The EU steps up its transfer pricing work with the Commission issuing two transfer pricing papers and investigating rulings given by member states. China is scrutinising transfer pricing for service fees in increasing detail using multiple audit tests. In the Americas, a recent Canadian ruling gives guidance on applying the arm’s length principle where functional adjustments are made, while Columbia tightens the scope of its transfer pricing rules. In Italy, domestic transfer pricing rules appear to be taking on a new significance to counter perceived tax abuses.

Martin Zetter provides an update on transfer pricing developments from around the globe

The European Union has launched a number of initiatives to challenge the dominance of the OECD in transfer pricing matters. The Commission’s decision to open investigations into decisions by the tax authorities of Ireland, Luxembourg and The Netherlands has been widely reported.

Beyond transfer pricing, state aid and member states’ autonomy in taxing rights are also at issue. Furthermore, the Commission’s June transfer pricing Communication sets out its stall for greater involvement in transfer pricing matters (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee, Brussels, 4.6.2014 COM(2014) 315 final).

Beyond transfer pricing, state aid and member states’ autonomy in taxing rights are also at issue. Furthermore, the Commission’s June transfer pricing Communication sets out its stall for greater involvement in transfer pricing matters (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee, Brussels, 4.6.2014 COM(2014) 315 final).

The European Commission issued a memo on transfer pricing at the same time (MEMO/14/394) which notes that the interpretation and application of the arm’s length principle in EU member states varies between tax administrations. It acknowledges that the uncertainty, costs and administrative burdens this creates impact negatively on business and the smooth functioning of the internal market.

The memo sets out the work the EU Joint Transfer Pricing Forum (EU JTPF) will complete in the coming months. The focus will be on the practical functioning of the Arbitration Convention and the revised Code of Conduct for the effective implementation of the Arbitration Convention. Proposals to improve the Code of Conduct covering transfer pricing documentation may be expected in due course.

In terms of audit work, the emphasis continues to be on moving towards increased cooperation between the tax authorities of member states. Cooperation between taxpayers and tax administrations to help identify areas of high and low risk is also stressed. Member states are recommended to break down audit work into three phases:

Best practice for tax authorities is also to carry out simultaneous audits of both sides of a transfer pricing case, as authorised under the Administrative Cooperation Directive (Council Directive 2011/16/EU of 15 February 2011 on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation), although this is yet to appear as a common feature in practice.

In my May briefing, I mentioned the member state transfer pricing profiles posted on the EU Joint Transfer Pricing Forum website.

The profile for France has now been added to the site. It contains links through to the French government website where the transfer pricing rules can be seen in summary.

Why it matters

The EU is shaping up to provide a regional transfer pricing arena. This may be helpful if it includes measures to relieve double taxation more effectively. However, insofar as it becomes more onerous than the OECD, post-BEPS, this will be unpopular with taxpayers and could put EU companies at a disadvantage.

China is increasingly challenging the transfer pricing of fees for intra-group services paid by local subsidiaries. The State Administration of Taxation (SAT) is now applying a number of audit tests to determine whether an adjustment should be imposed. A benefit test considers whether the Chinese company actually benefits from the services and asks whether, between independent parties, a recipient would purchase the same services because they are truly needed. The test is carried out from the perspective of both the provider and the buyer of the services. The transaction is then tested for duplication, value creation and remuneration, before facing an ‘authenticity’ test.

China is noteworthy in disallowing management fees per se (article 49 of the Corporate Income Tax Law Implementation Rules), so it is important that intra-group service charges are not made in respect of generalised activities. It is therefore essential to show that the charges made do not arise from the associated relationship, but represent specific services which would have been purchased externally had they not been provided by the group.

For example, if the HR function charges, at arm’s length, for parent company employees who train the Chinese subsidiary’s staff, there is likely to be an actual benefit. The SAT contrasts this with cases where the parent might benefit more from the services than the subsidiary; for example, in the case of charges made for strategic management activities. In practice, the group is likely to benefit from such activities as a whole and it is rather difficult to say how much the Chinese operations benefit, as distinct from the rest of the group. In any case, this is likely to vary over time. The SAT does not rule out a partial deduction in such cases, but it would be fair to say that the bar has been set high.

Of the various tests used, the authenticity test is probably the hardest to pin down. Of course, it is difficult to validate the authenticity of services provided to subsidiaries because large groups tend to have so many intra-group charges and the reasonableness of the allocation keys used is inevitably disputable. Nonetheless, the authenticity test does seem to be vague and subjective. It seems the SAT considers it seldom has the full picture across the group. One could be forgiven for thinking SAT officials will be looking to use country by country reporting, and other information exchange measures, to spot taxpayers using different transfer pricing methods or allocation keys between countries. Groups with such inconsistencies may well be advised to transition to a more aligned position as soon as possible.

Why it matters

Although China is not an OECD member, it follows the arm’s length principle and much of the OECD Guidelines in its transfer pricing law (article 41 of the Corporate Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China 2007). However, there are significant departures and some of these have been highlighted in the United Nation’s Practical manual on transfer pricing for developing countries, chapter 10.3, while others have featured in statements by SAT officials.

Among measures recently introduced by Columbia, the following points are typical of the way in which many countries have been tightening their transfer pricing rules. Transactions with permanent establishments are fully brought into the scope of transfer pricing, as are connected transactions made through a third party or a joint venture arrangement. The changes to the regulations, made in Decree 3030/2013, make a number of such modifications to the compass of economically linked positions under the transfer pricing rules (Law 1607 enacted in December 2012). Transactions involving the county’s tax free trading zones are also affected.

Due to the volatility of the Colombian peso, entry thresholds to the transfer pricing rules and the documentation requirements are measured by reference to ‘taxable units’; for example, equity capital of 100,000 taxable units, or gross income of 61,000 taxable units. However, the limits do not apply to transactions with tax havens which are caught separately, a feature we are seeing increasingly in other jurisdictions.

Intra-group financing is subject to a thin cap debt-to-equity ratio of 3:1 and a comparability analysis must support the interest deduction to avoid treatment as a deemed capital contribution with imputed dividends.

Why it matters: In common with other countries, this reflects a trend to broaden the scope of the transfer pricing rules and to limit the availability of safe harbours, or de minimus exemptions, to tax havens.

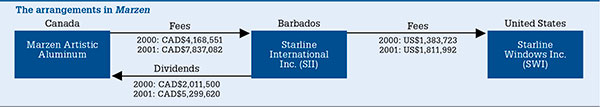

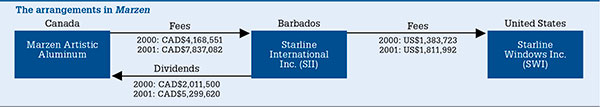

In a case before the Tax Court of Canada, Marzen, a Canadian taxpayer, paid fees to its Barbadian subsidiary SII for marketing and sales services in respect of its window products in the US (Marzen Artistic Aluminum Ltd v The Queen 2014 TCC 194). See the boxed figure below for details of the arrangements in this case.

The court found that the nature of the services differed from the description in the agreement and from what would have been provided between independent parties. The Canada Revenue Agency had disallowed a deduction to the extent of fees greater than the amounts SII had paid to another subsidiary, SWI, for staff to provide the services. The court disagreed with that level of disallowance, using the OECD guidelines and established law in three recent cases to consider the correct amount (Canada v GlaxoSmithKline 2012 SCC 52 (SCC); The Queen v General Electric Capital of Canada 2010 FCA 344 (FCA); and Alberta Printed Circuits Ltd v The Queen 2011 TCC 232 (TCC)).

Why it matters

This decision is important because it affirms that the arm’s length test is the correct way to determine an allowable fee. It also references three Canadian cases that give guidance on pricing at arm’s length and these cases may have persuasive authority in the UK and elsewhere. The whole fee is not disallowed merely because the services delivered do not exactly match those originally envisaged. Rather, it is the facts that dictate the price an independent party would have been prepared to pay and the deduction should be revised accordingly.

The question is often asked: do transfer pricing rules apply to transactions between parties in the same country? Many countries do have such rules. In the UK, these were recently revised to prevent the abusive use of compensating adjustments. Domestic transfer pricing rules have sometimes been described as ‘honoured in the breach’, but they are increasingly applied whenever a tax advantage is perceived to accrue. The Italian Corte di Cassazione recently applied the arm’s length principle between two connected parties in Italy to prevent a tax advantage (Decision No. 8849, 16 April 2014) and we may expect this trend to develop further.

On the BEPS front, the OECD hopes to issue proposals on intra-group financing transfer pricing later this year. Speaking at the Tax Journal’s recent BEPS event, Kate Ramm, OECD special adviser on BEPS, mentioned that OECD is currently working on the 2015 BEPS deliverables and a consultation on interest could be expected by the end of the year.

The EU steps up its transfer pricing work with the Commission issuing two transfer pricing papers and investigating rulings given by member states. China is scrutinising transfer pricing for service fees in increasing detail using multiple audit tests. In the Americas, a recent Canadian ruling gives guidance on applying the arm’s length principle where functional adjustments are made, while Columbia tightens the scope of its transfer pricing rules. In Italy, domestic transfer pricing rules appear to be taking on a new significance to counter perceived tax abuses.

Martin Zetter provides an update on transfer pricing developments from around the globe

The European Union has launched a number of initiatives to challenge the dominance of the OECD in transfer pricing matters. The Commission’s decision to open investigations into decisions by the tax authorities of Ireland, Luxembourg and The Netherlands has been widely reported.

Beyond transfer pricing, state aid and member states’ autonomy in taxing rights are also at issue. Furthermore, the Commission’s June transfer pricing Communication sets out its stall for greater involvement in transfer pricing matters (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee, Brussels, 4.6.2014 COM(2014) 315 final).

Beyond transfer pricing, state aid and member states’ autonomy in taxing rights are also at issue. Furthermore, the Commission’s June transfer pricing Communication sets out its stall for greater involvement in transfer pricing matters (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee, Brussels, 4.6.2014 COM(2014) 315 final).

The European Commission issued a memo on transfer pricing at the same time (MEMO/14/394) which notes that the interpretation and application of the arm’s length principle in EU member states varies between tax administrations. It acknowledges that the uncertainty, costs and administrative burdens this creates impact negatively on business and the smooth functioning of the internal market.

The memo sets out the work the EU Joint Transfer Pricing Forum (EU JTPF) will complete in the coming months. The focus will be on the practical functioning of the Arbitration Convention and the revised Code of Conduct for the effective implementation of the Arbitration Convention. Proposals to improve the Code of Conduct covering transfer pricing documentation may be expected in due course.

In terms of audit work, the emphasis continues to be on moving towards increased cooperation between the tax authorities of member states. Cooperation between taxpayers and tax administrations to help identify areas of high and low risk is also stressed. Member states are recommended to break down audit work into three phases:

Best practice for tax authorities is also to carry out simultaneous audits of both sides of a transfer pricing case, as authorised under the Administrative Cooperation Directive (Council Directive 2011/16/EU of 15 February 2011 on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation), although this is yet to appear as a common feature in practice.

In my May briefing, I mentioned the member state transfer pricing profiles posted on the EU Joint Transfer Pricing Forum website.

The profile for France has now been added to the site. It contains links through to the French government website where the transfer pricing rules can be seen in summary.

Why it matters

The EU is shaping up to provide a regional transfer pricing arena. This may be helpful if it includes measures to relieve double taxation more effectively. However, insofar as it becomes more onerous than the OECD, post-BEPS, this will be unpopular with taxpayers and could put EU companies at a disadvantage.

China is increasingly challenging the transfer pricing of fees for intra-group services paid by local subsidiaries. The State Administration of Taxation (SAT) is now applying a number of audit tests to determine whether an adjustment should be imposed. A benefit test considers whether the Chinese company actually benefits from the services and asks whether, between independent parties, a recipient would purchase the same services because they are truly needed. The test is carried out from the perspective of both the provider and the buyer of the services. The transaction is then tested for duplication, value creation and remuneration, before facing an ‘authenticity’ test.

China is noteworthy in disallowing management fees per se (article 49 of the Corporate Income Tax Law Implementation Rules), so it is important that intra-group service charges are not made in respect of generalised activities. It is therefore essential to show that the charges made do not arise from the associated relationship, but represent specific services which would have been purchased externally had they not been provided by the group.

For example, if the HR function charges, at arm’s length, for parent company employees who train the Chinese subsidiary’s staff, there is likely to be an actual benefit. The SAT contrasts this with cases where the parent might benefit more from the services than the subsidiary; for example, in the case of charges made for strategic management activities. In practice, the group is likely to benefit from such activities as a whole and it is rather difficult to say how much the Chinese operations benefit, as distinct from the rest of the group. In any case, this is likely to vary over time. The SAT does not rule out a partial deduction in such cases, but it would be fair to say that the bar has been set high.

Of the various tests used, the authenticity test is probably the hardest to pin down. Of course, it is difficult to validate the authenticity of services provided to subsidiaries because large groups tend to have so many intra-group charges and the reasonableness of the allocation keys used is inevitably disputable. Nonetheless, the authenticity test does seem to be vague and subjective. It seems the SAT considers it seldom has the full picture across the group. One could be forgiven for thinking SAT officials will be looking to use country by country reporting, and other information exchange measures, to spot taxpayers using different transfer pricing methods or allocation keys between countries. Groups with such inconsistencies may well be advised to transition to a more aligned position as soon as possible.

Why it matters

Although China is not an OECD member, it follows the arm’s length principle and much of the OECD Guidelines in its transfer pricing law (article 41 of the Corporate Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China 2007). However, there are significant departures and some of these have been highlighted in the United Nation’s Practical manual on transfer pricing for developing countries, chapter 10.3, while others have featured in statements by SAT officials.

Among measures recently introduced by Columbia, the following points are typical of the way in which many countries have been tightening their transfer pricing rules. Transactions with permanent establishments are fully brought into the scope of transfer pricing, as are connected transactions made through a third party or a joint venture arrangement. The changes to the regulations, made in Decree 3030/2013, make a number of such modifications to the compass of economically linked positions under the transfer pricing rules (Law 1607 enacted in December 2012). Transactions involving the county’s tax free trading zones are also affected.

Due to the volatility of the Colombian peso, entry thresholds to the transfer pricing rules and the documentation requirements are measured by reference to ‘taxable units’; for example, equity capital of 100,000 taxable units, or gross income of 61,000 taxable units. However, the limits do not apply to transactions with tax havens which are caught separately, a feature we are seeing increasingly in other jurisdictions.

Intra-group financing is subject to a thin cap debt-to-equity ratio of 3:1 and a comparability analysis must support the interest deduction to avoid treatment as a deemed capital contribution with imputed dividends.

Why it matters: In common with other countries, this reflects a trend to broaden the scope of the transfer pricing rules and to limit the availability of safe harbours, or de minimus exemptions, to tax havens.

In a case before the Tax Court of Canada, Marzen, a Canadian taxpayer, paid fees to its Barbadian subsidiary SII for marketing and sales services in respect of its window products in the US (Marzen Artistic Aluminum Ltd v The Queen 2014 TCC 194). See the boxed figure below for details of the arrangements in this case.

The court found that the nature of the services differed from the description in the agreement and from what would have been provided between independent parties. The Canada Revenue Agency had disallowed a deduction to the extent of fees greater than the amounts SII had paid to another subsidiary, SWI, for staff to provide the services. The court disagreed with that level of disallowance, using the OECD guidelines and established law in three recent cases to consider the correct amount (Canada v GlaxoSmithKline 2012 SCC 52 (SCC); The Queen v General Electric Capital of Canada 2010 FCA 344 (FCA); and Alberta Printed Circuits Ltd v The Queen 2011 TCC 232 (TCC)).

Why it matters

This decision is important because it affirms that the arm’s length test is the correct way to determine an allowable fee. It also references three Canadian cases that give guidance on pricing at arm’s length and these cases may have persuasive authority in the UK and elsewhere. The whole fee is not disallowed merely because the services delivered do not exactly match those originally envisaged. Rather, it is the facts that dictate the price an independent party would have been prepared to pay and the deduction should be revised accordingly.

The question is often asked: do transfer pricing rules apply to transactions between parties in the same country? Many countries do have such rules. In the UK, these were recently revised to prevent the abusive use of compensating adjustments. Domestic transfer pricing rules have sometimes been described as ‘honoured in the breach’, but they are increasingly applied whenever a tax advantage is perceived to accrue. The Italian Corte di Cassazione recently applied the arm’s length principle between two connected parties in Italy to prevent a tax advantage (Decision No. 8849, 16 April 2014) and we may expect this trend to develop further.

On the BEPS front, the OECD hopes to issue proposals on intra-group financing transfer pricing later this year. Speaking at the Tax Journal’s recent BEPS event, Kate Ramm, OECD special adviser on BEPS, mentioned that OECD is currently working on the 2015 BEPS deliverables and a consultation on interest could be expected by the end of the year.