).

While timing in the macro sense was back to normal, the actual delivery of the Budget was delayed from its appointed hour by another phenomenon that has become endemic in tax policy: actual or alleged leaks of that policy before its presentation to Parliament. There were a number of accurate (as it turned out) predictions of what would be said. The presiding officer wished to investigate but after those investigations, she allowed John Swinney (standing in for Kate Forbes, the cabinet secretary for Finance and the Economy, on maternity leave) to proceed.

What followed was a Budget which was said to raise about £1bn more than would have been the case than if rUK decisions had been replicated. This was in keeping with principles set out in a publication by the Scottish government from 2021, the Framework for tax. In that document, an allegedly distinctive Scottish approach to taxation was set out in a number of principles. To the extent that these principles were put into practice in the 2022/23 Budget, this involved increased divergence between income tax rates for Scottish taxpayers on earned and property income as compared to the rest of the UK. Those earning above average are set to pay somewhat more (and those earning considerably above average will see it as considerably more) and lower earners a small amount less, in each case as compared to their equivalents (if such can be identified) in the rest of the UK.

A considerable tweak was made to one aspect of land and buildings transaction tax (Scotland’s property stamp duty, the most fully devolved and divergent tax from its rUK equivalents), with changes in, and developments in relation to, other devolved taxes being much more limited.

It is of course possible that further external events, including for this purpose the (next and ‘real’) UK Budget now announced for 15 March 2023 could deflect some of the Scottish government’s proposals and demand ‘in-year’ adjustments. But with that caveat, it seems likely that the announcements made in the Scottish Budget on 15 December 2022 will come into effect.

Income tax is only partially devolved: the Scottish Parliament can set rates and thresholds as they affect only earned and property income; other rules, structures and reliefs (including the level of personal allowance), as well as the rates affecting dividend and other investment income, remain controlled by Westminster. The same applies to national insurance contributions, which have of course been through their own rollercoaster of proposed and withdrawn changes in 2022 in the UK Parliament.

With regard to income tax, the first announcement made derived directly from its UK equivalent: the lowering of the threshold for the highest rate of tax (in Scotland termed the ‘top rate’) from £150,000 to £125,140. Other thresholds are to remain unchanged. But there was then an announcement that the top rate itself and the rate below that, the Scottish higher rate, would each be increased by 1%, to 47% and 42% respectively, with other rates maintained. Without actual hypothecation, the 1% increase was stated to be intended for use to increase further the NHS spending increase which would reach Scotland by means of the Barnett formula. The announcement on rates and thresholds, coupled with the five-rate structure already in place for taxable income above the personal allowance, produces the following table of tax rates on earned and property income for Scottish taxpayers for 2023/24:

As is the case throughout the UK, but with a particular emphasis applicable in Scotland, this structure produces some anomalous (for which read ‘very high’) marginal rates. In particular, NIC thresholds and the reduction in the main rates of NICs which takes place when income exceeds certain levels are now tied to the rUK higher rate income tax threshold (confirmed in the Autumn Statement, purportedly for the next several years until April 2028, at £50,270). This means that an employee with earnings between the Scottish higher rate threshold of £43,662 and the rUK higher rate threshold of £50,270 will suffer a marginal income tax and NI rate of 54% on that ‘slice’ of income – and a combination of fiscal drag and high inflation are pulling ever more taxpayers into that bracket. Unlike the UK Autumn Statement, the Scottish Budget contained no announcement about freezing thresholds for future years, but increases at the rate of inflation seem unlikely.

A second marginal anomaly, but one better known throughout the UK (although of slightly lesser effect in rUK than in Scotland) occurs when income rises above £100,000 and the withdrawal of the personal allowance is implemented. For Scottish taxpayers with earned/property income above that level, the slice of income between £100,000 and £125,140 will now be subject to income tax at an eye-watering marginal rate of 63% – with 2% NICs payable in addition.

Whether such anomalies – and perhaps more pertinently the differential of 2% now to be applicable between the rUK additional rate of 45% and the Scottish top rate of 47% – will drive more Scottish taxpayers to attempt to lose their status as such remains to be seen. For those wishing to do so, it must be remembered that the status of ‘Scottish taxpayer’ derives from factors much more commonly found in considerations of domicile than those encountered when considering a taxpayer’s residence. The course may be available to some Scottish taxpayers, but it is far from an open road. In the meantime, those earning more than £43,662 as Scottish taxpayers for employers who have comparable English-based employees will see somewhat increased differences in what they take home. Whether that is balanced or indeed outweighed by differential Scottish government spending decisions will depend very much on personal and family circumstances.

A very unexpected development was the increase in the rate of the additional dwelling supplement (ADS) from 4% to 6% with effect from 16 December 2022. This means that the rate of ADS has doubled since it was introduced in 2016.

The ADS is the additional LBTT charge which applies to purchases of second homes and buy-to-let properties, as well as to a range of other transactions where the purchaser or connected parties already own a dwelling. ADS also applies to any purchase of a dwelling by a company, and to many purchases by trusts and partnerships. The ADS operates in a similar way to the SDLT higher rates for additional dwellings (HRAD), but with some notable exceptions, for example the ADS is payable on mixed purchases (on the price apportioned to dwellings) and there is no equivalent in ADS for the relief from HRAD for ‘subsidiary dwellings’ (the granny flat exception). There is also, however, no equivalent in LBTT to the SDLT 2% surcharge for the purchase of residential property by non-residents.

The change was made by statutory instrument – The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Additional Amount: Transactions Relating to Second Homes etc.) (Scotland) Amendment Order, SSI 2022/375 – which was laid before the Scottish Parliament on Budget Day (15 December 2022) and came into force on 16 December 2022.

There is a limited transitional relief, in that the new 6% rate does not apply to transactions where a contract was entered into prior to 16 December 2022. As is usual for the transitional rules for LBTT and ADS rate changes, it does not matter if a pre-16 December contract is conditional, or if it is varied or assigned.

The impact of the ADS increase will be significant for many purchasers. The residential rates of LBTT are higher than those which apply in other parts of the UK, and the increase in ADS creates a further divergence. The total tax (LBTT and ADS) on a £250,000 second home in Scotland is now £17,100, compared to £7,500 on an equivalent property in England or Northern Ireland, and £12,450 for an equivalent property in Wales. For a £1,000,000 second home, the total tax in Scotland is now £138,350 compared to £71,250 in England or Northern Ireland and £101,200 in Wales.

In December 2021, the Scottish government launched a review of the ADS (The land and buildings transaction tax – additional dwelling supplement: a call for evidence and views). The main areas addressed in the consultation were:

The consultation closed on 11 March 2022, but the results have yet to be published. The Scottish government confirmed in the Budget that a response to the ADS consultation will be published early in 2023, together with a consultation on draft legislation.

Scottish landfill tax (SLfT) is a fully devolved Scottish tax which applies to the disposal of waste to landfill in Scotland. The standard rate of SLfT will increase to £102.10 per tonne and the lower rate of SLfT to £3.25 per tonne with effect from 1 April 2023, in line with UK landfill tax increases. Maintaining consistency with the UK rates is intended to avoid ‘waste tourism’, i.e. the moving of waste around the UK to take advantage of a lower tax charge on landfill in one part of the UK.

The Scotland Act 2016 provided for the devolution of aggregates levy to Scotland, but the process was delayed by longstanding litigation relating to the UK aggregates levy and by a review of the UK levy in 2020. The Scottish government is now working towards the introduction of a Scottish Aggregates Levy Bill and a consultation on the design of the new tax was held in 2022 entitled Breaking new ground? Developing a Scottish tax to replace the UK aggregates levy: consultation.

A key focus of the new tax is to support the circular economy, including recycling of aggregate, but devolution of the aggregates levy could involve particular issues for companies which operate on a UK wide basis. These include potential double taxation and other issues relating to the interaction between the UK and Scottish taxes. Although the Scottish government is keen to introduce a distinctive new tax, there could also be tensions if the rates of aggregates levy differ across the UK, or if the Scottish reliefs operate differently from those in the rest of the UK. The Scottish aggregates levy will be administered and collected by Revenue Scotland, and it will be important to ensure that sufficient sanctions are included in the new tax to ensure compliance. The provisional date for introducing the Scottish aggregates levy is 1 April 2025, and the UK aggregates levy will apply until that time.

Air departure tax (ADT) is the planned replacement for air passenger duty (APD) for passengers departing from Scottish airports. Legislation for the ADT has been passed (The Air Departure Tax (Scotland) Act 2017) but implementation has been delayed. A number of issues are still to be resolved, including how to retain in ADT the current exemption from APD which applies to flights departing from airports in the Highlands and Islands. The Scottish government is also considering the rates of ADT against its climate change objectives. The Scottish government remains committed to the introduction of ADT once solutions to these issues can be found.

The Scotland Act 2016 allows for half of VAT receipts attributable to Scotland (10p of the standard rate of VAT and 2.5p of the reduced rate) to be assigned to the Scottish government. VAT rates will continue to be set at a UK wide level. Arriving at the VAT attributable to Scotland to form the basis for assignment has proved to be extremely challenging: the figures cannot be extracted from VAT returns, and requiring separate ‘Scottish’ VAT returns to be submitted would be both unworkable and unwelcome. A model based on expenditure in Scotland has been jointly developed by the Scottish and UK governments, and is being used by the Scottish Fiscal Commission to forecast assigned VAT revenues.

VAT assignment was due to be introduced from April 2021, but due to the uncertainty caused by Covid-19 and EU exit, the UK and Scottish governments agreed to postpone implementation. The plans for VAT assignment are being considered as part of the current review of the Fiscal Framework. This is the agreement between the UK and Scottish governments which sets out how Scotland’s tax and social security powers are managed and implemented, and how funding for the Scottish Budget is adjusted following devolution of taxes and social security (the block grant adjustments).

The stability of the Scottish Budget appearing in its ‘normal’ timeslot was balanced by some fairly radical departures from UK tax policy. Until the leaks on Budget day itself, few would have predicted the 1p rise in the top two rates of Scottish income tax, although the replication (at least) of the reduction in the top rate threshold was a near-certainty. The 50% rise in the ADS rate was also a surprise; it will be interesting to see if this is a tax too far for at least some elements of the Scottish housing market. Those particular changes are perfect illustrations of the continuing opportunities and limitations on a partially devolved tax system – one going a little further in the direction of travel taken at Westminster where there is little scope for a completely different road; the other increasing very obviously the differences between the completely devolved LBTT and its SDLT forebear. The expectation must be that the tax roads will continue to diverge, as one approaches Berwick-on-Tweed.